280 days as a hostage: the ordeal of Olha Cherniak from Kherson, who endured torture and Russian captivity without breaking

Before the full-scale war erupted, Olha Cherniak was living in Kherson with her husband and children. They didn’t immediately leave after the city’s occupation, as they were caring for their sick parents. However, when they finally dared to leave, Olha, her husband Ihor, and son Stepan were captured by Russians. In captivity, Olha faced months of severe hardship under Russian control but managed to survive and eventually gained her freedom.

The abduction

The incident occurred on August 10, 2022, just a few days before they planned to evacuate. Olha traveled to Simferopol to deliver medical test results to her mother-in-law, who has cancer. However, she ran into trouble at the Armyansk-Kalanchak checkpoint, the administrative border with occupied Crimea. There, Olha presented her Ukrainian ID card as a passport to the Russian officials, who didn’t recognize it. Moreover, they denied her Ukrainian citizenship, claiming she was a Russian citizen. They referred to either a decree or a resolution, which purportedly stated that “everyone born in Crimea automatically becomes a Russian citizen.” Olha indeed was born on the peninsula, and her mother is a native Crimean. The family had lived in Crimea before being forced to relocate to Kherson Region.

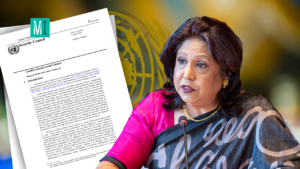

Olha Cherniak before captivity

In the end, Olha was allowed entry, but upon her return, their apartment was forcibly entered and searched by the occupiers. This incident happened late on the evening of August 11, when Olha, her husband Ihor, and their 19-year-old son were at home. The Russian forces, without any formal introduction, documentation, or explanation for the search, barged in.

Olha recounted the event, “There was a knock on the door, I looked and realized that we had unwelcome guests. Given that my husband’s workplace had already been searched, we anticipated a visit to our home, but never imagined we would be abducted.”

“About eight to ten individuals entered, with two wearing black uniforms. They frisked me for weapons, while I was wearing a light home dress. They pushed me against the wall and order me to place my hands behind my head and spread my legs as wide as possible, ordering me to drop any weapons.”

The Russians conducted a thorough search of the apartment, intimidating Olha throughout the process. While her son and husband were confined to a room, Olha was kept in the corridor, instructed to stand still with her head down, under threat of being shot in the head. The search yielded her passport and ID card. Valuables, including two computers, two laptops, five cell phones, garage and car keys, and savings meant for Ihor Cherniak’s mother’s treatment, were seized.

The family was then removed from their home, loaded into a vehicle, and taken to the Kherson pretrial detention center on Teploenergetykiv Street. Ihor and Stepan were placed into small cells known as “glasses”, offering only sitting space.

A confusion arose over Cherniak’s two passports – one in her maiden name and the other in her married name. The couple had married recently after 12 years together, and Olha hadn’t updated her documents. Without anyone reasonable to explain the situation to, Olha’s wedding ring was taken, a smelly hat was pulled over her head to blind her, and she was placed in a two-bunk cell already housing five women: three on the floor and two on the bed. Olha was given only a blanket and two books to use as a pillow.

Kherson pretrial detention center on Teploenergetykiv Street. Photo courtesy of Human Rights Watch

Cherniak informed the occupiers that her mother-in-law was ill and required her medicine to be taken to the hospital. After some consideration, they assigned an escort to Olha and permitted her to return to Simferopol. Olha recalls a notable incident from that journey: her escort was unfamiliar with elevators.

“I went over and pressed the button, and he said: ‘Why did you press it?’ I replied: ‘For the elevator to come to the first floor.’ We go inside, I push the button for the third floor, and this Russian guy is standing there scared. The man did not understand what those buttons were for and what an elevator was and how to use it. And these people came to ‘liberate’ us.”

The return to the pretrial detention center

Upon their return to Kherson, life for Olha and her family became extremely difficult. The Russians indicated they would start the interrogation with her son, then proceed to Olha. She was escorted down a corridor. This time they kept the hat off on purpose, so Olha would be forced to witness her son being harshly escorted, a tactic used to intimidate her. He was bent down to the floor, held by the neck. Olha was then taken to the second floor, and 10 to 15 minutes afterwards, brought downstairs to a corridor where she could hear her son being interrogated. He was subjected to electric shocks, leading him to falsely incriminate himself and his family. At the time he was 19 years old:

“He is just a child. He had never witnessed any cruelty or violence before. Even adult men are broken there. I don’t blame him, he did the right thing. They told him to blame me for everything, because they needed me,” recalls Olha Cherniak.

After the torture, the boy was taken out into the corridor to talk to his mother. Then the Russians began to torture Olha: they took her to the same room, attached so-called “crocodiles” to her fingers and started to electrocute her.

“I was electrocuted, I lost consciousness,” Olha recalls. “Then they would stop, I would come to, and they would continue. I was even saying goodbye to my life, but I realized that if I said that I was passing on the data, I would be prosecuted, and they would take me to Crimea and convict me. There are a lot of our people there who were taken illegally.”

Do you speak Ukrainian? Here’s a shock of current so you know better

During the interrogations, Olha tried to maintain eye contact with her torturers. They tried to intimidate her by claiming that her trip to Crimea had led to Ukrainian Armed Forces attacking Russian military targets, accusing her of providing coordinates for these attacks.

When Olha Cherniak responded in Ukrainian to the Russians, she was immediately subjected to electric shock. Following another interrogation session, Olha nearly lost her life:

“That time, they only electrocuted me. My fingers, burned by the electric shocks, turned black and blue. When I returned to the cell on the second floor and sat down, the ladies began asking me how I felt. However, I could not say anything, I just kept silent. Lilya (a cell mate – MIHR) said that I was white and had blue lips. Then I lost consciousness and fell down.

Her cell mates, witnessing her critical condition, banged on the door to alert the guards. At that time, among those detained was a man, a first responder by profession and a chiropractor before his capture. His identity remains undisclosed for safety reasons. This fellow captive played a crucial role in reviving Olha.

Olha Cherniak shares a photograph of herself post-captivity. Photo by Yevheniy Semeniuk for Sestry publication

“He was our guardian angel; he tried to revive all the prisoners after torture and administered first aid. Then my entire left side failed: the Russians messed up my heart rhythm with the current, causing a heart attack. Initially, he gave me some medicine, then applied oils, pinched my arm and leg, checking if I could feel anything.”

According to Olha Cherniak, this man was held by the Russians in a basement for 60 days, enduring torture, evident from the handcuff marks on his wrists. The occupiers stated that he would remain there until the capture of another doctor.

During her interrogations, Olha recounts that her torturers spoke about the sexual abuse of men at the Teploenergetykiv detention center, a heinous act reportedly committed by Kadyrov’s forces and recorded on their phones, according to her fellow prisoners.

On August 14, 2022, the occupiers coerced Olha into writing self-incriminating statements. Prior to this, she was electrocuted and threatened they would break her son’s limbs. The following day, her coerced confession was set to be recorded on a phone. However, her explanations did not satisfy the captors, who then blindfolded her:

“They told me they would take me to Donetsk, where I’d be imprisoned for ten years, and my husband and son would be shot, leaving it on my conscience. Then they came out and told me to go to the cell wearing a mask, saying everyone in Donetsk wears one. I went and hit my head on the wall. I asked them where to go, and they told me I had to find my own way out, laughing. Then I ran into the closet, tried to calm down, and began to remember where I had come from. I moved slowly towards the door with wide steps, and the floor was slightly visible from under the mask. That’s how I reached my cell. When climbing the stairs, they didn’t allow me to hold the railing. They discussed among themselves when they would take me to Donetsk. One said at the end of the month. My cell number was 21. When I got there, they forbade me to sleep, walk, receive parcels, or call a doctor.”

Olha describes the mass torture of prisoners when explosions rocked the city, with relentless screams echoing day and night. She recalls the arrival of ATO fighters at the Kherson pretrial detention center, who were tortured in the yard. The Russians attempted to drown out their screams with loud music, but the victims’ screams were too piercing to be masked.

“There were many deaths,” Cherniak adds, “I also heard that people were thrown into the trash. They mentioned that those detained for drunkenness or drugs were held for a day and released, but they dug graves behind the factory and took the tortured people there.”

Seven months without daylight and fresh air

In October 2022, as the Russians retreated from Kherson, they relocated their prisoners, including Olha, to Novotroitske village. She was confined in a police station cell there for seven months until her release.

“It was unbearably stuffy and hot, just impossible to endure. There was no fresh air, no sunlight; we saw nothing. We were locked in this room for seven months without going out for a walk. We were sitting there under only a light bulb, like in an incubator. Because of this, we now have problems with our eyesight, backs, knees, and our teeth have turned brown. We were sitting or lying down all the time, and our muscles started to atrophy.”

Olha Cherniak was unexpectedly released from Russian captivity on May 17, 2023. Prior to her release, the Russians questioned her about her attitude towards Russia and pressured her to accept Russian citizenship, which she refused. She was forced to sign a statement denying any complaints and was returned her wedding ring and passports, but not her phone. Her son was released after 15 days of detention, while her husband, also subjected to torture, was held for 30 days. In total, Olha spent 280 days in captivity.

Polina Dobrozhanska, journalist