Accused of espionage and jailed while pregnant. The story of Oksana Parshyna’s imprisonment

Oksana Parshyna is 36 years old and the mother of two sons. She gave birth to her youngest child in occupied Donetsk, where she received a 10-year prison sentence from the Russian-controlled “Donetsk People’s Republic.”

On May 14, 2021, Oksana was detained by representatives of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” while crossing the uncontrolled section of the Russian-Ukrainian border at the Marynivka checkpoint. Despite being only two months pregnant at the time, she was interrogated and subsequently transferred between multiple detention facilities.

We met with Oksana at a hospital in Lviv, where she was being treated for health issues related to her imprisonment while pregnant, which were worsened by the inappropriate conditions she was subjected to. She had two hernias removed. Oksana bravely shared her harrowing story with us to the ominous sound of an air raid alarm.

— Born and raised in Donetsk, I lived there until the start of the war in 2014. Following that, I began traveling to Mariupol to study Polish as I wanted to obtain a Pole’s card due to my Polish heritage.

Determined not to live under occupation, I witnessed firsthand the atrocities committed by the DPR military, including the senseless shelling of civilian homes with tanks. Even my own home near the Donetsk airport was bombed. In response to these injustices, I began assisting our military by providing them with information on the location of enemy units and equipment whenever I could.

In 2016, I relocated to Mariupol, though I continued to make occasional visits to Donetsk to visit my remaining relatives who still lived there.

Upon learning about my second pregnancy, my husband and I made the decision to purchase an apartment in Mariupol. I still owned property in Donetsk, so I was en route to resolve some matters with that apartment when I was detained at the border on May 14.

I was confined to a room near the border, and my personal belongings and phone were confiscated. After an agonizing 4-hour wait, I was taken into custody and driven to the “DPR MGB” office in Donetsk.

The “MGB” refers to the Ministry of State Security of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic,” which is under the control of the Russian government. Its headquarters are located at 26 Shevchenko Street in Donetsk.

— They started interrogating me there. They asked me where I went, what I did: “Did you film military units?” They held me until night, gave me nothing but water, and allowed me to go to the restroom once. I immediately told them that I was pregnant, but they knew it from checking my phone earlier. They threatened me, demanded that I confess to taking pictures of their military facilities: “If you don’t start talking, we’ll hit you now, and you won’t have a baby.” So I admitted my guilt.

After the interrogation, I was taken to the basement, where there was a small room with bars instead of doors, the windows were boarded up, there was no light at all, and there was a blanket and a six-liter cut-off bottle on the floor for “personal use”. They gave me only water.

After two days there, they came for me again. They put handcuffs on my hands, a bag over my head, and took me somewhere. When they took the bag off, I realized that we were standing in front of the Vyshnevsky Hospital. There, I had a PCR test for coronavirus and an ultrasound, which showed that I had some problems with my pregnancy, and the doctor said I had to lie down all the time.

Central Clinical City Hospital No. 1 in Donetsk, located at 46 Rosa Luxembourg Street

— However, at the prison, they took me to from the hospital, it was impossible to follow the doctor’s recommendation. Before the occupation, it was a Donetsk location of contemporary art, and now it is a DPR torture chamber called “Izolyatsia,” where you have to do something all the time, clean, and wash. When I was brought there, there were already women there. One of them was in terrible condition; all her teeth were broken. At that time, she had been in “Izolyatsia” for 20 months. During this time, she was waterboarded and electrocuted there.

The “Izolyatsia” prison is a secret prison of the “DPR Ministry of State Security”, established in 2014 in the building of the International Charitable Foundation IZOLYATSIA. Platform of Cultural Initiatives at 3 Svitlyi Shlyakh Street. There are cells on the first floor and administration offices on the second floor. Other premises on the territory of the prison are used to store humanitarian aid from the Russian Federation and weapons.

Schematic map of the Izolyatsia prison. Photo: NV

If you don’t know the DPR anthem, you will get beaten up.

— The ladies immediately warned me that I had better learn the DPR anthem, that if they asked me and I didn’t know it, they could beat me up. We had certain rules. As soon as one of the guards entered the cell, we had to put bags over our heads and turn our backs to them. They also took us out for a walk with a bag on our heads, and as soon as the gate closed behind us, we could take the bags off.

It was immediately clear that we were not being held in a specialized prison. It looked like someone’s private home, big enough for homemade cells with bunk beds welded together. We were constantly moved from cell to cell, and each new cell had to be cleaned and washed. I spent four days there.

And then I was taken to a new prison. I was brought to a temporary detention center. The food there was just terrible: undercooked porridge, cutlets made from food waste, but I still forced myself to eat.

They told me that if I signed a confession that I was a traitor, they would keep me there for 30 days and then release me. I was ready to do anything for my child.

But, of course, they did not release me. On June 11, 2021, I was accused of espionage and a criminal case was initiated against me. On June 15, I was transferred to the Donetsk pretrial detention center.

For a fleeting moment, life at the Lviv hospital where we are interviewing Oksana comes to a standstill. We hear the sounds of explosions nearby.

— This must be an elevator, — I tell Oksana.

— No, trust me, I have heard this sound much too often, — Oksana replies.

The hospital staff and patients look out the window, but no more explosions are heard. “These are our air defenses,” one of the doctors says. And the noise of the hospital returns.

Oksana with children. Photo from a home archive.

I was afraid to sleep; sometimes I stood in front of the mirror and thought that I would stop this torment myself.

— At the detention center, I was placed in a barracks for women with children. At the time, there were two of us there: me and a woman with a child who had stabbed men twice. The way she treated her child was terrible. Sometimes I would just put my hands over my ears and a pillow over my stomach, talk to the baby, tell him not to listen to this, that I love him and will protect him.

Our guard was a woman, and I was terrified of her. She was a sniper, she knew under what article I was accused, and she deliberately told me how many Ukrainian soldiers she had killed to make me even more afraid.

Once they took me for an ultrasound, and the doctor said that my placenta was low, so I had to lie down all the time. When they brought me back, they told everyone that I was not allowed to work. Then a very strong moral pressure began. The female guard told me every chance she got what she would do to me if she was allowed. I was afraid to sleep, sometimes I stood in front of the mirror and thought that I would end this torment myself. But then I would start stroking my belly, remembering that my husband and eldest son were waiting for me in Ukraine.

When I was 26 weeks pregnant, an ambulance took me from the detention center. My eldest son’s birthday was in September, and I was very worried that I was not there for him, that I did not take him to the first grade. So I had a fever and started having premature contractions.

They brought me not to a regular hospital but to a department for people with COVID. The test was not performed immediately. My COVID diagnosis was confirmed, but treatment began only two weeks later. All the time I was in the hospital, I had security guards with me, I even went to the restroom at gunpoint.

During this time, my story began to circulate widely on social media, drawing significant attention to my case. Given my precarious health condition, a return to prison would have surely worsened my situation. Thus, I was ultimately released on my own recognizance, albeit with the condition that I remain confined to my apartment in Donetsk, except for medical appointments.

Sensing that something was amiss with my unborn child, I sought out an ultrasound, but I was trailed by my captors the entire time I was out of the house. Unfortunately, the results showed that my baby was suffering from intrauterine hypoxia, necessitating that I spend more time outdoors. Only after this revelation were the conditions of my detention marginally relaxed, and I was granted permission to walk within the adjacent premises.

Despite the arduous circumstances of her pregnancy, Oksana successfully gave birth to a healthy son, Leonid, in December 2021. Holding her newborn in her arms, she persisted in her efforts to secure her own release, even penning letters to the self-proclaimed “DPR” Human Rights Ombudsperson, Daria Morozova, imploring to be included in any potential prisoner exchange list. Regrettably, all her attempts proved futile.

The so-called court hearings dragged on until August 2022, at which point Oksana was “sentenced” to 10 years in prison. The sentence was suspended for 14 years until her son reaches the age of 14.

Throughout this period, Oksana was prohibited from leaving Donetsk, despite her attempts to explain that her elder son was in the territory controlled by Ukraine. Unfortunately, neither the “prosecutor” nor the “attorney” took this into consideration, even cruelly mocking her “Are we not going to liberate that part of Ukraine?”. To add insult to injury, they also offered Oksana the choice of relocating to Donetsk with her husband and eldest son, an option which she vehemently rejected.

Undeterred by the risks, Oksana Parshyna bravely shared comments on social media and pleaded for assistance. She simply couldn’t bear the thought of her older son enduring yet another year without his mother, and she wanted to celebrate her younger son’s first birthday in a free and democratic Ukraine.

After being advised to write a letter requesting a pardon, Oksana was fortunate enough to be granted clemency. Nonetheless, she was compelled to wait and plead for three months to obtain a copy of the pardon document, without which she remained trapped within Donetsk.

Oksana and her little Leonid are welcomed home. Photo from Oksana Parshyna’s home archive

Finally, on December 15, 2022, after an arduous six-day journey, Oksana Parshyna and her young son were able to depart from the territory under Russian occupation and enter the free territory of Ukraine.

Oksana Parshyna’s case is being handled by Ukrainian lawyer Andriy Yakovlev, managing partner of Umbrella Law Firm, an expert with the MIHR. Here is his vision of this story:

Andriy Yakovlev, attorney

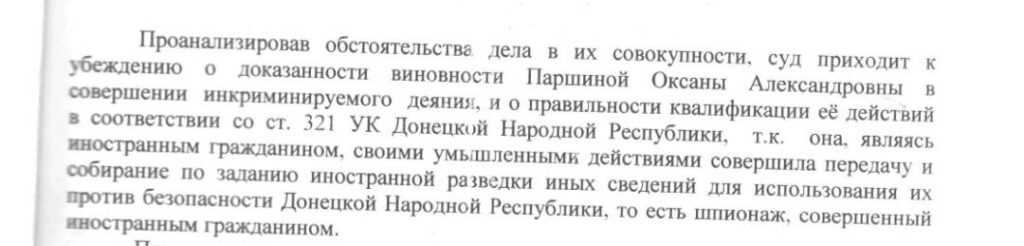

— Oksana was detained on May 14, 2021, while attempting to cross the border, but it wasn’t until June 11 of that year that a criminal case was initiated against her. She was formally indicted on November 10, 2021, and ultimately sentenced by the occupation court on August 29, 2022. Here is an excerpt from the court’s decision:

Oksana was accused of espionage by the Russian Federation on the basis of her own self-incriminating testimony, which was extracted while she was pregnant and under arrest. Throughout her ordeal, she was deprived of legal aid, contact with the outside world, and access to her own family. Her pregnancy was further imperiled by the constant threat of physical violence.

The right to freedom from self-incrimination is a universally acknowledged principle of international law, which safeguards the fundamental presumption of innocence. The violation of this right, particularly in instances where the voluntariness of self-disclosure cannot be ascertained, strongly suggests that Oksana was subjected to criminal prosecution replete with significant human rights abuses and violations of fundamental freedoms.

The laws and customs governing warfare, including Article 75 of the Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, dictate that in cases of criminal offenses linked to armed conflict, no individual shall be convicted or punished except by an impartial and duly constituted court. This court must adhere to universally recognized principles of ordinary justice, which guarantee the right to a defense and preclude any form of compulsion to testify against oneself or confess to guilt.

The verdict rendered in the case of Oksana Parshyna was delivered by a court that was established in blatant contravention of the laws and customs governing warfare. As a result, the defendant was systematically denied the fundamental right to a fair and impartial trial, which represents a flagrant violation of the Geneva Conventions, amounting to a war crime.

Furthermore, it should be noted that Oksana Parshyna was both pregnant and had a young child in her care. In light of the resultant deprivation of her liberty, coupled with the inhumane treatment that she endured – which can be deemed tantamount to torture in its severity – and the deprivation of her rights to communicate with the outside world and a fair trial, it is evident that Oksana Parshyna is the unfortunate victim of a war crime.

The material is published with the support of the Prague Civil Society Centrе.