Kherson Deputy Karamalikov is on Trial for High Treason—during the Occupation, He Handed over a Detained Pilot to the Russians.

In Kryvyi Rih, Illia Karamalikov, a Kherson deputy from Ihor Kolykhaiev’s party “We are to Live Here!” is on trial. According to the investigation, at the start of the occupation, he handed over a Russian pilot detained by locals to the Russian National Guard. This is considered high treason. Karamalikov acknowledges that he released the soldier but insists that he did not do so because of pro-Russian views. His story was published by The New York Times, his friends are composing songs about him, and he has already written a book about his life, the trial, and the occupation.

The trial has been ongoing since October 2022. During this time, numerous witnesses were questioned, evidence examined, and petitions considered. After the witnesses are heard, Karamalikov will have the floor in court. He faces either 15 years in prison or life imprisonment.

After attending two court hearings, speaking with Karamalikov and his lawyer, analyzing information in the Kherson media, and reading the book, the Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) accounts for the trial’s progress.

A Businessman, Philanthropist, and Quaker

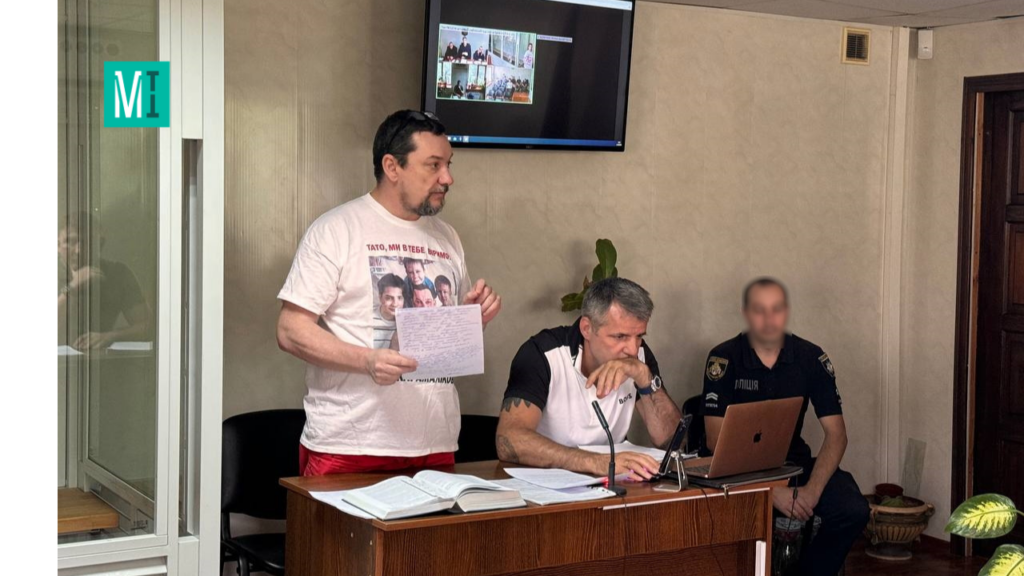

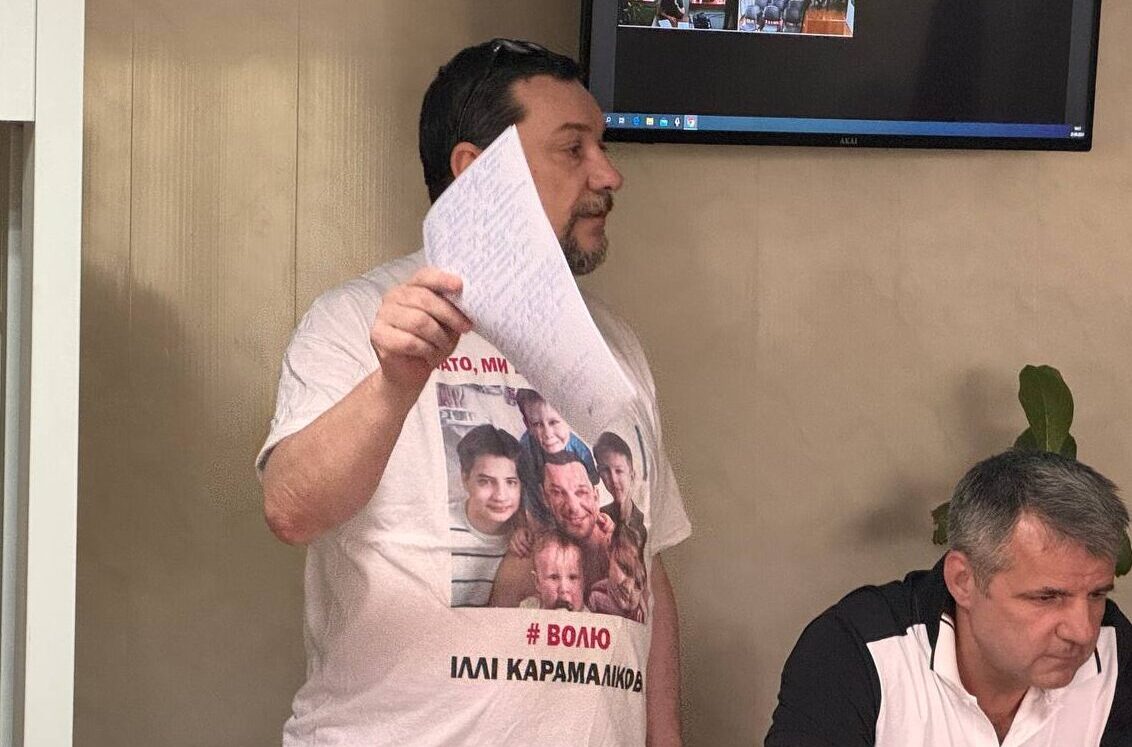

“Dad, we believe in you. Free Illia Karamalikov,” reads the inscription on the T-shirt Illia Karamalikov wears as he enters the courtroom of the Zhovtnevyi District Court. The T-shirt also features a photo of his children. The case is being heard in Kryvyi Rih because the Kherson SSU was operating there when the proceedings were initiated. The convoy escorts Karamalikov to the table. At the lawyer’s earlier request, the court allowed Karamalikov to sit with his defense attorney instead of in a holding cage.

Defense attorney Mykhailo Velychko also enters the courtroom. He arranges his work materials, turns on his laptop, and sets up his smartphone on a tripod to stream the proceedings on his social media.

The prosecutor, who also has a stack of papers, sits at the opposite table. A law student observes the courtroom. The Verkhovna Rada Commissioner for Human Rights representative follows the proceedings online.

— You can take a comment from Illia during the break — the lawyer says while waiting for the judges to arrive. — Such an exclusive opportunity is only available in court.

Despite the attention from foreign media, no journalists attended the recent hearings, so they are unlikely to miss this chance.

Karamalikov is 53 years old. A businessman and politician, he was born in Russia and lived in Kherson. At the time of the full-scale invasion, he owned two popular city nightclubs and a significant amount of real estate. He was also the founder of several businesses and a charity foundation. He called himself the pastor of a religious organization, the Quaker Judas. This Protestant denomination, Quakerism, is known for its pacifism and humanitarianism.

The Kherson publication MOST reported that in the late 1980s, Karamalikov was convicted of fraudulent currency transactions. Soon after, he changed his last name from Voronov to Karamalikov. He explains the reasons for this in his book, published on Google Drive with the court case materials. He adopted his wife’s last name to express his feelings toward his father, who abandoned him in childhood and never visited him, not even in prison. At the same time, he divorced his wife six months after the birth of their child because he “was unprepared for family life.”

After serving his sentence, Karamalikov opened grocery stores and expanded his business. He also sued “Khersonoblenergo” for an electricity discount, claiming that a religious organization was registered at his nightclub.

The accused, Illia Karamalikov, calls himself a Quaker, emphasizing that Quakers always tell the truth. Photo: Anastasiia Zubova

Karamalikov entered politics in 2006 as part of the team of the then-mayor of Kherson, Volodymyr Saldo, who has since sided with RF. He later became an assistant to a member of parliament from the UDAR party, ran for the Kherson City Council under the Petro Poroshenko Bloc, and in 2020 became a deputy from Mayor Ihor Kolykhaiev’s party “We Are to Live Here!”

Motions

After a few minutes of waiting, the panel of judges at the Zhovtnevyi District Court begins the hearing.

—Illia Mykhailovych, I saw your motions and had no doubt they would be filed. But we determined to consider temporary access matters today — the presiding judge, Ihor Chaikin, addresses the defendant businesslike before adopting a more personal approach. — Unless your motions state that you are dying, we will first proceed with the planned issues and address everything else afterward. So, you may briefly outline the titles of your motions.

—Your Honor, I won’t read it aloud — Karamalikov says, though he is unlikely to be concise. — I’ll only say that this motion is probably the most important one in the entire history of our court hearings because I’ve made nearly 400 inquiries to all government authorities about what civilians in an occupied city were supposed to do with a wounded prisoner of war. But no one has given me an answer.

— Is that all, Illia Mikhailovich? — The judge interrupts. —Then, please sit down.

The detention of Illia Karamalikov. Photo: SSU

Karamalikov’s defense lawyer, Mykhailo Velychko, takes the floor. The publication MOST reported that Velychko previously led the city organization “Stop Corruption.” This NGO was accused of bias, and its members accompanied the now-deceased Illia Kyva during his visits to Kherson, allegedly to fight corruption. At this hearing, Velychko filed two motions.

In the first motion, Velychko requested access to the SSU documents that investigators relied on to obtain court approval for covert investigative actions against Karamalikov. He argued that the investigators’ request to the court referenced alleged offenses by the deputy, information supposedly obtained during counterintelligence activities. Velychko claimed that information was absent from the case files and asked the court to retrieve it.

The second motion sought access to data from a mobile operator to determine the location of Karamalikov’s phone in April 2022. Velychko aims to use this information to prove his client’s unlawful detention.

Law enforcement officers detained Karamalikov on April 14, 2022, at a checkpoint in Bashtanka, Mykolaiv region, as the deputy was leaving Kherson. On Velychko’s account, SSU officers held Karamalikov extra-judicially in Kryvyi Rih for a week. The Saksahanskyi District Court imposed a pretrial detention measure and ruled to confiscate his phone only on April 20, 2022.

Velychko explains:

— My client told me that during his unlawful detention at the SSU premises and the lie-detector interrogation on April 18, the investigator turned on his phone, and it connected to the network. Access to the operator’s data will help determine the phone’s location at that time.

Andrii Bezkrovnyi, a Kherson Regional Prosecutor’s Office’s prosecutor, objected to the motions, arguing that Velychko could have filed them during the pretrial investigation and that they were not related to the charges.

After hearing the positions of both sides, the court retired to the deliberation room.

Prosecution and Defense

While the panel deliberated, Karamalikov was eager to talk about the case.

— How do you explain this case? — I asked.

— I am accused of handing over a soldier, — he says, switching to Russian. — But what’s it about? Today, I prepared a motion regarding the procedures needed to be followed according to the Geneva Convention for prisoners of war.

On Karamalikov’s account, he urged people to self-organize in the early days of the full-scale war. This led to the formation of a “people’s guard” that patrolled the city, delivered food, and stopped looting.

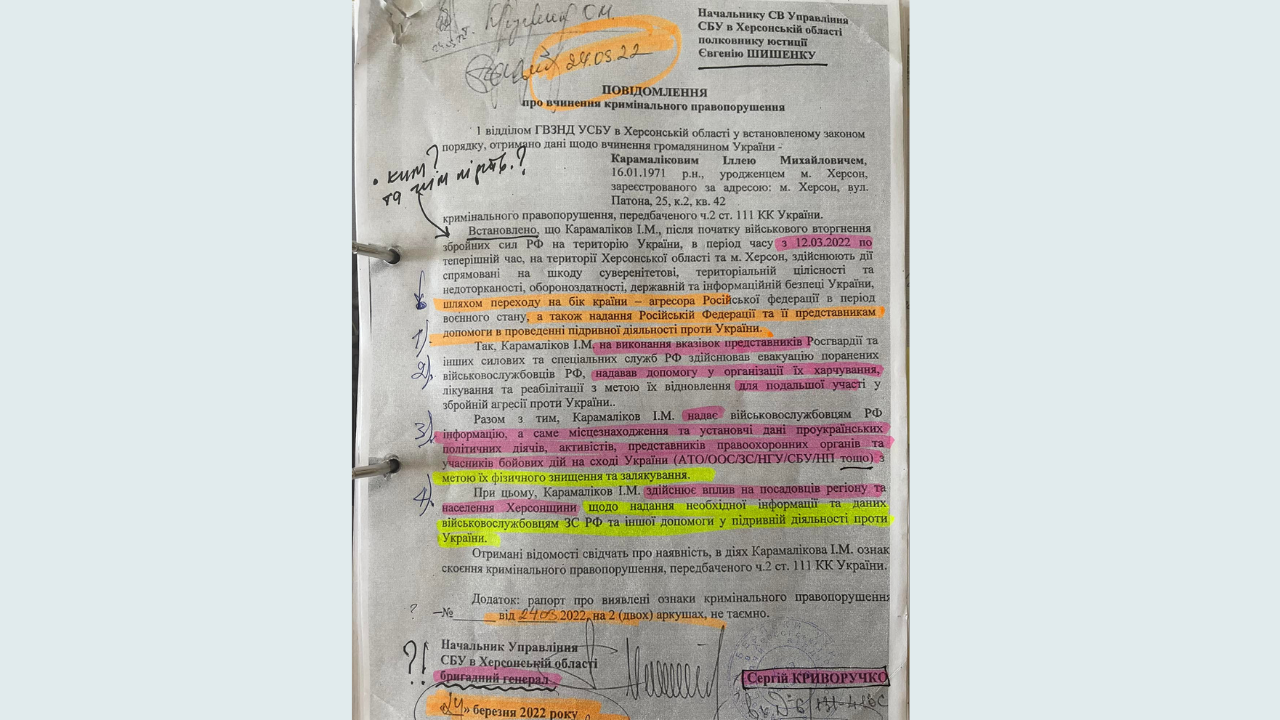

Suspicion of Illia Karamalikov. Photo: Facebook page of lawyer Mykhailo Velychko

The media and social networks are full of posts and videos from that period about the work of the “public order squad.” Karamalikov also commented on the situation in the city to both Ukrainian and foreign media.

— We hid the guys from the 80th Brigade, which is currently fighting in the Kursk region, — Karamalikov recalls the first weeks of March. — We kept weapons. The vigilantes were transporting our soldiers by boats.

To support his words, Karamalikov shows a letter signed by the former commander of the 80th Separate Airborne Assault Brigade, Emil Shuklinov, in which the letter thanks Karamalikov for hiding Junior Sergeant Maksym Shevtsov. In 2023, Shevtsov received an award from the President of Ukraine. Karamalikov explains he began hiding Ukrainian soldiers from the early days of the full-scale war. This, along with his six children, pets, and subordinates, prevented him from leaving the occupied area.

Karamalikov recounts that on March 15, the “vigilantes” detained a wounded Russian helicopter pilot in Kherson, who was coming from Chornobaivka. Since Karamalikov was seen as a leader, they immediately called him and asked what to do with the soldier. He nervously recounts:

—Look, Ukrainian soldiers are hiding in my house. There is no way to escape from the occupied city. This is not the first week of occupation.

Velychko interrupts:

—Take your time, don’t make a mess. Just speak calmly.

Karamalikov continues:

— At that moment, we find a Russian soldier who doesn’t resist, surrenders his weapon, and says, “Do whatever you want with me. I’ve had enough of fighting.” We fed him and bandaged his head wound, not knowing what to do.

They couldn’t transfer him to the Ukraine-controlled territory, as the Russians would have detected him at the first checkpoint. Karamalikov didn’t allow killing the pilot.

— When the Russian soldier was captured, about 40 vigilantes already knew about it. You know that biblical story about Moses, who killed an Egyptian when no one was watching? Well, the next day, everyone already knew it was him. The same risk existed here — someone could have told the Russians. We had to divert suspicion away from the guys.

Karamalikov recounts he asked Anatolii Khomenko, the deputy legitimate mayor, for advice. Soon after, in March, Khomenko died, and his son later became the occupying head of Oleshky.

Velychko takes over to tell the story:

— Illia calls Khomenko, who was in charge of cooperation with law enforcement. Khomenko tells Ilya, “Hold the prisoner for now, I’ll call you back.” He talked to the SSU officers and passed on the recommendation to hand over the pilot to the Russians to avoid putting the Ukrainian soldiers hiding at Karamalikov’s place in danger. Accordingly, Illia calls the Russians without any secrecy and informs them about the prisoner.

On the prosecution version, in March 2022, Karamalikov was recruited by Oleksandr Naumenko, a Russian National Guard officer with the call sign “Alpha.” In occupied Kherson, he was in charge of the Russian National Guard, which was dispersing rallies and torturing people. At the trial, Kherson police officers confirmed they had seen Naumenko giving orders to beat them. “Alpha” was the one Karamalikov eventually called regarding the pilot. This phone call, apparently intercepted by Ukrainian counterintelligence, became one of the key pieces of evidence in the case. However, Velychko argues that Karamalikov was forced to communicate with the Russian National Guard to secure the release of detained vigilantes.

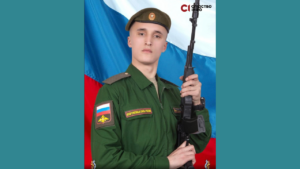

Oleksandr Naumenko, also known as Alpha. Photo: Myrotvorets

—We listened to this recording in court. Illia doesn’t deny the contact. But, first of all, he was following Homenko’s instructions. Secondly, the context of this call is crucial, — Velychko explains.

His explanation suggests that “Alpha” ordered Karamalikov to bring the pilot to the commandant’s office. However, the deputy did not want to be seen there, so he agreed to keep the soldier at his place overnight.

Karamalikov himself says that after that conversation, he decided to find ways to avoid handing over the prisoner. However, he eventually released him, but not to the Russians:

— In the morning, I handed over the pilot to Valerii Kuleshov, who came for him on Homenko’s instructions. He’s a local blogger. After that, I went to the Russians and told them their pilot had escaped.

Kuleshov is a former law enforcement officer who, even before the full-scale invasion, was involved in political provocations alongside Stremousov. Since 2022, he had been streaming from battlefields and volunteering in the occupied areas at the office of Kolykhaiev’s party. Kuleshov was a member of the NGO “Kherson Fortress.” The other co-founder of this organization was Serhii Torbin, the organizer of the attack on activist Kateryna Handziuk, who died after the assault. In April 2022, Kuleshov was shot near his home. Subsequently, the occupiers opened a kind of memorial in Henichesk, where Kuleshov’s name was listed among others. However, he never publicly declared his allegiance to Russia during his lifetime.

Velychko explained that during the trial, a witness was questioned who had worked at Kolykhaiev’s office at the time. The witness testified that he had overheard Khomenko instructing Kuleshov to go to Karamalikov’s place and retrieve the Russian soldier.

Despite his lawyer’s request, Karamalikov speaks nervously:

— Do I admit it? Yes, I acknowledge that we—civilians in the occupied city—were hiding Ukrainian soldiers and weapons. We fed thousands of people whom the Ukrainian authorities abandoned without announcing any evacuation. The SSU officers who are now accusing me fled the same way.

The notice of suspicion against Karamalikov was signed on March 24, 2022, by Serhii Kryvoruchko, then the head of the Kherson SSU. In April, Zelenskyi declared Kryvoruchko a traitor and stripped him of his general rank. However, allegedly, he was not officially informed of the suspicion. Although Kryvoruchko no longer holds an official position, he remains at the disposal of the SSU.

Karamalikov continues, “The Geneva Conventions stipulate that a prisoner of war must be transferred to a camp as soon as possible to ensure their rights. A Ministry of Defense Order dated 2017, “On the Approval of the Instruction on the Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Norms in the Armed Forces of Ukraine,” also states that the military unit that captures a soldier must immediately transfer them to a prisoner-of-war camp. If such an opportunity is unavailable, they must be released.”

The deputy explains that, while in detention, he was interested in legal norms and sent inquiries to government bodies asking for clarification on how civilians in an occupied city should act when detaining a Russian soldier. As he did not receive any answers, he studied the legislation himself.

— There was a post on your social media stating that you propose to exchange yourself for Ihor Kolykhaiev, who is currently in Russian captivity, — I clarified.

— If my country considers me a traitor for following the Geneva Conventions, exchange me for Kolykhaiev then.

— You’d go to a Russian prison? That doesn’t scare you?

— If I’m handed over to Russia tomorrow, Israel will be able to step in for me, — Karamalikov explains. — Ukraine doesn’t recognize dual citizenship. But in Russia, I’ll be considered a citizen of both Ukraine and Israel. I think it’s a reasonable step — to save one more person who suffered for Kherson. And secondly, Ukraine has destroyed my life. For saving its soldiers and following the Geneva Conventions, I’ve been held in prison for two and a half years. My children are now struggling in Bulgaria, working in hotels.

— You mean, if you’re exchanged to Russia, you don’t plan to stay there?

— Of course not. I’ll be honest—I’m a Quaker, and Quakers never lie. Here’s my plan: if I’m handed over to Russia, within a week, Israel will take me in. I’ve already spoken to the embassy. But for now, they can’t intervene because I also hold Ukrainian citizenship.

In addition to the episode with the Russian pilot, the investigation alleges that Karamalikov urged colleagues and officials to collaborate with the Russians, organized accommodation for Russian military personnel, and provided information about pro-Ukrainian politicians, activists, law enforcement officers, and ATO veterans.

On Velychko’s account, two witnesses allegedly made these statements over the phone, but no recorded conversation exists. They were also not questioned in court because they are currently in occupied territory. The prosecutor has not dismissed their testimony, so the court tasked the SSU with locating them.

Karamalikov asserts that no one in court has confirmed that he encouraged anyone to collaborate with Russia. One court ruling mentions that a Kherson City Council deputy, seemingly invited by the defense attorney, testified that at the beginning of the occupation, Karamalikov helped local residents and was a patriot of Ukraine.

Another argument in the indictment claims that during the occupation, Karamalikov assisted propaganda media in creating the narrative of the “Russian world” arriving in the Kherson region. However, the MIHR could not find any public interviews or videos of Karamalikov in which he supported Russia.

At the same time, Karamalikov covered the life of the occupied city on his page, presenting himself as a correspondent for the “Kherson Bulletin New.” This Facebook page was coordinated by blogger Hennadii Shelestenko, who was accused of treason in March 2022 for pro-Russian propaganda. In September 2024, Shelestenko was convicted in absentia of collaborationism based on his publications on the Russian website “Politnavigator” and his participation in pro-Russian rallies.

Andrii Bezkrovnyi, Prosecutor of the Kherson Regional Prosecutor’s Office. Photo: Anastasiia Zubova.

Judging by the Bulletin’s posts, Karamalikov and Shelestenko have been acquainted for a long time. Even before 2022, Karamalikov’s statements about his deputy’s activities were reposted on the page.

However, unlike Shelestenko, who appeared with Kyrylo Stremousov at a small pro-Russian rally on March 13 and spread pro-Russian propaganda, Karamalikov covered events neutrally or from a pro-Ukrainian perspective. On March 3, he published a video from a pro-Ukrainian rally; on March 13—an interview with Mayor Ihor Kolykhaiev about the dire situation in the city; and on March 17, he showed the Ukrainian flag above the city council, claiming “Everything will be Ukraine.” At the same time, in one of his streams, he doubted that the Russians had already detained 300 people.

In numerous reports by both Ukrainian and foreign media, Karamalikov, in the early days of the full-scale invasion, talked about the city’s occupation, affirmed that Kherson is Ukraine, and participated у in pro-Ukrainian rallies.

In April, Karamalikov eventually left Kherson after Russian forces raided his nightclubs. Russian propagandists published a video about an “outpost of nationalists” in Karamalikov’s club, showcasing Ukrainian flags and weapons they supposedly found at the premises. While Karamalikov was attempting to leave, he was detained in the Mykolaiv region and later taken into custody.

The prosecutor refused to comment on the case, explaining that he had previously expressed his position in court and had no desire to comment on “every unbelievable story” presented by the defense.

Meanwhile, the court granted only Velychko’s second request for access to the mobile operator’s data.

The Book in the Pretrial Detention Center

At another hearing, the court considered the MIHR’s motion for a broadcast.

As at the previous session, a law student attended. He had his internship at the court when he heard about the case. Since then, he has been following the process out of professional interest.

— What was your impression of the case? — I inquired.

— You know, I’ve been following the trial for ten months now, — he remarked. — Throughout this time, the defense has been proving the defendant’s innocence, although it’s the prosecution’s job to prove his guilt. All the witnesses, including those for the prosecution, haven’t said anything that indicates the defendant’s guilt. On the contrary, they speak well of him.

While everyone was waiting for the decision regarding the broadcast, I spoke with Karamalikov again about his book.

— How did you manage to write a book in prison conditions? — I wondered.

— Well, I just wrote it by hand. Then, the girls typed it out and translated it. After that, I corrected the typed version. They’re supposed to pass me the text again for revision. I have an illegible handwriting — Karamalikov explains.

Currently, the book exists only in an online format. The publishing houses Karamalikov approached refused to print it. His nomination for the Shevchenko Prize was also unsuccessful. He believes the reason for this is the description of the alleged crimes the Security Service of Ukraine committed against him.

I briefly reviewed the book. Besides Karamalikov’s biography, which describes his adventurous youth, life in the 1990s, and his rise as a businessman, the book outlines his views on politics and history. The message is that Ukraine and Russia, as members of the same family, each have their own truth that lies somewhere in between. Essentially, Karamalikov equates the victim and the aggressor. Almost echoing Putin’s claim that Lenin created Ukraine, he states that only under the communists did Ukraine acquire statehood and borders. He cannot explain why the current phase of the war began but says both sides are to blame in the conflict.

Ultimately, the court postponed the hearing to arrange a broadcast for the next session.

What does IHL say?

Anna Rassamakhina, a lawyer and expert in International Humanitarian Law (IHL) at the MIHR, comments on the compliance of the accusation with IHL. She explains that a combatant becomes a prisoner of war only when captured by an entity representing the state, such as the armed forces.

—Private individuals, in this case, paramilitaries and volunteers, cannot take anyone prisoner. This is because captivity is a special legal status, subject to many requirements of the Geneva Conventions, — Rassamakhina explains.

The captured pilot laid down his weapon because he was wounded and could no longer actively participate in combat. The accusation asserts that Karamalikov handed him over to the Russians so that he could return to fighting.

—But if this goal is being accused, it needs to be proven,— Rassamakhina emphasizes. —However, when a person who doesn’t belong to an armed formation provides medical assistance to such a detainee or hands him over to someone, it cannot be considered a crime. At least not in the formulation we see in the indictment.

This material was made possible by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the generous support of the American people through the Recovery and Accountability through Human Rights Project (PravoZahyst).