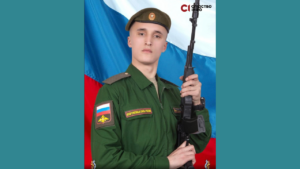

One Year Since Russian Prisoner of War Kartashev Faced the Trial: Irpin Court Makes (No) Progress in Considering the Case

Nikolay Kartashev, a 22-year-old Russian serviceman from Rostov Oblast, is charged with killing a civilian during the occupation of Bucha in 2022. He is accused of violating the laws and customs of war. This is one of the few war crime cases that are tried not in absentia, that is, Kartashev is in the dock. According to the MIHR, there have been only ten such cases in total over two years. Contrary to the expectation of a proper consideration of the case, the opposite is true — the court has not yet moved on to considering the evidence, and the hearings have been constantly postponed. This indicates a dangerous trend in justice administration. You can learn more details about the case in the analytical article of the MIHR.

Key facts of the case

In 2022, Nikolay Kartashev, a member of airborne troops of the Russian Federation, participated in occupation of the Kyiv region. One day, he, together with other Russians, was moving in convoy of vehicles along Vokzalna Street in Bucha. His commander ordered to shoot “everyone clothed in black”. The investigation revealed that Kartashev had shot a supermarket security guard, who was a civilian. In 2022, Nikolay was sentenced for desertion in Russia, but later he apparently returned to the front. Kartashev was taken into captivity by Ukrainian troops in February 2023 in the Kharkiv region — it is still unknown whether there was a case against him at that time. He is currently held in a prisoner of war camp in Lviv Oblast.

Kartashev’s case has been considered by the Irpin Court for a year. It is currently being heard on its merits, but the court has not yet moved on to examining the evidence.

Five postponed hearings

The indictment was submitted to the court on September 30, 2023. At the preliminary hearing, defense attorney Artem Halkin, appointed by the Free Secondary Legal Assistance Center, asked to return the indictment to prosecutor Mykhailo Nechytaliuk. He noted that the document lacked the facts pointing to Kartashev’s admission of guilt during the pre-trial investigation, his repentance and active assistance in solving the crime.

On November 2, 2023, the Irpin City Court concluded that the indictment should be returned to the prosecutor due to a violation of the presumption of innocence principle — it contained data on Russians who probably had committed the crime together with Kartashev. The prosecutor filed an appeal as he believed that the indictment contained only facts of the case. The appeal succeeded.

The court continued to consider the case in the spring of the following year — the hearing was scheduled for May 9, 2024. Kartashev was transported from the prisoner of war camp. That day, the courtroom was filled with journalists and members of the public.

The prosecutor asked to hold a trial based on the indictment that accused Kartashev of killing a civilian during the occupation — par. 2 of Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. The murdered man has no relatives, so there are no victims in the case. The prosecutor decided not to request a preventive measure as Kartashev has the status of a prisoner of war and there is no risk that he will go into hiding.

Russian serviceman Nikolay Kartashev behind glass in the courtroom. Photo: MIHR

The prosecutor, referring to the need of respecting honor and dignity when treating prisoners of war, asked not to record the trial. This is not typical. Such issues are usually raised by the defense. Presiding judge Yana Shestopalova stressed that the defendant had the right to have his trial recorded, and Kartashev’s defense attorney noted that he would agree on a position with him before the next hearing.

However, Halkin did not appear at the hearing on August 8. The court asked about the possibility to proceed with the consideration. Kartashev answered, “We can do without a lawyer.” But the court noted that since he was a citizen of another country and was charged with committing a particularly serious crime, the hearing could not be conducted without a defense attorney. The next hearing was scheduled for September 10.

On September 10, Kartashev was brought to the court again. As the hearing was delayed, the journalists, waiting for it to start, left. However, the court hearing did not take place once again. Halkin filed a motion to appoint a new defense attorney for Kartashev, since he lived in Kyiv and could not travel to Irpin to participate in hearings.

The judge postponed the hearing until October 3, but the panel of judges failed to meet that day — so the hearing has been postponed for the fifth time. The date of the next hearing is unknown.

System as it is

Lawyer and expert of the MIHR Anna Rassamakhina notes that the case of Kartashev exposes systemic shortcomings in the Ukrainian judicial system.

“The vast majority of cases are heard in absentia, that is, in the absence of defendants,” says Anna Rassamakhina. “If a case is heard in the presence of a defendant, the court has an opportunity to examine their testimony and arrive at a reasoned decision, which will come into force. The judgment can be implemented.”

However, the lawyer notes that sentences passed in cases heard in absentia, although they have come into force, can be reviewed by the court if the convicted person appeals them. However, this is just a theory, because so far Russian soldiers have not filed appeals to review sentences in absentia, that is, the position of Ukrainian courts on this matter is unknown.

Court hearing of the Kartashev case. Photo: MIHR

“Considering cases in absentia is a special tool. But it became a common practice during the Russo-Ukrainian war,” says Anna. “It is obvious that cases heard in the presence of defendants should be considered as efficiently as possible. There are few of them so this can be done despite a significant workload on courts.”

She adds that the reasons for postponing the hearings of the Kartashev case (the lawyer did not arrive, judges are busy, etc.) are also true for other cases. At the same time, the MIHR expert believes that it is unacceptable when consideration of the case was suspended for seven months due to the unreasonable return of the indictment to the prosecutor.

All this indicates the same problems of justice that one encounters while handling cases with Russian soldiers charged with war crimes and sitting in the dock and cases heard in absentia.