“I Cut Your Husband to Pieces”: In Kherson Region, Russian Occupiers Tortured a Teacher Because of Her Soldier Son

“Vladyslav — who is he to you?” At least six FSB agents stood in the yard of the Serdiuk family’s private home (the surname has been changed for security reasons).

One of the men was in civilian clothes. He held gray papers that appeared to be photocopied lists of Ukrainian servicemen.

“My son,” replied 58-year-old Liubov. She immediately understood that there was no point in lying to enemy intelligence officers.

“It’s good that you are not lying, because we already know he is your son,” they said, nodding approvingly.

The Russians kept questioning her: did she know where exactly Vladyslav was?

“No, I don’t know,” Liubov assured them. “My son said, “Mom, the less you know, the better you sleep.”

“That’s right,” the intruders agreed.

That ended the unwanted dialogue for Liubov.

It was not her first encounter with the occupiers — and it would not be the last one. But the next time, the Russians would not be so pointedly polite. A few months later, Liubov would be tortured by members of the Russian Armed Forces because of her son and her alleged transmission of coordinates to Ukrainian defenders. She shared her story with the MIHR.

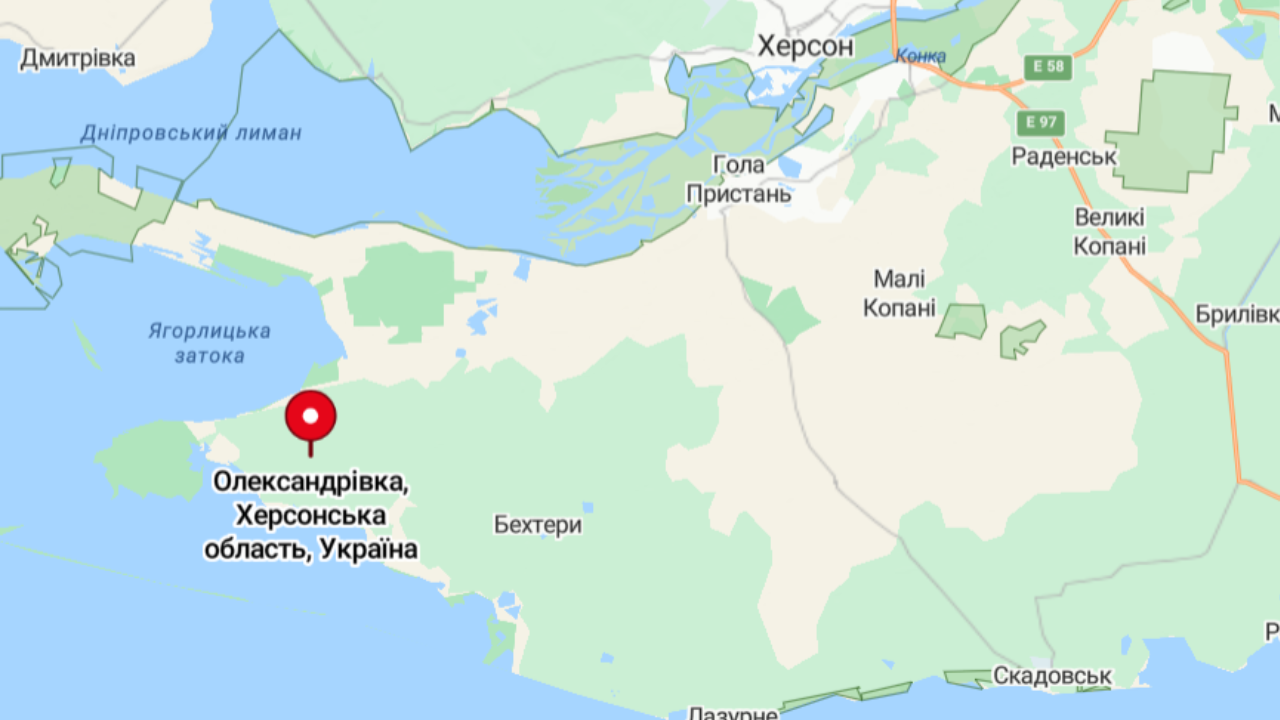

Before the full-scale invasion, Liubov Serdiuk was a Ukrainian language teacher and the principal of a school. She lived with her husband, Volodymyr, in the village of Oleksandrivka, Kherson Oblast. Both their children — a son and a daughter — serve in the military.

Liubov Serdiuk (surname changed for security reasons). Photo from Liubov’s home archive

At 4:45 a.m. on February 24, 2022, their son Vladyslav was called to his military unit. Scarcely had Liubov seen him off when several explosions rang out in the village.

“We were terrified because it was so close,” the woman recalls. “It takes just five minutes on foot through our vegetable garden to reach the military base. So, I quickly called my son, and he said he had just arrived and didn’t understand what was happening either. Later, Vladyslav called his parents back and advised them to take their grandchildren to the grandmother, who lived 50 km away in Stara Zburivka. The Serdiuks did as he advised and returned home the same day.

There were two military units in Oleksandrivka. The soldiers from both quickly mobilized and left.

“The unit where my son served was supposed to move to Pokrovka [a village in Mykolaiv Oblast, located on the Kinburn Spit],” Liubov explains. “But they didn’t make it. So, they just hid their weapons and equipment in the forest and returned to the village at night as ordered.”

On March 15, the occupiers began approaching the settlement. It was too dangerous for Ukrainian soldiers to remain in Oleksandrivka. They received orders to retreat through the Ivanivskyi Forest to Pokrovka, where a landing ship was to pick them up.

“They barely made it,” Liubov recalls. The Russians were hot on their heels, literally hunting them down.”

The Ukrainian defenders were lucky that day. On their way, they even managed to take the weapons they had hidden in the forest.

The ship with the soldiers aboard sailed toward Odesa, while Vladyslav’s parents stayed at home.

On March 18, Russian soldiers began going door to door in occupied Oleksandrivka.

“Who are you looking for?” Liubov asked Russian soldiers who had entered her yard. There were 12 to 15 of them.

“Nazis,” they replied angrily.

“Where do you see Nazis here?” she retorted. “This is a normal family with kids.”

“Believe us, we’ve found plenty already,” came the reply.

The soldiers checked the Serdiuks’ documents, searched their shed, and then left.

The next visit came in June. By then, Liubov had already heard that Russians were actively searching for Ukrainian military personnel and speaking with their families.

The FSB agents checked the Serdiuks’ phones and asked about their son. After Liubov assured them that she did not know his whereabouts, they said,

“If you get in touch with him, tell him to come back. We’ll find him a job here, and no one will punish him.”

Liubov stayed silent.

Tortures

In the fall of 2022, the Serdiuk couple was preparing to leave the occupied village. They had arranged for a driver to pick them up on September 30. The only available route to the Ukrainian-controlled territory was through Vasylivka in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. But the Russians closed that checkpoint on September 28, and the family missed their chance to leave. Their packed belongings remained untouched in the house.

On Saturday, October 1, there was a missile strike near the military base in Oleksandrivka. At around 2 p.m., a vehicle pulled into the Serdiuks’ yard.

Liubov was inside the house and, looking out of the window, saw a Russian soldier approaching the door. Before she could even react, he was already in the room, aiming a rifle at her.

“Get down, you b*tch, on the floor now!”

Startled and confused, she asked what had happened. Instead of answering, the soldier struck her hard in the jaw with the butt of his rifle. She collapsed.

“Speak, you f*cking Banderite! Who did you give the coordinates to?” the occupier snarled at her.

“What coordinates? I didn’t give anything to anyone!”

“Who did you pass information to? Where’s your son?” the serviceman kept asking.

“I don’t know where he is. And I didn’t give anyone anything,” Liubov protested.

“You Banderites should’ve been shot on the Maidan. It’s a shame I didn’t shoot more of you back then. We didn’t kill enough of you on the Maidan. We didn’t shoot enough of you there!” the soldier raged.

He started going through the Serdiuks’ laptop. But ahead of their planned departure, Liubov had carefully deleted everything — apps, messages, photos. She knew how carefully the occupiers searched gadgets at checkpoints, and did not want to take any risks.

Oleksandrivka on the map

However, that only enraged the soldier even more.

“Why is there nothing here?” he shouted. “Why did you delete everything?”

“I’m a teacher. I had lots of photos of kids in embroidered shirts. And I had greetings from friends in the Ukrainian language. I deleted it all because I was scared!” Liubov decided to tell the truth.

“Speak Russian, you b*tch!” he snapped. “I’m not going to waste time translating your nonsense in my head.”

Liubov tried to speak his language, but at one point she accidentally said something in Ukrainian — and immediately got punched in the face.

While one Russian was interrogating her, another was rummaging through the closets. The rest of the soldiers were outside with her husband.

One of them said to the woman,

“Now, I’m going to shoot your husband so that you start talking.”

Liubov panicked and pleaded,

“Please don’t hurt my husband — he had a stroke last winter, his heart is weak!”

The occupiers kept accusing her of passing coordinates to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

The soldier who had threatened to shoot Volodymyr came back inside.

“I’ve cut your husband into pieces,” he told her coldly. Then he pulled out a military knife and started jabbing its tip into her shoulder.

Liubov burst into tears.

“What do you want from me?” she asked her torturers through tears.

“Where’s your son? Who did you send the coordinates to?” they demanded. “If it wasn’t you, then tell us who it was.”

When they didn’t get the answers they wanted, the Russians ordered the woman to get ready. She barely had time to grab a sweatshirt from the chair.

Outside, she saw Volodymyr lying on the ground, surrounded by soldiers.

They shoved her into the vehicle, pulled a plastic bag over her head, and drove off.

“We drove for a long time, through fields,” Liubov recalls in her conversation with the MIHR. “Then I was transferred to another vehicle.”

At that moment, the plastic bag was replaced with a canvas sack. Along the way, she managed to lift the edge of it and saw a road. She realized that they were not taking her to Hola Prystan but somewhere farther away.

Camp “Slava”

When the vehicle stopped, Liubov — with the sack still over her head — was led into a building, seated on a chair, handcuffed, and left alone. She quickly realized that she was not the only one in the room. There were three other people there.

“What’s your name?” she heard a woman’s voice.

“Liuba.”

“Where are you from?”

“Oleksandrivka.”

“Oh, I also come from Oleksandrivka!” the stranger exclaimed happily.

She advised Liubov to try to pull her hand out of the handcuff. And she actually managed to do it. Liubov lifted the sack slightly from her head and saw the other captives. That is when she learned they had been locked in the laundry room of a children’s sports and wellness camp called Slava, located in the city of Skadovsk on the shore of the Dzharylhach Bay.

Children’s Camp “Slava” in Skadovsk. Photo from public sources

The day after her arrival at the Russian base, Liubov was taken for interrogation. They questioned her in a nearby garage. Once again, they asked about her son.

“We know he’s in Mykolaiv, shelling us,” they told her during the interrogation.

Liubov denied it, insisting that her son had never even been to Mykolaiv and had served in the same military unit his entire life.

From the conversation, she learned that the occupiers had no idea what position or rank her son held. So she told them he was a junior sergeant and a diesel mechanic.

The woman was interrogated by two Russians who removed the sack from her head during the questioning, so she was able to see them. The first one — Sasha (they addressed each other by first name) — looked to be under 30. He wore a balaclava, showing only his eyes, but his youth was obvious. The second one — Serhii — was older, around 50, with a short haircut. Both were dressed in Russian military uniforms.

Sasha asked most of the questions. Serhii appeared to be in charge of the tortures: he struck her on the head with a plastic water bottle and hit her over the left shoulder with a baton — so hard that it turned completely black and blue.

Later, the younger man brought in a pistol and pressed the muzzle against Liubov’s knee.

“You’ll be crippled for life,” he snarled. “I’ll finish you off right here.”

Then he pointed it at her face and fired next to her.

“I don’t know what exactly he fired — maybe some kind of gas,” Liubov recalls, “but I lost consciousness. I came to as they were pouring water over me.”

She was wearing light summer pants, which soaked through instantly, and she began to freeze. Meanwhile, her torturers called in a medic, who checked her blood pressure and gave her a pill.

They also threatened to cut off her ear and “send it to her son by mail.”

The occupiers had Liubov’s mobile phone, and she feared that they might call her son. Later, after her release, she learned that her children had been informed of her abduction right away.

“My son and his commanders knew anything was possible,” she told the MIHR. “They knew my phone had been taken. So, they were prepared for phone calls, for provocations. But of course, I was terrified at the time.”

The second interrogation was conducted by the same soldiers who questioned her again about Vladyslav.

“So, are you ready to tell the truth?” one of them asked, watching her intently. “If not, we’ll take you to Crimea. They’ll deal with you there, and you won’t come back home.”

This time they also asked about her daughter. Liubov told them that she had left for Poland to work before the full-scale invasion.

The questioning did not last long. Afterwards, she was returned to the laundry room with the other prisoners and was not interrogated again.

On October 5, she was taken out, put into a military vehicle, and driven away. She was left to spend the night in the village of Hladkivka. That evening, she became ill — her blood pressure spiked again — and a medic was called.

She was led into a shed for the night, where there was only a wooden bench. They did not remove the sack from her head, but after the soldiers left, she pulled it off herself. Later, someone brought her dinner — pasta with sausage. It was the first time that she had been fed during her captivity.

Despite her hunger, she could not eat.

When it got dark, a guard came back to the shed.

“Liubov, why aren’t you eating?” he asked when he saw the full plate.

“Sorry, I just don’t feel like it,” she answered politely.

He then asked whether any relatives or friends could come to pick her up and take her home.

“Who would come for me?” Liubov replied sadly. “And at night, when the curfew is in force? Who would dare?”

“Then you’ll have to stay overnight,” the occupier said. “We’ll take you home in the morning.”

He also brought her a blanket and a pillow.

Why is there no roof?

In the morning, Liubov was put in a car and taken away again. When they entered Oleksandrivka and stopped near her yard, the same Russian soldier who had spoken with her the night before asked in surprise,

“Is this… your house?”

But Liubov could not see anything — her head was tightly wrapped in a hood.

“Why is there no roof?” the occupier continued.

“What do you mean, no roof?” the woman gasped.

“You can take off the hood now,” he allowed.

Only then did Liubov see that almost nothing was left of her house — just charred walls and ashes.

She walked around the ruins in a daze, with only one thought pounding in her head: “Where is my husband?”

“I thought they had burned him alive in the house,” she says to the MIHR.

Meanwhile, the Russian soldier asked if she had anyone she could stay with.

“The godmother of my child lives two houses down,” Liubov replied in shock.

The Russians escorted her there.

“Where’s Volodia?” she asked immediately.

“He’s here, at Vlad’s place,” the godmother nodded toward the Serdiuk son’s house.

When the couple finally reunited, the Russians who had accompanied Liubov questioned Volodymyr about what had happened to their house. Only then did they finally leave the Serdiuks alone and drive off.

Volodymyr looked good, but it turned out that the Russians had stabbed him in the back several times and beaten him with rifle butts.

On the day Liubov was taken, the Russians came back to the Serdiuks’ house late that night.

“Come out,” they told Volodymyr. “Do you have anywhere to stay?”

“What’s going on?” he asked tensely.

“We’re going to set up an ambush here. You’ve got visitors coming, and we’ll be waiting for them.”

“Who would be coming to visit us?” he tried to protest. But it was no use.

Now Liubov believes that someone in the village had tipped the Russians off — not just revealing that their son was in the military, but also spreading lies about some supposed “visitors”.

That night, Volodymyr went to sleep over at the place of the godparents of his child. In the middle of the night, he heard a strange cracking sound, then a blast.

“Maybe another strike?” he thought, and ran outside to check.

But it was their house on fire. The Russians had set it ablaze, then fired on it with heavy equipment, blowing the gates off completely.

Volodymyr tried to put out the fire, but it was no use. The man spent the night in a shed. In the morning, he saw two Russian soldiers enter the yard and take photos of the burned-out ruins.

The next day after Liubov returned home, the couple left Oleksandrivka. Her friends brought her some clean clothes because she had nothing left. First, they stopped in Stara Zburivka to see Liubov’s mother. Eventually, their children found a driver, and on October 20, the family left the country via Russia, later returning to Ukrainian-controlled territory.

When they crossed the Russian border, Liubov asked a foreign border guard if it was already Latvia.

“And when she said yes, I gave them [the Russians] the finger several times,” Liubov laughs.

Author: Yevheniia Korolova, the MIHR journalist

This article was published with the support from the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its content does not necessarily reflect the official position of the EED. The views or opinions expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the author(s).