A year of silence: who is responsible for the downing of the IL-76 over Belgorod — investigation

A year ago, on January 24, 2024, an IL-76 heavy military transport aircraft crashed in the sky over the Belgorod region. Russia claimed that Ukraine shot down a plane with 65 of its prisoners of war (POWs). Ukraine responded in general terms: military targets are legitimate targets.

For a year, the Media Initiative for Human Rights conducted its investigation into the circumstances of the downing, trying to find out the circumstances of the flight and the attack on the plane. During this time, we faced incredible difficulties. This is because it is difficult to investigate a crime in enemy territory, and most of those involved prefer to remain silent for a long time. In the end, we interviewed about four dozen witnesses and experts, used our sources in the Defense Forces, and restored the chronology of that day and the subsequent events. At the moment, we are not naming any specific people responsible, and we still cannot say that the downed IL-76 with the tail number RA-78830 was carrying Ukrainian prisoners of war. We are attempting to record the facts we have gathered.

DNA matches

— “I received a call from an investigator. There is a DNA match on my son,” — this short message was sent to the MIHR by the mother of Roman, a POW, on New Year’s Eve.

We met her the day before in Odesa. Like us, she has been trying to find out what happened on January 24, 2024, for a year. Everything she knows is based on rumors and speculation, and she has no official information.

— “When the full-scale invasion began, my son was 23. After conscript service, he signed a contract, served in the navy, and on February 24, 2022, he was in Skadovsk, Kherson region.”

She recalls a phone call from her son, who told her that on the first day of the full-scale invasion, their convoy was heading towards Mykolaiv:

— “But on the Antonivskyi bridge, the convoy was shot, and the soldiers ran away. My son called and shouted: “Mom, they are shooting us!” I heard explosions next to him. I heard him again in the evening: he asked me to call the commander to tell him he was alive.”

That’s how Roman and a few other guys ended up in the occupied territory. They changed into civilian clothes. At first, they hid on a farm and then dispersed to houses near Skadovsk. Roman regularly sent voice messages to his mother.

His mother plays one of them. The voice of a very young boy is heard: “I’m for Ukraine. I’m not a deserter. Initially, this task was to remove the uniform, and we explained it fifty times. We were the last column to leave Heroson. We didn’t make it in time and returned to the forest, where we were defeated. I keep in touch with my senior officer. I have conscripts with me; they cannot fight and do not know how to shoot. I signed a contract, and it’s my responsibility.”

— “On Easter night, April 24-25, Roman did not get in touch. It turned out that the boys from this military unit had been captured on April 14, and the guys from his unit were detained one by one and placed in a camp near Skadovsk. Eventually, all of them were detained. Roman was one of the last,” Roman`s mother says.

They took them to Nova Kakhovka, then to the occupied Crimea, and then to Sevastopol. According to his mother, an exchange occurred, but only conscripts from the unit were returned. Roman and several other guys were taken to Russia. They were placed in CF (Correctional Facility) no. 9 in Borysoglebsk, Voronezh region, and later transferred to CF no. 7 in Pakino, Vladimir region.

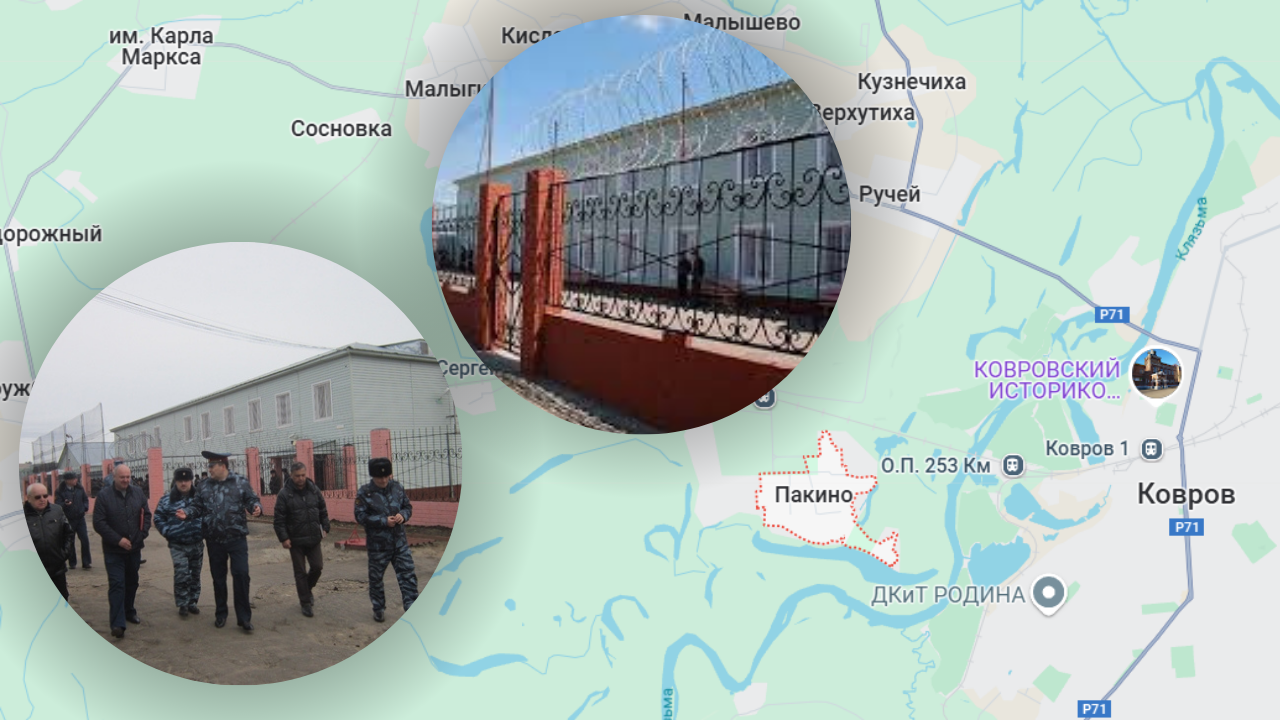

Correctional colony in Pakino, Vladimir region

— “I knew from the released prisoners that Roman was in Pakino, in captivity. That was enough for me. I didn’t want to bother any of the guys by asking for more. I also received a confirmation from the International Committee of the Red Cross,” adds the mother of a POW.

Instead, she regularly went to the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War (CH).

— “Once every two or three months, I would come to Kyiv, go to the CH, catch someone, and remind them of myself,” the woman continues, “I had a train ticket for January 23. At about 8 pm, I received a call from my son’s military unit and was told: “Congratulations, your son will be in Ukraine tomorrow.” I answered that I had to go to Kyiv. They did not refuse me. They just asked me not to discuss the exchange. On the morning of January 24, I went to the CH. There, I met a woman with whom I had talked earlier. She said: “You came at such a bad time, everyone went for the exchange.” I asked if my son was there. She said she didn’t know because not everyone had been informed about the exchange.

She made me coffee, and somewhere around 10:00, maybe a little later, they started saying that an IL-76 plane had been shot down. Later, they added that it was with our prisoners. They said they didn’t believe it themselves. And then they threw away the list of names. I said, let me see it. I saw my son’s name. I was numb: no tears, nothing. I’m sitting in the Korshtaib. Everything happened before my eyes. And they know more than they say.

On November 8, 2024, the bodies of 563 fallen Ukrainian defenders were returned to Ukraine. Among them were 62 people who could have been on board the IL-76 aircraft shot down in the Russian Federation in the Belgorod region on January 24, 2024. The Russians transferred three bodies to occupied Mariupol, claiming that the relatives of the victims were there.

In early January 2025, investigators reported that more than fifty bodies had DNA matches, while the remaining six had not yet been identified.

“Mode of silence”

On January 23, 2024, Kharkiv, which is located 30 kilometers from the border with Russia, was shelled three times by enemy troops. In the morning, a massive missile attack, including the use of S-300 anti-aircraft systems, killed 11 Kharkiv residents and injured more than 75. The Russians also damaged residential buildings and other civilian infrastructure. On January 25, the city declared a day of mourning.

The aftermath of the shelling of Kharkiv on January 23, 2024. Photo: National Police of Kharkiv region

The S-300 system is designed to engage strategic and tactical aircraft, tactical and operational ballistic missiles, and hypersonic targets. In other words, it is a universal air defense system for the protection of essential facilities or for covering ground troops. During the full-scale invasion, the Russians modified it and used it en masse to strike ground targets. The trajectory of the missiles is ballistic, the projectile travels at high speed, and Ukrainian air defense is powerless. The only way to defend ourselves is to destroy the launchers on the territory of the Russian Federation, for example, with the help of Western Patriot and SAMP/T systems.

The morning of January 24 in Kharkiv began with an air alert because of the threat of tactical aircraft and the launch of anti-aircraft missiles. It was announced at 9:49 a.m. and did not last long — exactly half an hour. On the other side of the border in the Belgorod region, a siren also sounded. The danger was announced 22 minutes after the Ukrainian one, and the alert was lifted at 10:42 a.m. (11:42 a.m. Moscow time).

At 11:50 a.m. (10:50 a.m. Kyiv time), a message about the downing of a Ukrainian drone appeared on the Belgorod telegram channel, a local public service with 1,500 subscribers, Belgorod Online. Five minutes later, the governor of the Belgorod region, Vyacheslav Gladkov, posted on his telegram channel that an accident had occurred and that he was on his way to the scene. Residents and telegram channels published a 27-second video. At the 21st second, the plane is seen descending rapidly, going behind trees, and then bursting into flames, probably from a collision with the ground.

At 12:05 a.m. (11:05 a.m. Kyiv time), a video of the State Duma’s military committee meeting was posted on the Russian news outlet RIA Novosti’s TV channel. It reads: “An IL-76 military transport plane has crashed. The crew managed to report the use of external influence.”

Two hours later, the Russian propagandist Margarita Simonyan’s telegram channel publishes 65 names with the following note: “All of them are Ukrainian prisoners of war who were on board the IL-76 and were on their way to the exchange.”

At the same time, no official Russian body or federal media confirmed or denied the information provided by Simonyan.

Eventually, on January 24, Russian MP Andrey Kartapolov said at a meeting of the State Duma Military Committee that the plane was carrying 65 captured Ukrainian servicemen, six crew members, and three escorts.

At the assumption level

— On the morning of January 24, I went to class at the medical academy and saw the news about the downing of the IL-76. Everyone rejoiced because they thought it was our people who shot down the Russian plane. And half an hour later, the information changed. They said that the plane was Russian, but there were Ukrainian prisoners of war on board.

Around 16:00, a list of 65 POWs from my father’s brigade was thrown to the group of families of prisoners of war. And I read it: Sobolev… Yaroslav… Volodymyrovych. My mother and I did not believe it. We reassured each other,” recalls Sofia Soboleva, daughter of Yaroslav Sobolev, a soldier of the 24th separate mechanized brigade.

Her husband was taken prisoner on March 21, 2022, near Popasna in the Luhansk region. At first, he was held in the occupied territory, then transferred to Russia. The fact that the prisoner was being held in SIZO No. 2 in Vyazma, Smolensk region, was revealed to the family only on January 3, 2024.

Detention Center No. 2 in Vyazma, Smolensk region

The gleeful reports about the downing of the plane mentioned by Sophia Soboleva appeared on Ukrainian resources at 10:25 a.m. These were TV channels and media outlets, including Ukrainska Pravda. The latter noted that its sources in the Armed Forces confirmed the downing and the involvement of the Armed Forces in the shooting down. This news was later edited: “Sources in the General Staff claim that the plane was carrying missiles for the S-300 air defense system.”

In the evening of January 24, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine (GUR) stated that an exchange of POWs was indeed planned for that day but that the Russians had not informed the Ukrainian side of the need to ensure the safety of airspace during the exchange near Belgorod. “This may indicate Russia’s deliberate actions aimed at endangering the lives and safety of prisoners,” the intelligence report said. The GUR did not specify who exactly struck the plane.

The next day, Ukrainian Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights Dmytro Lubinets appealed to the UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross about the downing of the IL-76, calling for an international investigation. On January 28, he sent a letter to Russian Human Rights Ombudsman Tatyana Moskalkova, demanding information about the plane. Moskalkova responded only on April 5, noting that Ukraine had committed a terrorist act, mentioning the explosion in Olenivka, noting that Ukraine had again killed its prisoners of war who were dissatisfied with the state of the military command and the decisions of the military and political leadership.

The moment of the ILl-76 crash from another angle. Photo from Russian Telegram channels

— “In the evening, my mother received a call from the Coordination Headquarters and was invited to a meeting,” recalls Sofia Soboleva.

The rest of the families of the soldiers whose names were published by Symonyan were also invited to the Coordination Headquarters. The head of the Main Intelligence Directorate, Kyrylo Budanov, and the head of the Security Service, Vasyl Malyuk, attended the meeting. Budanov spoke about the plane crash and that Moscow was offering a green corridor for families to travel to Russia and provide DNA samples. At the same time, he insisted that the families not go anywhere.

— “They gathered us together and told us that no one was sure of anything, but we should trust them. They would do everything in their power to find out and investigate,” says Sofia.

The next such meeting took place on February 16, 2024.

— At it, we were told that they would conduct DNA examinations. I asked if I understood correctly that there were POWs on the plane and that they had died, but no one was telling us clearly about this. They said they were not sure,” recalls Oksana, the mother of a POW.

At the crash site

On January 25, 2024, the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation published the first video and information about the priority investigative actions in the area near the plane crash. The Russians post drone footage of the crash site online: without detail, they show fragments of bodies and paper documents. Russia reports that 670 fragments of 65 bodies were found. This figure does not include the crew and military police, who, according to Russia, were nine in total.

The location of the crash can be easily determined by identifying architectural objects in a resident video. A church is visible — the Church of Demetrius of Thessalonica. It is located in the village of Yablonovo, Korchansky district, Belgorod region. Its rector would later comment: “The church wasn’t damaged in any way during the crash. Nothing was damaged in the village. It fell outside the village, in the fields, five or six kilometers away.”

The tower of the the Church of Demetrius of Thessalonica in the village of Yablonovo as seen in a video still of the IL-76 crash moment (on the left) and on the church’s website

Few comments from witnesses were posted online. One of them reads: “Through the window at the post office, we saw a red object flying, oblong. Then, there was an explosion and a red flash. That was it. We didn’t see anything else. I heard only two explosions. The first one was so dull, and then the explosion.”

Another resident: “We heard a roar and went outside. There was already so much smoke, fire, and noise. There were two explosions with an interval of a minute, maybe less. The second one was louder. Then we ran out to see if you needed help. It fell far away, behind the village. It was deafening and scary.”

With the highest probability

On January 24, an IL-76 military transport aircraft with tail number RA-78830 was shot down in the Belgorod region. The plane was in service with Russia. Aircraft of this type are widely used to transport military cargo and personnel. According to the Flightradar online tracker, which allows real-time monitoring of aircraft worldwide, the IL-76 with this tail number regularly flew between Russia, Iran, and Syria. According to Flightradar, on January 24, 2024, starting at 9:00 a.m. Moscow time (8:00 a.m. Kyiv time) and onwards, this aircraft was not detected in the airspace of Russia or any other country. The transponder, a unique device on board used to identify the aircraft by air traffic control, was most likely turned off. At the same time, the aircraft is present in radio communications during this period with the call sign “86868”. At 10:16 am, there was a mention of the disappearance of Flight 86868 from the locators. At the same time, residents of the village of Yablonovo, 60 kilometers from Belgorod International Airport, filmed the plane crash. It shows the trajectory from the Ukrainian-Russian border. However, this trajectory is utterly atypical for airplanes landing in Belgorod.

The II-76 military transport aircraft

This leads to the theory that the IL-76 actually took off.

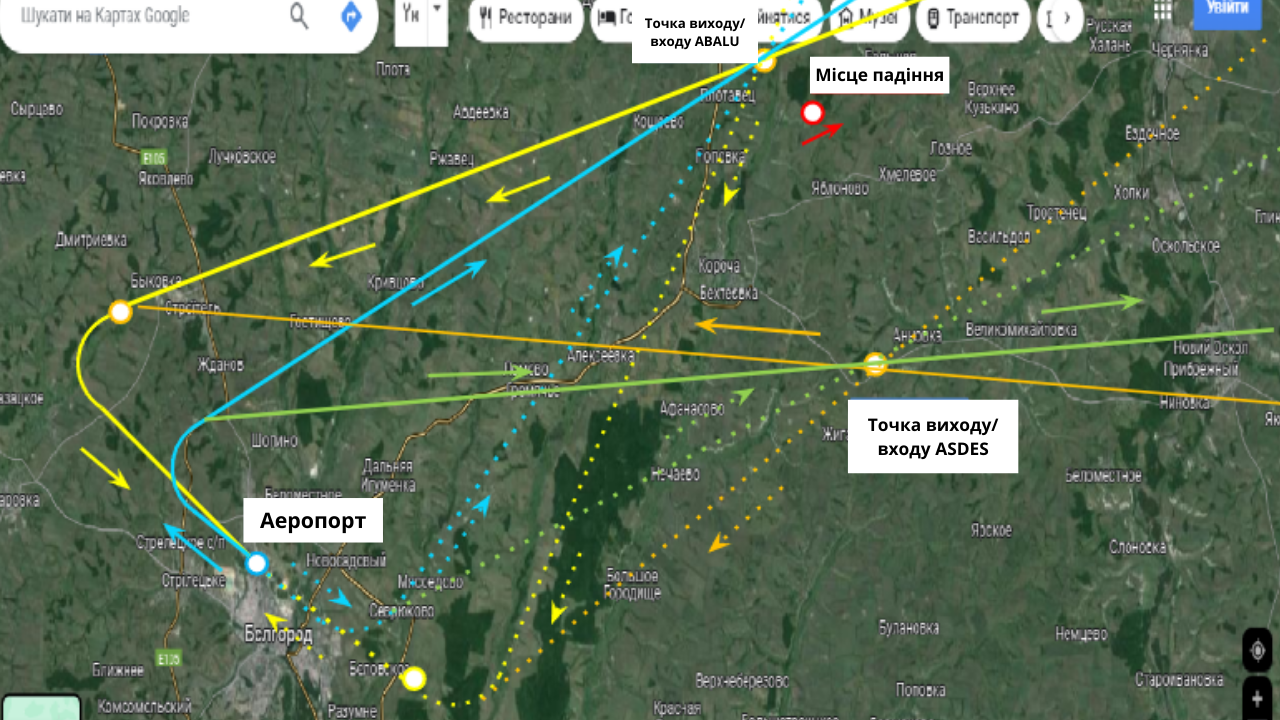

The MIHR asked aviation experts to analyze Belgorod International Airport’s takeoff and landing plan, the control navigation points, and the wind direction during the crash. They assumed the plane was traveling northeasterly, i.e., away from the border with Ukraine, when it crashed.

— This is also consistent with the location of the wreckage at the crash site. It is unlikely that the plane turned 180 degrees after being hit. I think that the direction recorded on the crash video roughly corresponds to the direction of flight before the aircraft was shot,” said Joris Melkert, an aviation specialist at the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

In the summer of 2024, the MIHR provided him with all available materials and links to open sources.

Possible entry (exit) points to the Belgorod CTR closest to the crash site

— “During the flight to the Belgorod airport, the aircraft would have to fly in a direction of approximately 245 degrees. This would have been consistent with a RASAP 4 approach. Alternatively, the plane could have landed or taken off in the opposite direction of the runway (109 degrees), taking advantage of a slight tailwind. If it were flying away from the airport, it would have taken off in a direction of approximately 65 degrees. This would correspond to a departure through point ABALU, located at 50°55’09N 037°17’08E, about 80 km from Belgorod Airport. The crash site near Yablonove is almost in a straight line between the airport and this point. So, based on the approach and takeoff procedures for the Belgorod airport and the direction of the crash, a likely scenario would be a departure through a point with these coordinates,” says Joris Melkert.

This means the plane has just taken off from the airport.

At the same time, the aviation expert emphasizes that his conclusion is based solely on the standard procedures approved for Belgorod Airport:

— “Controllers can always give pilots other instructions and order them to deviate from standard procedures.”

He also emphasizes that given the available data, including the video of the IL-76 crash and the way the wreckage is scattered, another condition is necessary to prove that the aircraft was taking off: to prove that at the time of the crash, the plane was no more than 1,000 meters from the ground. This condition is critical because the plane cannot turn even 150 degrees at this altitude.

Fragments of the Russian IL-76 aircraft that crashed over Belgorod

If we take the altitude of 4,000 meters, at which Russia claims the crash occurred, as a basis, then a second version emerges — the plane was landing. Depending on the damage, the plane could have spontaneously turned 360 degrees at that altitude.

The Russians claim that the plane was flying to Belgorod from the Chkalovsky military airfield in the Moscow region. “According to video footage from an outdoor surveillance camera, the plane was hit by two missiles: the first at an altitude of about 4,000 meters, the second did not reach its target and self-destructed,” the official statement of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation reads.

The question arises as to how an airplane coming in for a landing could be at an altitude of 4,000 meters near the airport.

This is possible when a ship performs a so-called Afghan landing, during which the aircraft descends from a much higher altitude than a standard landing. This maneuver significantly reduces the time the aircraft spends in the combat zone and enemy air defense systems. The Afghanistan landing is performed only in manual control mode and requires extraordinary skill from the crew, but it is possible for the IL-76.

Although it is not known for sure whether the plane was taking off or landing, there is little doubt that a missile shot down the plane.

— “It could be a surface-to-air or air-to-air missile,” says Joris Melkert, “The wreckage shows a characteristic pattern of shrapnel damage caused by the explosion of such a missile. However, the photographs of the missile wreckage are of little importance, as they were not examined by an independent commission to investigate the crash site. Everything said in this regard may be either true or false.

There is also information about the deaths of nine Russian citizens on that day in the Belgorod region: six crew members and three supervisors who allegedly accompanied Ukrainian prisoners of war. The Schemes project (Radio Liberty) identified the names of the crew members. The deaths of three of them were confirmed by their relatives the day after the crash. These are the ship’s navigator, Alexei Vysokin, commander Stanislav Bezzubkin, and flight engineer Andrey Piluyev.

From right to left: Stanislav Bezzubkin, Andrey Piluyev, Alexei Vysokin. Crew members of the IL-76 aircraft who, according to Russian sources, died in the plane crash in Belgorod region on January 24, 2024

Under the photo of another crew member, the onboard radio operator Ihor Sablinsky, social media posted condolences on his death. The flight was also supposed to be serviced by airborne equipment flight engineer Sergei Zhitenev and assistant commander Vadim Chmirev.

The crew belonged to the 117th Military Transport Aviation Regiment, a military unit No. 45097 in the Orenburg region. From open sources, the MIHR has established that this regiment is engaged in servicing military vehicles that transport special cargo for the material support of the Russian army. The 117th Regiment’s aircraft are based at the Orenburg-2 airfield. Its planes and crews took part in the military operation in Syria, for which its commanders, navigators, and others were awarded decorations.

Among the names of the guards who allegedly accompanied the POWs, only one was mentioned — Ihor Havrysh.

Preparation for the exchange

The Russian supervisors came for POW Andriy Stepanov on January 23, 2024. At that time, the State Border Guard Service colonel was held in Detention Center No. 2 in Kamyshyn, Volgograd Region. He was taken prisoner in May 2022 while leaving Azovstal. Stepanov, along with nine other POWs, was put in a car. They were being driven for a long time.

— When the van stopped, a colonel of the FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service) came in. We didn’t look at him – we were used to it. We couldn’t raise our heads. He said: “You are going for an exchange, everything is fine, you will be home soon,” Stepanov recalls. They brought us to some other prison. They were supposed to take another person. It turned out that they were taking him to Kamensk-Shakhtynsky (Rostov Region). When they took him, they took two more people. I think it was Taganrog. In the morning, we arrived at an airfield. They tied our hands and eyes with tape and put us on the floor of the plane. It was an IL-76.

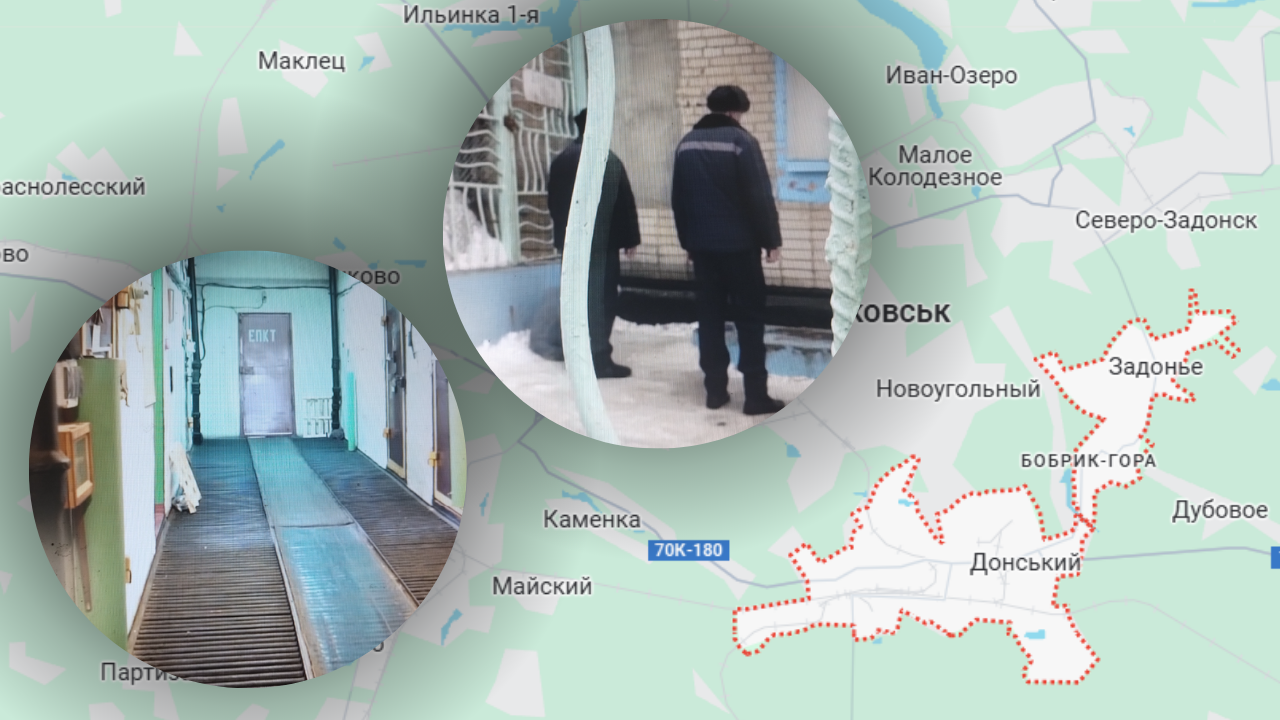

Correctional colony No. 1 in the city of Donskoy, Tula region

The plane took off into the sky.

— About an hour into the flight, the Russians started to panic. “You b***hs should be shot here. Your guys shot down a plane with prisoners of war,” they started shouting. We felt the plane turn around and fall on its side. We were flying for a few more hours. The time was dragging on. We landed at the airfield from which we took off. We were ordered to get off the plane. There were 13 of us.

Former POW Ian Bordianu says that he was held in Mordovia in prison no. 10. On the night of January 23-24, they were forced to march in place for a long time. He and two others were ordered to pack their belongings for the exit and were taken away in a car. They drove for a long time, about 12 hours.

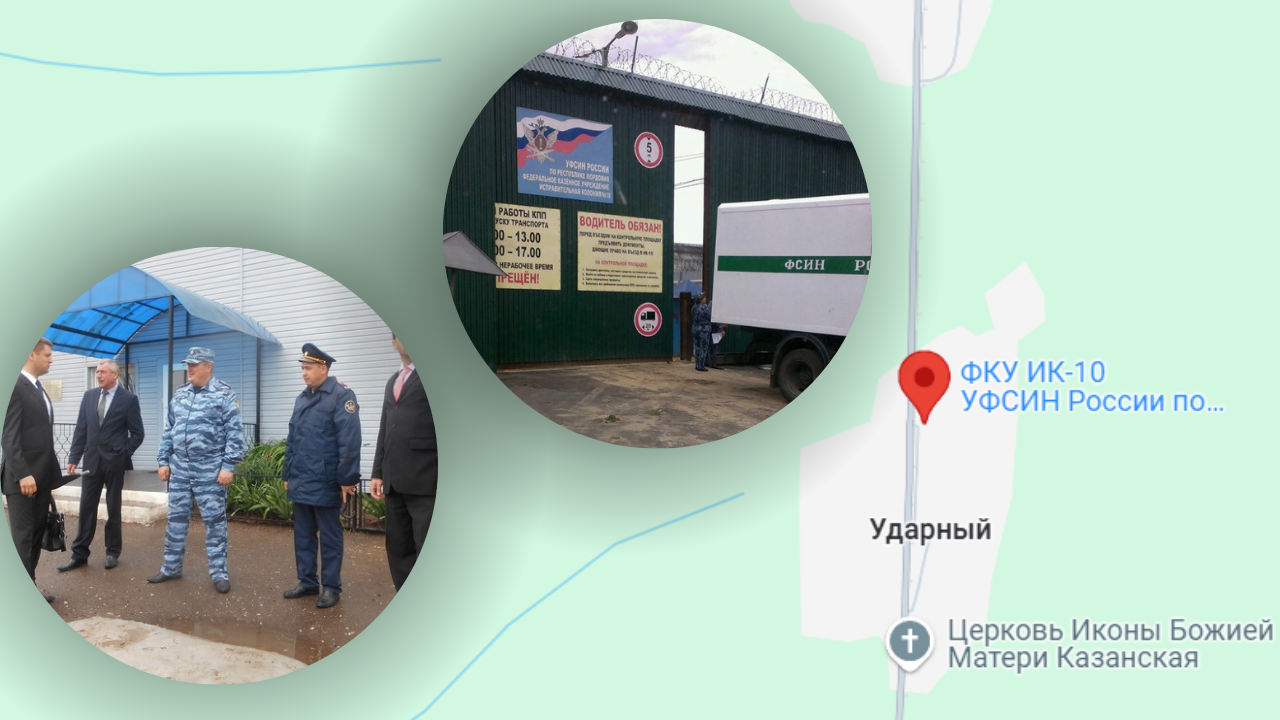

Correctional colony No. 10 is located in the village of Udarny in the Republic of Mordovia

— They brought us to the airfield, I don’t know which one. There were a lot of vans from which prisoners got out and took turns getting on the plane. We flew for several hours without landing. On the plane, they said: “Your plane was shot down. There will be no exchange.” The plane was turned back.

Both Stepanov and Bordiyana, as well as several dozen other prisoners from this plane (it is not known precisely how many; all Ukrainian soldiers were blindfolded,) were placed in colony No. 12 in Kamensk-Shakhtynsky.

Volodymyr Miroshnychenko was also supposed to be exchanged on January 24. He was held in Vyazma, Smolensk region. That day’s night, he was taken in a truck, then transferred to buses, and there he was informed: “Your country has refused to exchange you.” Miroshnichenko was not brought to the plane or his intended destination. He and the others were transferred back to the buses, taken to some colony, and moved to other buses. Later, the guards drank alcohol and beat the prisoners. One of them shouted: “Do you know why you were refused? Your men shot down the plane and interrupted the exchange.”

In addition to the downed plane, the Russians probably used another IL-76 that day. MIHR received information about this from its intelligence sources, where we were told that after the downing of the IL-76, two more aircraft heading towards Belgorod were ordered to fly to alternate airfields, including Chkalovsky in the Moscow region. However, we cannot confirm that these were the planes that were transporting Ukrainian prisoners of war.

The Investigative Committee of Russia at the site of the IL-76 crash in Belgorod region

On the eve of 2024, pro-Russian propagandist of Ukrainian origin Anatoliy Shariy posted a list of more than 300 names of prisoners of war whom Russia was allegedly ready to hand over to Ukraine on his telegram channel. It mentioned Andriy Stepanov, Ian Bordianu, and Yaroslav Sobolev.

— The first exchange took place on January 3. Then 230 people were returned, including those on Shariy’s list. So we in the family assumed that our Yaroslav would be exchanged the next time,” says Sofia Soboleva.

Margarita Simonyan published the list of 65 POWs after the crash of the IL-76, which also included names from Shariy’s list.

The MIHR has analyzed the list in detail and found witnesses to the detention of at least 21 prisoners of war. Some were seen on January 3, and some on January 22-23, 2024. Most of them are in SIZO No. 2 in Vyazma, Smolensk region. Several were seen in the Udarny village of Zubovo-Polyansky district of Mordovia, the Pakino city of Vladimir region, and the Donskoy city of Tula region. Witnesses say that the general health of these prisoners was satisfactory.

The route of transporting Ukrainian prisoners of war to Russia before January 24, 2024. Graphic: MIHR

Andriy Stepanov was returned to Ukraine during the exchange of prisoners of war on January 31. At that time, others taken from Kamyshyn and several other places of detention in other regions of the Russian Federation were also exchanged.

— On January 31, the plane was delayed for several hours, taking off two hours later than they expected — we heard about it from conversations. They flew for a long time again. Or so it seemed to me, from the airplane to the buses. In the buses, the guys started whining that this was not an exchange because we were traveling in buses. And so on for several hours. After that, we were transferred to buses. We also traveled in them for more than an hour. We were exchanged at the Sumy border in Kolotylivka,” Stepanov says.

Bordianu was on the same plane. He adds:

— “I think they landed in Belgorod. But he is not sure.

Russian propaganda

— “After that plane crashed, they started calling me daily.”

— “What plane?”

— “IL-76’. My friends began to say that my relative was on the list that was made public after the crash. And then I got a call from the ‘counter-terrorism department,” tells MIHR Serhii.

— “From the FSB?“

— “Yes. At first, the so-called investigator asked me why he had signed a contract with the armed forces and how I had learned about the IL-76. But it was okay. He let me go. After a while, the investigator came back and said: “You have to give an interview to a Russian TV channel and say that Ukrainians shot down the plane.” I refused. While we were talking, the house was being searched.“

— “I will try to work with my superiors to make sure that you are not bothered anymore,” the investigator continued, “If you give an interview, no one will bother you.“

This dialog is part of a conversation with a relative of one of the POWs whose name is on the list of 65. We are not naming both of them for security reasons. Still, we know for sure that in the occupied territories, Russians came not only to this family but also to others whose relatives were under occupation. They demanded that each of them record a propaganda video in which the responsibility for the downing of the plane was assigned to Ukraine.

Russia used the crash of the IL-76 for propaganda, producing messages for its domestic audience. And this is not the first time. At the beginning of this investigation, we mentioned how the Russian ombudsman Moskalkova, responding to a request from her Ukrainian counterpart Lubinets, mentioned the Olenivska colony in her letter on the circumstances of the IL-76 crash, where at least fifty-two Azov soldiers were killed by Russians. Russia also blamed Ukraine for their deaths, claiming that the HIMARS system had fired upon the barracks with the Azovs. In the case of the IL-76, Moskalkova says the plane was shot down with a Patriot system.

Fragment of the Russian IL-76 aircraft that crashed over Belgorod

— “The actions of the Russians in such cases are very similar — they need to quickly fill the information space with their narratives, manage them, and make the story favorable to them,” commented experts of the StopFake analytical project.

“So the beginning of the accusation of Ukraine of shooting down the IL-76 was the same as after the downing of the Malaysian Boeing flight MH17 over the Donetsk region. All Russian disinformation campaigns are similar: they use all channels to spread various fake messages, comments, and promises to provide objective evidence. However, while in the case of MH17, Russia did everything to absolve itself of the apparent guilt, with the IL-76, Russia wanted not so much to absolve itself of the fact of guilt as to invent a war crime from scratch, accusing Ukraine of it.

StopFake experts assume that the versions and messages were prepared because the messages looked like the plane crash was expected, so the information space was filled with no alternative position on who was to blame and why.

However, the information wave quickly subsided. And this is quite surprising because the plane crash occurred on the territory of the Russian Federation. Moreover, if we assume that the plane was indeed shot down by a Ukrainian missile, Russia should have found the wreckage and shown it to the world as evidence. However, this has not happened in a year.

Open questions

Throughout the year, the MIHR investigated not only the flight path of the plane but also the routes used by Russia to transport prisoners for exchange.

We also tried to find out whether there were Ukrainians on board the downed IL-76.

Considering the version that the plane took off rather than landed, we assumed that the Belgorod airport in this story was an intermediate point for the transportation of Russian military personnel from the Middle East. This version was supported by several facts, including regular flights of Russian IL-76s to Iran and Syria and public statements by Russian officials. Hence, the presence of Ukrainian prisoners of war on the plane seemed illogical.

When the version of the plane’s landing was taken as a basis, we assumed that the vessel was carrying either ammunition and Russian soldiers or, most likely, Ukrainian POWs.

The information about the return of the bodies to Ukraine did not clarify the situation. It is currently impossible to say whether these are the same bodies that the Russians allegedly found at the crash site of the IL-76. First, the Ukrainian side does not have access to the crash site, and Russia does not provide objective data on the crash and does not allow international experts to investigate. Second, over the past year, Russia has repeatedly returned the bodies of Ukrainians tortured in captivity. Therefore, there is no certainty that under the guise of those killed in the IL-76, the Russians are not returning the bodies of those who were tortured in prison.

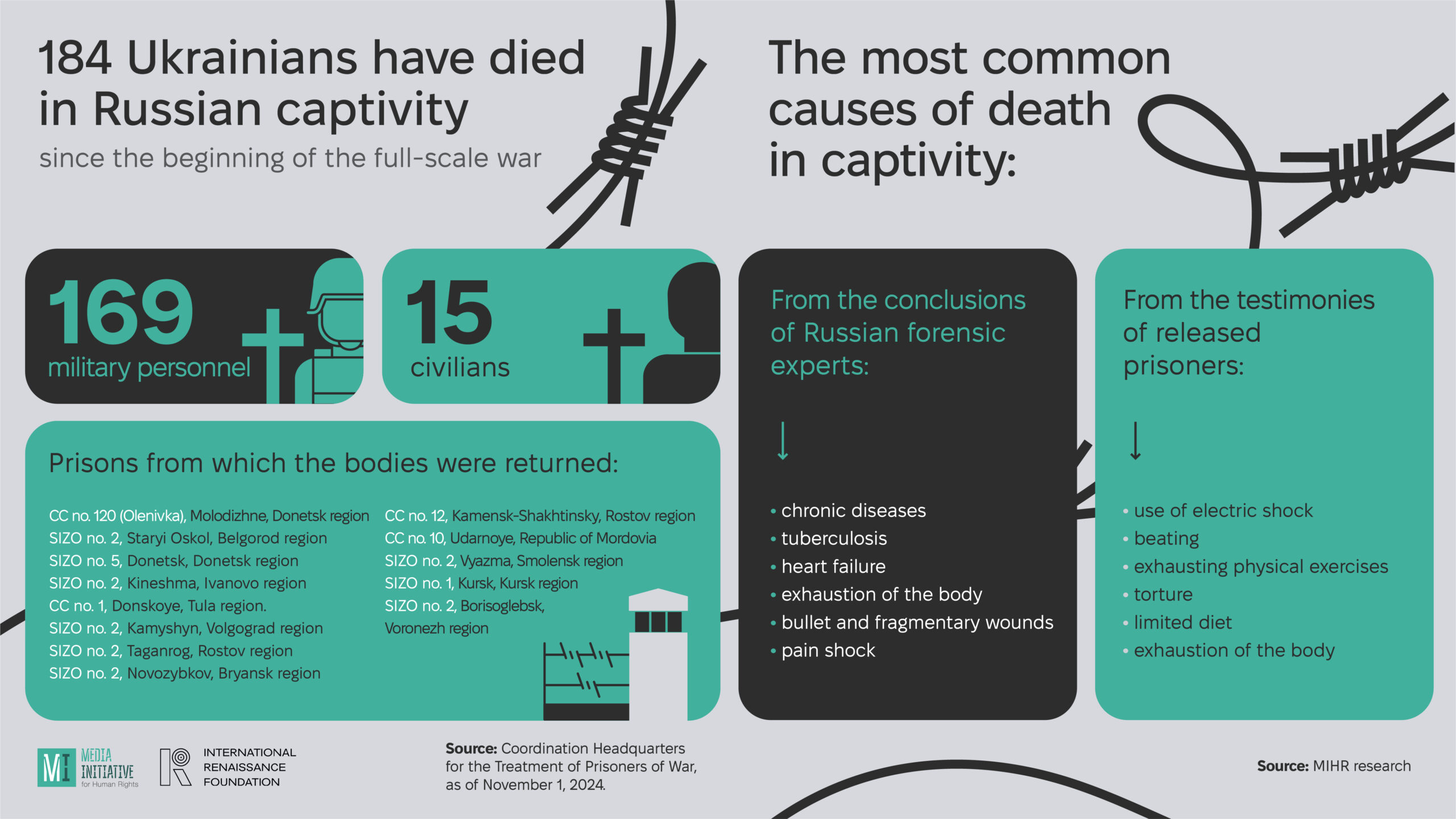

Infographic by MIHR

For example, during the release of photos from the crash site, Russia showed fragments of bodies with tattoos. After that, it was reported that one of the prisoner of war’s families recognized the tattoos. However, the MIHR could not verify this information – the family refused to talk to journalists. Instead, we found a former prisoner of war who was in captivity at the time of the plane crash. He had seen Russian news reports showing fragments of bodies with the same tattoos and claimed that these people were later returned to Ukraine in exchange.

The examinations of the transferred bodies are currently underway. Although there are matches, not all samples are identical. At some stage, experts from the International Commission on Missing Persons may be involved in the process, as they have extensive experience in identifying those killed in armed conflicts, including those who were on Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 in the skies over Donetsk region in July 2014.

From its sources in law enforcement agencies, the MIHR knows that the body fragments, which Russia calls the remains of Ukrainians killed in the IL-76, were returned in a condition that does not allow for comprehensive identification to determine the cause of death.

What caused the plane’s downing also remains unclear. According to Joris Melkertu, a specialist at the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, it could have been a surface-to-air or air-to-air missile.

Commenting on the downing of the IL-76, sources close to the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces noted:

“Transportation of prisoners of war by military transport along the front line is a war crime. They would have put them in tanks and driven them toward Kharkiv. If the air defense forces had seen the passenger plane, they would never have fired a missile.”

Nevertheless, Russia uses military transport, in particular IL-76 aircraft, to transport prisoners of war. This is evidenced by former prisoners released from different places of detention and at different times.

The crash site of the military IL-76 aircraft in Belgorod region

When asked whether the air defense forces near Kharkiv could have known about the exchange scheduled for January 24, 2024, the sources of the MIHR answered that they did not. Instead, they claim that they had intelligence that stated that the Russians were bringing S-300 missiles to the Belgorod airport by IL-76 aircraft. This airport has long been closed to civil aviation. No one declared a ceasefire that day. The HRMMU has information about the recorded conversations of three Russian tactical/fighter aircraft at the launching sites near the Kharkiv region between 10:05 and 10:11 Kyiv time that day. MIHR sources in the Defense Forces state that the ceasefire was declared in a completely different area, where the exchange of prisoners of war was to take place: between the Russian point of Kolotylivka in Belgorod region and the Ukrainian Pokrovka in Sumy region.

Russia and its responsibility

Andrii Yakovliev, lawyer, managing partner of Umbrella Law Firm, expert of the International Humanitarian and International Criminal Law, emphasizes that Russia is fully responsible for the downing of the plane with Ukrainian POWs (if it really happened). This can be qualified as the intentional or deliberate killing of Ukrainian prisoners of war, i.e., a war crime.

Yakovliev names several key factors that establish Russia’s responsibility and exclude Ukraine’s responsibility.

First, on the eve of the plane crash, Russia exerted pressure and attacked Ukrainian territories, including civilians. In January 2024, active hostilities took place in the Belgorod region, and the Russian authorities introduced air raid sirens in Belgorod and the surrounding areas, in particular due to the use of drones by both sides of the conflict, which created a dangerous air situation in the adjacent regions.

By January 24, 2024, the Russian Federation attacked Kharkiv using S-300 ballistic missiles, which were probably delivered by air to Belgorod International Airport.

— “That is, obviously, when Russia sent a military aircraft to the Belgorod region, it realized that it was sending it to a high-risk area,” the lawyer said.

Andrii Yakovliev, expert of the International Humanitarian and International Criminal Law

Secondly, there is publicly available information that until February 24, 2022, the Belgorod airport served civilian flights, while during the hostilities, the Russian army began using it exclusively for military purposes, as satellite images recorded the deployment of military aircraft and equipment on its territory.

Earlier, the Federal Air Transport Agency of the Russian Federation reported that all flights at the Belgorod airport and other airports in the central and southern part of the Russian Federation were “restricted” due to the hostilities.

— “The Russian Federation, in accordance with international rules, in particular the Chicago Convention of 1944, has established no-fly zones for civilian aircraft in its airspace, which includes the war zone,” continues Andrii Yakovliev.

He explains that if Russia sends military aircraft to such a zone, they are legitimate targets for Ukraine. And the enemy cannot transport POWs, who are, in this case, considered civilians under international humanitarian law.

And most importantly, Russia is responsible for the lives and health of the military it has captured.

— “Article 19 of the Third Geneva Convention requires that prisoners of war be placed in an area that is located at a sufficient distance from the hostilities to ensure their safety,” says Andrii Yakovliev, “and Article 23 of the same convention prohibits the transfer of prisoners of war to areas where they may be threatened by fire from the combat zone, and they cannot be held in such places. In addition, it is forbidden to use their presence to protect any objects or territories from military operations, i.e. to hide behind them as a human shield.

In other words, it appears that Russia deliberately sent a military aircraft to its inevitable demise in the zone of legitimate destruction of the Ukrainian air defense system.

— “The laws and customs of war provide for the obligation to distinguish between military and civilian objects and the population. This means that the military must attack only military targets. And what is an IL-76? It is a military transport airplane, so it is a military target. This plane becomes a civilian object if there are civilians and persons equated to them only if the opposing side knew about it or could not help but know about it. That is, Russia should have informed Ukraine of the specific route of this plane and that it was carrying passengers,” Andrii adds. ”When distinguishing between objectives, it is taken into account how the other party can make this distinction, in particular based on the principle of ensuring precautionary measures. All of these are important elements of International Humanitarian Law, but Russia did not comply with them. Therefore, in such circumstances, a military aircraft is a legitimate military target for any air defense system in the world.”

There is no evidence that Russia informed Ukraine about the transportation of prisoners of war and the need to organize a secure air corridor. Moreover, Russia tried to hide the plane by turning off its transponder, as we wrote at the beginning of the investigation.

Under such circumstances, there is every reason to believe that Russia deliberately planned actions that created a deadly situation, resulting in the deliberate killing of POWs. And this is undoubtedly a war crime.

— “Thus, the Russian Federation can be considered guilty of committing a war crime – the intentional murder of Ukrainian prisoners of war, as it did not comply with the Third Geneva Convention prohibiting the transfer of POWs to a combat zone and/or shot down the plane itself, or deliberately created a dangerous situation that led to the tragedy. Therefore, it is Russia that is responsible for the deaths of Ukrainian POWs,” emphasizes Andriy Yakovlev, an expert on international humanitarian law. ”And the fact that Russia does not provide evidence of the report of using a military aircraft for non-military purposes (i.e., to transport prisoners) increases the likelihood that the IL-76 could have been attacked by Russia’s own air defense system. The goal is clear: to blame Ukraine for this in order to undermine the supply of Western weapons to Ukraine.”

Fragment of the Russian IL-76 aircraft that crashed over Belgorod

An important detail in favor of the extreme version of the Russian air defense system and its deliberate downing of the IL-76 is that on the day of the crash, there were no representatives of the Russian Defense Ministry’s negotiation tea.m. on board, who always fly with prisoners and are present during exchanges. In particular, General Sergei Yegorov traveled by train.

Following the news of the downing of the IL-76, the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine registered the information in the Unified Register of Pre-trial Investigations on the grounds of a criminal offense under Part 2 of Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. The pre-trial investigation is being conducted by the Main Investigation Department of the Security Service of Ukraine. “All necessary measures are currently being taken to ensure a prompt, complete, impartial investigation, to establish all the circumstances of the crime and the persons involved in its commission,” the Office of the Prosecutor General told MIHR. They refused to disclose any details, citing the secrecy of the pre-trial investigation.

Through the eyes of family. Epilogue

— “In June 2024, I saw information on social media that Russia had handed over letters from prisoners of war,” says the mother of a prisoner of war. “And on August 6, I received a call from the Office of the Ombudsman and was told that there was a letter for me. I asked about the date. I said, “You know who you’re calling,” and they told me that my son was in the IL-76. But it seems to me that they did not understand who they were calling. When I received the letter, it was undated. Roman wrote that he was a “strong guy,” that he would endure everything so that we would not regret anything, but live a normal life and take care of ourselves.

Probably, Oksana’s son wrote this letter in early 2024, before January 23, when he was last seen by other prisoners in the colony in Pakino.

Relatives interviewed by the MIHR during this investigation cite a lack of information from the state and its uncoordinated actions. Throughout the year, representatives of various bodies involved in the search and release of prisoners and the investigation of the crime repeatedly issued different versions of events, stating either the presence or absence of Ukrainian prisoners of war on board the downed IL-76. Russia also evades providing objective information.

All of this hurts the families of the military whose names were on the list of the IL-76. In one voice, they say that it seems they are trying to hide the truth from them. A year has passed, but there are still no official answers to the questions of where the plane was going, who was on board, what caused it to crash, and who is to blame.

Authors: Tetiana Katrychenko, Kateryna Chernata.