Courts in Evacuation: How the War Has Redefined the Landscape of Ukrainian Justice (Infographics)

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine for the second time since 2014 has had a profound impact on the country’s judicial system. Dozens of courts have been displaced, meaning that their territorial jurisdiction has been changed, while hundreds of judges have been ordered to change their place of work. The conflict has also raised questions about the restoration of case files lost due to the hostilities and the accuracy of information about “collaborator judges”.

What are the interim outcomes of the large-scale relocation of courts from the temporarily occupied territories, and what issues have arisen within the judicial system during this process? Furthermore, has the experience gained from the 2014 conflict been applied in ensuring continued access to justice? The MIHR article sheds light on this.

Twice Displaced

The Donetsk Court of Appeal has weathered two periods of occupation. Prior to 2014, it provided judicial oversight to 55 local courts in the area and operated out of two locations: Donetsk and Mariupol.

Natalia Misko, the court’s chief of staff, has stated that the court’s operations in Donetsk were thrown into limbo in early 2014.

“From May to June of that year, the court staff continued to work, filing cases and archiving them as usual. However, in September 2014, the building of the Donetsk Court of Appeal was seized by illegal militia groups, leading to the suspension of operations in 34 local courts across the region,” Natalia Misko recalls.

On August 12, 2014, the President of Ukraine signed a law that allowed altering the territorial jurisdiction of courts in areas affected by hostilities. Following this, the High Specialized Court of Ukraine for Civil and Criminal Cases issued an order to change the territorial jurisdiction of courts in Crimea and the occupied territories of Luhansk and Donetsk Regions.

The jurisdiction of the Donetsk Court of Appeal (excluding the cases tried in Mariupol) was assigned to the Court of Appeal of Zaporizhia Region.

“After September 2014, the court had 115 judges and 100 staff members who were still working. Some of them relocated to Mariupol, while others remained in Donetsk. Additionally, the High Specialized Court hired judges for their advanced training, which was a common practice at that time. Most of the court staff were on vacation. I myself moved to Mariupol to work as a judge’s assistant,” recalls Natalia Misko.

Following its relocation to Bakhmut, the Donetsk Court of Appeal was able to resume its work on May 26, 2015, as per the order issued by the chairman of the High Specialized Court for Civil and Criminal Cases.

“The majority of judges with significant experience resigned for various reasons,” recalls Misko, adding: “In Bakhmut, the judges were mainly from that city, with some judges from Donetsk. Thus, a new team had to be formed in Bakhmut.”

According to the court’s chief of staff, almost none of the case files have been preserved.

“At that time, it was possible to salvage the cases, but unfortunately, there were no instructions from the court’s leadership to do so. However, in 2015, thanks to the Ombudsperson and the State Judicial Administration’s Territorial Department in Donetsk Region, we were able to secure up to a hundred cases from the Donetsk Court of Appeal. As far as I remember, court employees traveled to that territory and retrieved the cases,” Natalia explains.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the Donetsk Court of Appeal was forced to evacuate for the second time, this time including its Mariupol “branch”. To provide temporary accommodations, the Khmelnytskyi Court of Appeal allocated separate offices for the Donetsk Court of Appeal.

“My colleagues were very supportive and helped me with food and basic necessities. The judges started working remotely, and we registered all cases that arrived at the post office. We also cooperated with the prosecutor’s office and scanned all cases,” explains the court’s chief of staff.

According to Natalia Misko, compared to 2014 the preservation of case files in the court’s proceedings is somewhat better. She mentioned that on March 14, 2022, the court staff successfully moved all the equipment and the server from Bakhmut to the Khmelnytskyi Court of Appeal, and the cases remained in the proceedings of the judges who had tried them before the evacuation. However, the cases from Mariupol were not taken out in time.

Team of the Donetsk Court of Appeal in Bakhmut. Photo from the website of the State Judicial Administration

The court established an electronic document management system, scanning and storing case files in the Unified Judicial Information and Telecommunication System, making much of the information available in electronic format.

“If the case file has not been preserved, the procedural law provides for the possibility of reopening the case if there is a decision by the court of first instance. Furthermore, if the case file has not been preserved and the court decision has not been made yet, the party must file a new lawsuit with the court that has jurisdiction over the case. As a result, the court will consider the case from the very beginning,” explained the Chief Justice.

In March 2022, the Ukrainian Parliament amended the Law of Ukraine On the Judicial System and the Status of Judges to revise the territorial jurisdiction of courts where it was difficult to administer justice due to hostilities. According to the revised procedure, the High Council of Justice (HCJ) should transfer jurisdiction to the nearest geographically located court based on the proposal of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. However, since the HCJ was not functioning at the time, the Chief Justice issued such orders.

On July 22, 2022, the jurisdiction of the Donetsk Court of Appeal was assigned to the Dnipro Court of Appeal.

“Currently, the Donetsk Court of Appeal is not adjudicating any cases, and its judges have been reassigned to the Dnipro Court of Appeal. As a result, the judge assistants were dismissed from their positions, and the civil servants on staff have been placed on a layoff. In early March of this year, the central office informed us that there is no funding available, and therefore, the suspension of labor relations with the staff is being proposed,” explained Natalia Misko.

How many courts were forced to relocated

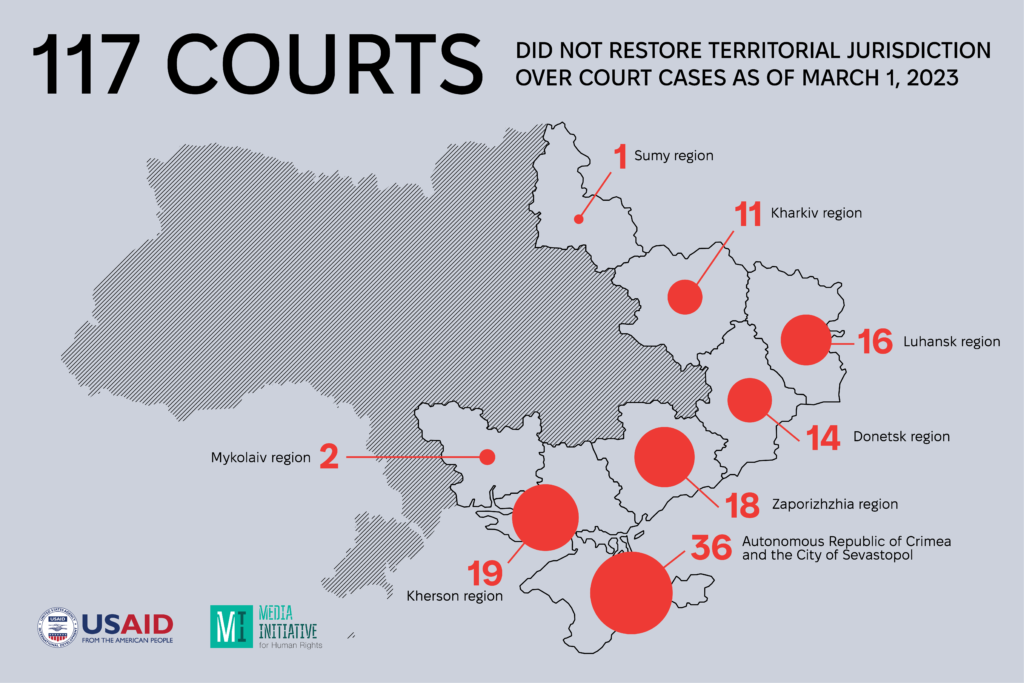

At the request of the MIHR, the High Council of Justice announced that due to the inability to administer justice during martial law, 171 courts changed their territorial jurisdiction. As of March 1 of this year, 117 of these courts were still unable to return:

Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol – 36 courts; Donetsk Region – 14 courts; Zaporizhia Region – 18 courts; Luhansk Region – 16 courts; Mykolayiv Region – 2 courts; Kharkiv Region – 11 courts; Kherson Region – 19 courts; Sumy Region – 1 court.

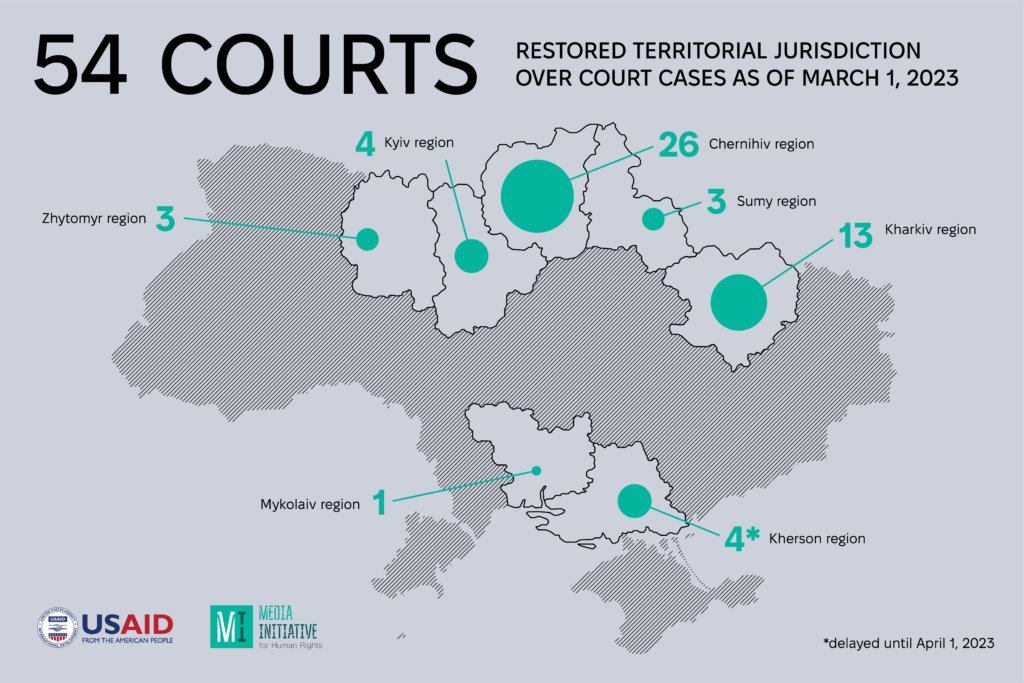

54 courts resumed their work: Zhytomyr Region – 3 courts; Kyiv Region – 4 courts; Mykolayiv Region – 1 court; Kharkiv Region – 13 courts; Kherson Region – 4 courts (deferred until April 1, 2023); Chernihiv Region – 26 courts; Sumy Region – 3 courts.

The Supreme Court’s website provides a summary table that lists all the courts which have had their territorial jurisdiction changed and, accordingly, courts that had new jurisdiction assigned to them.

There are varying opinions on the implications of such changes for court proceedings in courts with altered territorial jurisdiction.

Upon request by the MIHR, the Dnipro Court of Appeal, which oversees cases from the Donetsk Court of Appeal, has reported an increase in the number of appeals received. However, the workload of judges has not increased compared to 2021, as the court’s staff was expanded by transferring judges from Donetsk and Luhansk Regions.

Dnipro Court of Appeal. Photo courtesy of dp.suspilne.media

Throughout 2022, the Dnipro Court of Appeal received a total of 555 criminal proceedings and administrative offense cases, as well as 652 civil cases for consideration from local trial courts in Donetsk Region. Meanwhile, 202 criminal proceedings and 332 civil cases arrived from the Donetsk Court of Appeal.

The situation is different in the Bobrynets District Court of Kirovohrad Region, as it has been assigned jurisdiction over cases from the Snihurivka District Court of Mykolayiv Region, which was under occupation until the fall of 2022. Three judges administered justice in the Bobrynets court until November 2022, but now only two remain. The court’s workload has increased by 155 court cases in 2022, with a total of 1,534 cases received by the Bobrynets District Court of Kirovohrad Oblast during the course of 2022.

Bobrynets District Court. Photo from Facebook

How many displaced judges used the secondment procedure

The Supreme Court has launched a secondment procedure to ensure that displaced judges can continue to administer justice. The Decision of April 11, 2022 titled On Approval of the Indicative List of Courts to which Judges Are to Be Seconded identified several hundred courts where judges from territories affected by hostilities could be assigned. To do so, judges had to submit an application with justification and indicate three courts where they would prefer to work.

According to Natalia Misko, the chief of staff of the Donetsk Court of Appeal, some judges availed themselves of this opportunity.

“As of January 1, 2022, there were 34 judges in our court. Six of them applied for secondment and were sent to Khmelnytskyi, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Kharkiv in October. Later on, a new law was introduced that allowed judges to be transferred without their consent in case the territorial jurisdiction of a court changed during martial law. This law came into effect in July. The remaining judges were transferred to the Dnipro Court of Appeal,” stated the official.

The cases that were being tried by judges at the Donetsk Court of Appeal at the time were transferred to the Dnipro Court of Appeal.

“During the period when the Donetsk Court of Appeal was operating in Khmelnytskyi, new cases were distributed through the usual auto-distribution procedure. However, after the mechanism of judges’ secondment became operational, these cases were transferred to the Dnipro Court of Appeal. At that time, the Donetsk Court of Appeal had 230 criminal proceedings and 357 civil proceedings, while in Mariupol, there were 209 criminal proceedings, 184 civil proceedings, as well as administrative proceedings,” Natalia Misko says.

Olena Bodrova, a judge of the Snihurivka District Court in Mykolayiv Region, was one of the judges who participated in the secondment procedure. This court is based in Snihurivka.

“I lived in Kherson and commuted every day to work at the Snihurivka court. When the invasion started, I was at work, and it was very challenging to make my way back home that day. With my three children, I remained in the occupied territory for 41 days, while my husband was able to leave earlier as he is a police officer. I remember leaving the Snihurivka court with a colleague and passing through several checkpoints,” the judge recalls.

When she learned about the opportunity for judges to work in another region, she immediately filed an application.

“I chose to work in a court located in a safer region, thinking of my three children. After experiencing the occupation, I wanted them to live in peace. I started working at the Drohobych court in Lviv Region on June 1. My colleagues have been very supportive and even provided me with furniture. Although I have an assistant and a secretary, I had to purchase the equipment myself as budget funding is currently scarce, understandably,” says Olena Bodrova.

Snihurivka City Court after the city’s deoccupation. Photo courtesy of the Court of Appeal of Mykolayiv Region

The judge is currently presiding over new cases at the Drohobych court. She acknowledges that if the jurisdiction of the Snihurivka court is reinstated before she completes the proceedings for any of the cases in Drohobych, she will have to hand them over to another judge. Nevertheless, Judge Bodrova emphasizes that she is endeavoring to expedite the hearing of cases. As for the pending cases in Snihurivka, the judge explains that there were only a few by the end of 2021 and their disposition will be determined upon her return to her former workplace.

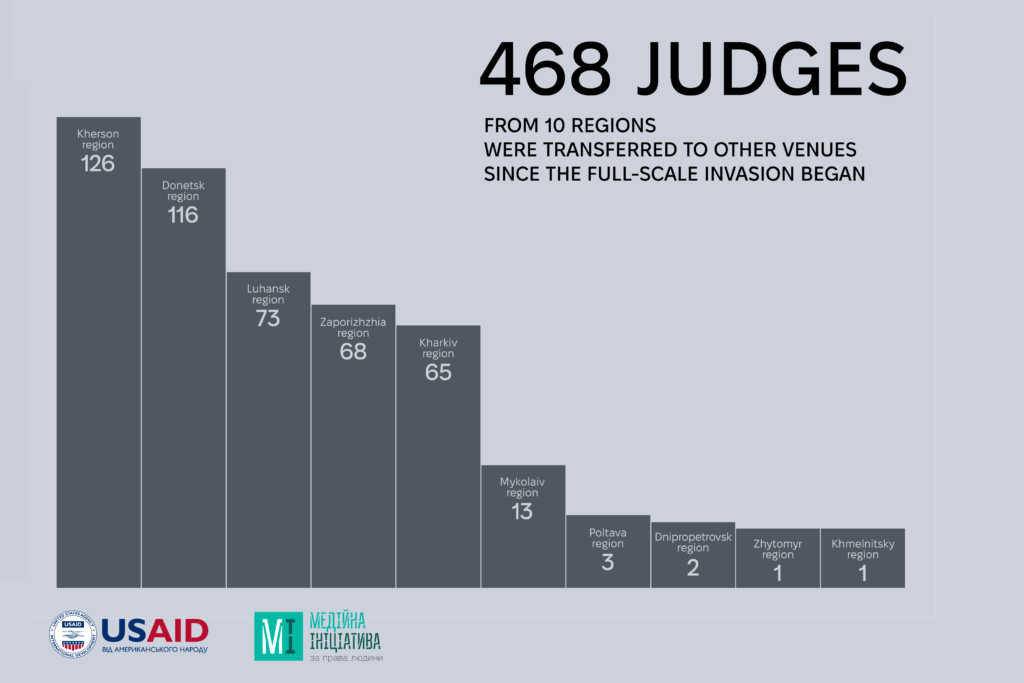

According to information provided by the High Council of Justice at the request of the MIHR, between February 24, 2022, and March 1, 2023, a total of 468 judges were seconded to different courts.

What is known about judges-collaborationists

In February 2023, the chairman of the High Council of Justice announced that the HCJ lacked precise information on judges who had colluded with the enemy and those who were unable to evacuate from the temporarily occupied territories. Similarly, the State Judicial Administration failed to provide such information upon request from Ukrainian News. Although the MIHR made inquiries to the Security Service of Ukraine regarding judges who had been notified of suspicion in cases of collaborationism, the special service ignored the request.

The Chesno movement has compiled a register of more than two hundred individuals who have defected to the enemy since 2014, including traitors among judges and lawyers. According to press releases and media reports from law enforcement agencies, Volodymyr Kupin, presiding judge of the Balakliya District Court of Kharkiv Region; Iryna Ukhaniova, presiding judge of the Vovchansk District Court of Kharkiv Region; and Ihor Kudriavtsev, judge of the Starobilsk District Court of Luhansk Region received notices of suspicion of high treason. Furthermore, Olena Ivanova, judge of the Novoaydar District Court of Luhansk Region, is being investigated for collaboration with the invaders. Reports also suggest that Oleksiy Turchenko, a former judge of the Central District Court of Mariupol, may be collaborating with the invaders.

This publication is a product of the Media Initiative for Human Rights, which is part of the project “Trials on the Events of the War in Ukraine: Monitoring, Coverage, Analysis”. The project is supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Justice for All Program. The opinions and views of authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of USAID or the US Government.

Anastasia Zubova, MIHR journalist