Azov fighter Yaroslav Kozyriev’s Mother, “I Reached a Point Where I Didn’t Understand Why I Had to Get out of Bed.” The Story of Captivity

“My mornings begin with a prayer to God, asking Him to strengthen my son, protect him from evil people and torture. And that’s the last thing I think about before falling asleep,” Iryna Kozyrieva, mother of an Azov Brigade soldier, says through tears. Her son Yaroslav has been held in Russian captivity for 29 months. However, under the Geneva Conventions, he should have been exchanged two years ago.

Iryna Kozyrieva has raised six foster sons. “If I had to go through it all over again, I might not have taken the risk. I love all my sons, but it was a challenging path,” the woman admits sincerely.

She worked as a child psychologist at a Children’s Social Rehabilitation Center. She joined the Centre as a young specialist, and it was to her that they would send the children with the worst behavior, who no one else could handle. The boys and girls at the Center were taught, developed, and fed, but the teachers couldn’t replace their parents.

Iryna Kozyrieva, mother of Azov fighter Yaroslav Kozyriev

— No matter how good the system is, a child needs to be attached to someone and feel that someone loves them. That’s how my children gradually, one or two, ended up with me. My grandmother used to say, “Irochka, how are you not afraid of them? They’re bandits!” But back then, I wasn’t afraid of anything at all. I felt like the conductor of a great orchestra: one wave of the hand—and the music begins, the woman recalls.

When Iryna had raised her four older sons, two more boys joined her large family—siblings Yaroslav and Robert.

They were young: Yaroslav was 9, and Robert was 7. I often stayed late at work, and they would call me to them, “Come here, the kids are sobbing bitterly.” I would go, put my hand on their heads, and we would talk. But then it was hard to go home and leave them there —Iryna recounts.

From the way she talks, you would never guess that all of her children are adopted. Iryna calls them ‘my sonnies’ and talks about each of them with great tenderness. Today, her heart is aching the most for the younger children. Yaroslav has been in enemy captivity for more than two years, and Robert went off to defend the country after hearing the news about his brother’s capture.

A childhood photo of Yaroslav (right) and Robert (left). Photo: family archive

Azovstal

—When Yaroslav was 14 and Robert was 12, the Maidan began. Students were beaten in Kyiv. I was going to a rally, and they told me, “We’re coming with you.” I told them kids shouldn’t go there; it was too dangerous. And they replied, “Well, if kids can’t go, then women shouldn’t go either.” So I had to take them with me — Iryna smiles. —They put on football gear—knee pads, elbow pads, helmets, and wrapped scarves around themselves. They were going to Maidan to protect their mom and the students. They have been like that since childhood, especially Yaroslav. He has always fought for justice. And that’s how he ended up in the most dangerous place in Ukraine at the most dangerous time, — the woman sighs.

Yaroslav Kozyriev signed a contract with the Azov Brigade before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. He didn’t tell his mom about it to spare her unnecessary worry. His older brother informed Iryna of his decision. At that point, Yaroslav was already in eastern Ukraine, so the woman had to accept his choice.

Iryna Kozyrieva with her son Yaroslav before the full-scale invasion. Photo: family archive

—Inside, I wanted to scream and cry because I realized these were not just soldiers; they were Azov. They were the ones ready to die for their beliefs. And Yaroslav felt like a fish in water with them. He wanted me to be proud of him. And I couldn’t help but be proud, —Iryna continues.

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the Azov fighters defended Mariupol, and Yaroslav was among them. In March 2022, he was wounded and ended up in ‘Zaliziaka’—a medical hospital located in one of the Azovstal bunkers. From there, the young man sent messages to Iryna.

—He prepared me for the fact that they had no way out. He texted they had no ammunition or means to defend themselves. He told me where he wanted to be buried and made me promise. We both apologized for everything. He was saying goodbye, telling me he wouldn’t go into captivity. He said he would face the enemy with a weapon, and they would shoot him—the woman recalls with sadly.

However, in mid-May 2022, the President of Ukraine ordered the lives of the military personnel who remained at Azovstal to be preserved. This was called an evacuation, the so-called ‘honorable captivity.’ On 16 May 2022, the severely wounded left the metallurgical plant, and most of them were transported to a hospital in occupied Novoazovsk.

Yaroslav Kozyriev at Azovstal. Photo: family archive

Yaroslav Kozyriev ended up in captivity on 18 May. The day before, he called his mother to bid farewell again, informing her he would destroy his phone and wouldn’t get in touch for three months. The Azov fighters hoped they would be exchanged within 3 to 4 months. Along with other defenders of Mariupol, Yaroslav was transported to Volnovakha Colony No. 120 in the village of Olenivka, the Donetsk region. The captivity was supposed to be a salvation for the Ukrainian soldiers. However, it turned into another circle of hell for them and their families.

Olenivka

Ukrainian soldiers who have endured Russian captivity recount many horrifying experiences. The brutal treatment by guards in colonies, detention centers, and prisons can sometimes lead to the deaths of military personnel in captivity. The Media Initiative for Human Rights is aware of many such stories. The most significant mass murder of Ukrainian captives occurred in Volnovakha Colony on the night of 28 to 29 July 2022.

Two and a half months after the defenders of Mariupol left Azovstal, the Russian media reported that several explosions had occurred in the penal colony in Olenivka, leading to a fire in one of the barracks. Information about casualties spread through social media; propagandists released the first lists of names. Iryna Kozyrieva learned about the tragedy from Yaroslav’s girlfriend.

On 29 July, she sent me a piece of the list. Before I could even look at it, she started calling, crying over the phone, and screaming, “He’s on the list! He’s dead!” I looked at the list and said, “This can’t be happening!” That was my first reaction. My brain couldn’t accept anything else. I told her to send me the top of the list. She sent it, and I saw that at the top it said ‘deceased,’ but in the second part, where my Yaroslav’s last name and date of birth were listed, it said ‘list of the wounded’ — the woman recounts.

At first, Iryna felt relieved, but then the news came that one captive had died on the way to the hospital. The MIHR is aware that after the fire in the Olenivka colony, at least nine Ukrainian soldiers perished due to the inaction of the administration. In total, 50 prisoners of war died that night and the following day, with another 130 wounded—all of them from the Azov Brigade.

Iryna’s son, Yaroslav, was also severely wounded. She found out he was alive when she saw him in one of the Russian news reports.

— In that video, he was sitting half-turned by the window. I recognized him by his profile. Later, the exchanged soldiers reported that they weren’t actually treated. They were just bandaged with some rags. They said his arm hadn’t healed; he couldn’t move it, couldn’t raise or lower it. There were also some shrapnel wounds, but they weren’t seen in the video —Iryna says.

Yaroslav Kozyriev in hospital after being wounded in Olenivka colony. Photo: screenshot from a Russian media report

Since that day, the families of Azov soldiers have had limited information about their captured relatives. Responding to a call from the Red Cross, Iryna wrote letters to her son but never received any replies.

—I have a lawyer both in Ukraine and Russia. At the request of my Russian lawyer, I received a letter from the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation stating that my son was being held in the Russian Federation and his health was satisfactory. It was on 28 February this year. I was so happy. I thought that they would not write that about a dead man. I know he was in Taganrog, but I don’t know where he is now. There is no information—Iryna explains.

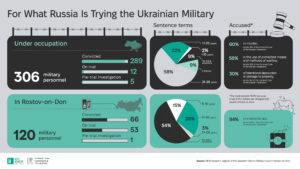

Iryna notes that many of the Azov captives have been convicted by Russia on trumped-up charges. After these show trials, families receive information about prisoner’s whereabouts and can correspond with them.

—They are given ridiculous sentences for defending their homeland—25, 27, 28 years, or even life imprisonment. But after conviction, they can at least correspond with their families. We are denied that possibility. No institution acknowledges that they hold our relatives until they are convicted — Iryna explains.

The Struggle

The news of her son being wounded in Olenivka dealt a heavy blow to the mother’s mental state.

—If you think it’s easier for me because my children are adopted, that’s not true at all, — Iryna emphasizes.

In her mind, she relives the attack over and over, as if she were actually there, even though she wasn’t physically present.

—When I think about those days—those burned bodies, that blood… those images haunted me for a long time. During the day, while working, it seems okay, but when I go to bed, all I can see are explosions, everything burning, the smell of blood, smoke, and screams. Living with this is incredibly hard. I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Then I reached a point where I didn’t even understand why I should get out of bed, what sense of it all, — the woman shares.

Iryna found the strength only to participate in rallies supporting prisoners of war and share the story of Yaroslav’s captivity. Each time she attended a rally, she cried, and afterward, she would spend several days at home with high blood pressure.

A recreational and therapeutic camp for wives and mothers of prisoners of war and those killed in captivity helped her to get out of apathy and complete despair. The camp was held in the Carpathians, where psychologists worked with the women the entire time.

The recreational and therapeutic camp for wives and mothers of prisoners of war and those killed in captivity. Photo: Suspilne

—It was very professional support. We could openly grieve among others who were just as exhausted as us. Everyone around us was tired of our sorrow, and suddenly, we found ourselves among people like us. It was an incredible journey. I quickly moved from a horizontal position to a vertical one —Iryna shares.

She returned from the retreat full of energy to fight. She even adopted a dog, as Yaroslav had always dreamed of.

Her job also helps her cope with stress: she continues to work as a child psychologist. She explains:

— Children provide a definite resource because they are our future. That’s why I work and help as much as I can. I feel joy to know that I am helpful to my homeland and society.

Iryna also feels significant support from the Olenivka Community. This is a non-governmental organization that united the families of those killed and wounded during the crime in Olenivka colony. Their shared grief motivates the families to act together, as it makes it easier for officials to agree to meetings, and their collective voice becomes more powerful.

—In the community, there are various people. I find it rewarding to help someone, to write a statement for someone, or to send a document somewhere. We can support each other, help one another, and offer advice. If someone has information, we share it — Iryna Kozyrieva remarks.

Iryna Kozyrieva (in the center) holds a poster with a photograph of her son at a rally to remind others about prisoners of war

In addition, the woman believes that it was their joint efforts that achieved what seemed impossible: they compelled law enforcement to investigate the wounding of their relatives in the Olenivka colony as a war crime.

—The thing is that the criminal case of those killed in Olenivka was investigated by the SSU. Meanwhile, the cases of the wounded were scattered throughout Ukraine and considered under Article 115 of the Criminal Code, which pertains to premeditated murder. But that’s immoral! We were told it didn’t matter and it was the best article for us. But we disagreed. It took a tremendous effort to prove that the wounding in Olenivka was also a war crime — Iryna recalls.

As a result, the cases of the deceased and wounded in the Volnovakha colony have been consolidated. They are currently being considered under Article 438 of the Criminal Code, which pertains to violations of the laws and customs of war. For information on the ongoing investigation and the main lines of inquiry being considered by the prosecution, read the article prepared by the MIHR commemorating the anniversary of the tragedy in Olenivka.