Human rights defenders prove Russia tortures Ukrainian soldiers just like the USSR once did

The Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) has presented a new analytical report comparing the torture methods used by modern-day Russia against Ukrainian prisoners of war with Soviet-era practices. The report’s authors demonstrate not only the continuity in the use of certain torture techniques but also the political motives behind them.

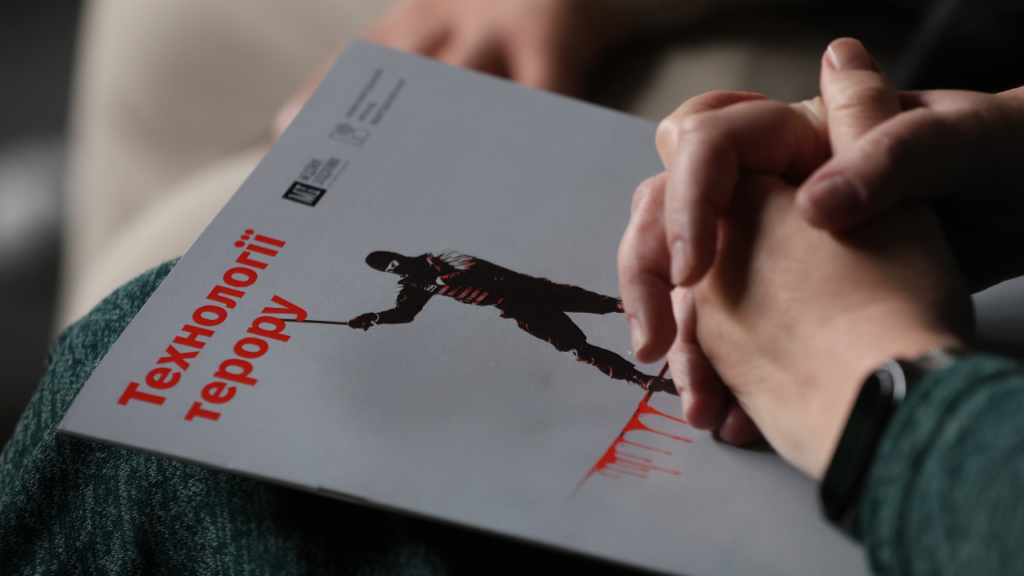

From 2022 to 2025, MIHR documented testimonies from 138 Ukrainian soldiers released from Russian captivity. Forty of those accounts formed the basis of the analysis “Technologies of Terror: A Comparative Analysis of Soviet and Russian Torture Methods.” According to MIHR documentarian Mariia Klymyk, identical torture techniques are used against Ukrainians at every stage of captivity and in all places of detention—both military and civilian.

“Russia violates all norms of international humanitarian law: they torture, use electric shock devices, deny medical care, food, outdoor time, and hygiene products to prisoners. All of this is done deliberately,” said Klymyk. “That’s why, in this report, we aimed to show all stages of captivity that Ukrainians endure and the methods of torture used at each stage. The world must understand what Russian captivity really is and pay attention. Silence legitimizes these crimes.”

Mariia Klymyk, MIHR documentarian. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

One of the cruelest procedures is “intake”—the first contact with the administration of a detention center or penal colony. It is carried out every time a prisoner is transferred to a new location. According to Mariia Klymyk, a person can undergo up to 12 such procedures during captivity. Intake includes brutal beatings, humiliation, and being attacked by dogs. It can last for hours. MIHR has previously described this practice in detail in this video.

At the presentation, former POW Ivan Dibrova from the 1st Mechanized Brigade shared that he witnessed the death of a fellow Ukrainian prisoner during an intake procedure. Ivan himself went through intake three times. The worst torture he experienced was upon arrival at the pre-trial detention center in Vyazma, Smolensk region, Russia. He was targeted for a tattoo of wings on his chest—a symbol of freedom. According to Ivan, the head of the detention center, a man named Zakharov, was present during the abuse:

“A rubber baton blow to the foot knocked me down. A Russian officer stepped on my head with his size 45 boot, smashing me into the tiles. Others electroshocked me in the neck, genitals, and legs while also beating me with batons. I lost consciousness at least three times. Then they threw me under a cold shower, which felt scalding hot to me. A Russian soldier electroshocked the water so that the current passed through my entire body.”

— Ivan Dibrova, former POW. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

The use of electric shock as a method of torture was widespread during Soviet times as well, said MIHR analyst Vladyslav Havrylov. One method, known as “tapik”, involved connecting wires from a TA-57 military field phone to the body and using it as an electroshock device.

For the comparative analysis, MIHR studied Soviet-era criminal case files from the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). According to Vladyslav Havrylov, the most significant finding was the continuity not just in the torture methods, but in the political logic behind them:

“The USSR fabricated criminal cases against political prisoners. They were tortured into confessing to crimes they didn’t commit. Today, Russia does the same with Ukrainian POWs. They are convicted of ‘terrorism’ after being forced under torture to confess to crimes they didn’t commit—even though their participation in war is protected under international law. It is their duty to defend their country.”

— Vladyslav Havrylov, MIHR analyst. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

Through this analysis, MIHR experts once again concluded that the cruel treatment of Ukrainian POWs and civilian detainees constitutes a crime against humanity. According to Anna Rassmakhina, head of MIHR’s Department of War and Justice, although it may currently be impossible to prosecute all perpetrators, it is crucial that the crimes themselves are thoroughly documented and legally qualified.

Read the full report here or view below.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.