Sailors from the vessel “Donbas”: An unknown page of the heroic defense of Mariupol

This story began in 2014, when young cadets, who had not betrayed their oath, sang the Ukrainian anthem on the Nakhimov Naval Academy parade ground in Sevastopol. They were singing while the rest of the traitors and the occupiers were replacing the Ukrainian flag with the Russian flag on the flagpole. Eight years later, the former cadets, now sailors, stood up to defend Ukraine. In Mariupol. Side by side with the National Guard and the Azov Regiment.

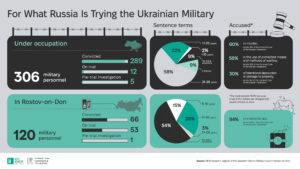

During the defense of Mariupol until mid-May last year, over 40 sailors from the crews of the search and rescue vessel “Donbas” and the small armored artillery boats “Kremenchuk” and “Lubny,” which were defending the city and its port, were captured by Russians. Most of them are still in captivity.

The man who wants to see his son

Crimea, 2014. Dmytro Klymovych, a second-year student at the Naval Academy named after Pavlo Nakhimov and his fellow students, is singing the Ukrainian anthem. At the same time, the Russian occupiers are replacing the blue and yellow flag with the Russian tricolor. Immediately afterward, the young man moves to Odessa, where he continues his studies. Since 2019, he has served as a senior assistant to the commander of the search and rescue vessel “Donbas.”

Cadets of the Pavlo Nakhimov Naval Academy sing the Ukrainian anthem. Crimea, 2014.

“Dima and I are from the same town in the Volyn region. We met in 2018. I was a student at Ternopil Medical University, and he was a student at Odesa Academy. Somehow, the stars aligned, so we ended up in one place and one time,” Valentyna says with a smile about her husband. “He is the kindest person I know; the guys could turn to him with any question. Sometimes, even in the middle of the night, they could call him, ‘Vadymovych, we have a problem.’ And Vadymovych would get up and go to help the guys.”

Dmytro Klymovych, senior assistant to the commander of the SAR Donbas.

The Klymovych couple lived in Mariupol. Valentyna was in her ninth month of pregnancy when the full-scale invasion began. The woman recalls that shortly before the start of the war, Dmytro repeatedly tried to convince his wife to go to her parents in Volyn, but she kept refusing. “I told him that I would not go anywhere without him, that he would stay with me during childbirth, and that it was out of discussion.”

When Dmytro called her in the morning on February 24 and told her to get ready, she didn’t argue, even though she still didn’t realize how serious the situation was.

“I packed some baby clothes — just in case I go into labor on the way. I took the documents I had prepared for the maternity hospital and the cat. That’s how I left, leaving my husband and my house behind,” the woman recounts. “It was a long and hard drive. We were traveling through the Zhytomyr region when the bridge was blown up. We had managed to cross it before the explosion. I can’t even imagine what would have happened if we hadn’t.”

Though Valentyna stayed in touch with Dmytro for the first few days, her husband hardly told her anything about the situation in Mariupol. Valentyna didn’t ask either, as she just wanted to know that Dmytro and his comrades were alive and not giving up. Later, the connection in the city began to disappear, and Dmytro said he would write or call once in three days.

On March 9, Russia launched an airstrike on the maternity hospital in Mariupol. Valentyna worked at that hospital, so she called her husband to find at least some information about her colleagues. The next day, on March 10, the couple’s son Timofii was born.

Mariupol maternity hospital after Russian shelling.

“On March 12, Dmytro called me, and I told him he had become a father. There was no contact with him for the next three days. On March 15, a guy called me saying he was from Dmytro, that my husband was on a mission, and everything was fine with him. On the evening of March 17, my husband wrote to me himself asking about our son and what he was like because he couldn’t download any photos,” shares the sailor’s wife.

At that time, most of the sailors from the ship “Donbas” were under the command of the Azov Regiment. They gained access to Starlink connection, so there was minimal communication. It was the first time that Dmytro saw his son’s photos. “I sent him our son’s birth certificate, and we were happy together that the boy was already a week old,” Valentyna recounts. On March 21, she talked to Dmytro for the last time.

“He didn’t tell me much. They would carry some mattresses, arrange a place to sleep, or constantly change shelters because they were often shelled over. When he called the last time, he sounded so happy, telling me he was full and safe. The guys told me later that they had a good lunch that day – one tin of food for the five of them – but Dima didn’t eat it.”

On March 31, Valentyna received a call from an unknown person who introduced himself as a civilian and informed her that Dmytro was in captivity in Berdiansk penal colony No. 77. Later, the woman discovered that after the sailors started to run out of ammunition and food, they tried to escape from the occupied city. The sailors were taken out first, followed by the officers. However, Dmytro was stopped at a checkpoint because something on his phone aroused suspicion among the Russian military.

Berdiansk penal colony No. 77.

Since then, Dmytro’s detention place has been constantly changing. Several times, Valentyna received calls from the military personnel released from captivity, who informed her of her husband’s whereabouts. Currently, he is in Russia. Valentyna is deeply concerned about Dmytro’s health. She says that he suffered two concussions in Mariupol, and in captivity, he had problems with his legs. The released from captivity Ukrainian military personnel also informed Valentyna that Dmytro’s heart was stopping, but he received timely medical care. Dmytro also lost a lot of weight: before the captivity, he weighed more than 100 kilograms, and now he weighs about 60.

“The guys say he is holding on, supporting everyone, and not letting anyone feel down. Everyone assured him he would be home by his son’s first birthday, but it didn’t happen. It was a bit of a blow to him, as his son is one year old, and he still hasn’t seen him,” Valentyna explains.

In captivity, he lost almost half of his weight.

Serhii Zlenko was also one of those who sang the Ukrainian anthem on the parade ground of the Naval Academy in 2014. After that, he transferred to Odesa. During his studies, he served on the flagship of the Ukrainian Navy, the “Hetman Sahaidachnyi.” In 2019, he signed a contract and transferred to the search and rescue vessel “Donbas,” where he served as the commander of the electrical engineering division.

The connection with Serhii started to disappear on February 22 – the man explained that there was a lot of work on the ship. On February 24, at 6:30 a.m., Zlenko called his fiancée, who stayed in Odesa, and informed her that they were ordered to evacuate from the ship because the war had broken out.

Serhii Zlenko, the commander of the electrical engineering division of the SAR vessel “Donbas.”

“At first, I didn’t believe the war had actually started. But Serhii told me to take care of myself and promised to call when they found a new deployment location. He called the next evening and told me about all the locations they had been at,” Tina, the sailor’s fiancée, recalls in a conversation with MIHR.

Serhii would calm her down, reassuring her they were fine and everyone was safe and sound. At the same time, he told her that some of his comrades had received shrapnel wounds.

“I asked him if they had any food. He would send me photos of what they were eating and drinking. I even couldn’t tell if it was porridge or something else – it looked strange. He would also send me a photo of a cup, but again, I couldn’t tell if it was tea, coffee, or some compote. It seems like some locals would bring them food, as far as I understand,” the girl recounts.

The knight helmets that soldiers used for heating up.

Serhii would often ask about life in Odesa, and Tina would reply that everything was fine, trying not to worry him unnecessarily. On March 13, he called and told her they might retreat, but the girl didn’t understand what he meant because of the poor connection.

There was no contact with Serhii until March 19, and then, he called from an unknown number because his phone had died. He called several more times, explaining that they were heading closer to the city suburbs, looking for something to eat, and had made a plan. On March 21, an SMS came from an unknown number, saying, “I’m fine.” This was the last message from Serhii.

Zlenko and Klymovych tried to escape from the besieged Mariupol but were detained at a checkpoint.

“I would call him and text, ‘Call me back. Get in touch.’ I would also text that unknown number, but it was turned off. A few days later, the number from which I received the last message appeared online. I called and was told that they would contact me. That’s it, no one else got in touch,” Tina shares her story.

Sometime later, the woman received a call from an unknown man who informed her that he was a retired military officer who had been held in the same cell as Serhii in Berdiansk penal colony No. 77. Then she got information that Serhii had been transferred to Sevastopol, where the captives were severely beaten, and later taken to the territory of the Russian Federation.

Tina is concerned about her fiancé’s health. From the soldiers who were released from captivity and saw Serhii, she learned that he had significantly lost weight.

“He was captured weighing 115 kilograms, but since then, he had lost half of that weight. He has chronic illnesses and may already need some therapy. I’m frightened about it. There is a tendency for cancer in his family, so I’m very anxious that something may happen to him during this time.”

On August 2, 2022, Serhii’s parents received a letter from him. On December 31, a guy who was held in the same cell as Serhii was released from captivity, and since then, there has been no information about him.

“I already don’t know what to think. I’m grateful to people who provide at least some information when released. They say Serhii’s alive, which makes things easier for me. But on the other hand, I’m not sure about it. I haven’t seen or heard him; he hasn’t written or called – nothing. I only have to comfort myself with some illusions,” the sailor’s fiancée explains.

He still doesn’t know whether they got out of Mariupol.

Ohannes Arutiunian hails from Makiivka. When the Russian invasion began in 2014, the man moved to Mariupol with his family. He worked as a construction worker and owned a business, but the family lost everything because of the war. Unable to accept what was happening, he decided to go and fight in the war in 2017.

Ohannes Arutiunian, an instructor of the emergency rescue team on the SAR vessel “Donbas.”

“We have two sons. The kids were growing up, and he could be away from home for up to half a year. So I insisted that he transfer closer to home. That’s how my husband ended up on the ship “Donbas,” Oksana, the sailor’s wife, tells MIHR.

She knew almost nothing about her husband’s fate after February 24. She and her sons tried to get out of the besieged Mariupol. There was neither connection in the city nor gas or electricity. To get at least some information, they had to risk their lives by going up to the roof of a multi-story building under shelling.

“We got occasional SMSes; he was looking for us. Someone informed him that we were taken away, but we were not. There was his mom, me, and two sons. The last SMS was sent to his mother’s phone. He texted that everything was fine and asked where we were. We replied that we were still in the same place and address, but there was no response. There was no more connection, and we were afraid to go up to the ninth floor because the elevator shaft in the neighboring entrance was hit with a missile,” Oksana shares her experience.

Destroyed Mariupol.

The woman didn’t know until the last moment that the “Donbas” crew had disembarked at the port and that her husband and his comrades-in-arms were fighting in the city. The Ukrainian military often came to their yard, calming people down and bringing food, but they couldn’t provide much information.

“I had no contacts with his comrades; I didn’t know anything, and he didn’t tell me. When we were walking out of Mariupol, I had nothing at all. I didn’t bring anything with me; I even couldn’t imagine it would happen like that. And then it all burned down, and the house was gone. The only thing I managed to do was to take his passport,” the wife recalls.

Oksana and her family managed to reach the Ukraine-controlled territory on May 25. Only then did she manage to gather information about Ohannes. As it turned out, in mid-March, the man received a bullet wound to both legs in the 17th district of Mariupol. He was then taken to military hospital No. 555, relocated to the plant named after Illich after the airstrike.

Many wounded were taken to an underground hospital set up at the Metallurgical Plant named after Illich.

On April 12, 2022, everyone at the Illich Plant was taken captive, including Ohannes Arutiunian. Oksana knows that he spent some time in the Olenivka colony. In December 2022, a man released from captivity contacted and informed her that Ohannes had leg injuries, making it difficult for him to walk, and he was transferred to another place of detention. Later, Oksana received a phone call from the wife of another released captive, and she found out that her husband was in one of the detention centers in Russia. One of his legs has healed, but the other is still not okay.

The woman hopes the Red Cross will deliver a message to her husband and attend him in captivity, as Ohannes still does not know whether his family is alive.

“I don’t ask anything else from them anymore, just to tell him we are alive, to make it easier for him. Our younger son is only five years old, and my husband is worried. Because at that time, many people were killed – they were dying right before our eyes. I know at least something about him, but he knows nothing about us,” the wife of the captured sailor recounts.

Where is my dad?

Staff Sergeant Roman Andreichenko is a technician of the emergency rescue team on the SAR vessel “Donbas.” Born in Konotop in the Sumy region, he started his career in the Ukrainian Navy in Sevastopol on the frigate “Hetman Sahaidachnyi.” When Russia occupied Crimea in 2014, he stayed faithful to his oath, so he transferred to Odesa, where he met his future wife, Olena. He resigned from the service in 2017 but returned to it in 2021. His ex-comrades from the “Hetman Sahaidachnyi” suggested he join them on the ship “Donbas.” Olena moved to Konotop with their child, and Roman went to serve in Mariupol.

Roman Andreichenko, a staff sergeant and a technician of the emergency rescue team on the SAR vessel “Donbas.”

“He managed to come and visit us on New Year’s Eve. We had a conversation where he asked me, ‘What if there is a war? What if I come back without a leg?’ I couldn’t even imagine such a thing. He must have suspected something because when he came, he would watch various videos about the war and how the captives were held before. He didn’t explain anything to me; we just had a conversation. ‘If something happens, will you wait for me?’ he asked. ‘Of course, I will,’ I replied, ‘but nothing will happen.’ However, the war did start,” Olena recounts.

On February 24, at 5:30 a.m., Roman called his wife and told her that the war had started. Whenever possible, he called Olena but told her very little about what was happening in Mariupol, only reassuring her that he was fine. Then, the connection with him disappeared.

Since Roman served on the “Donbas” not for that long, Olena had no contact with his comrades. However, the sailors’ relatives started looking for each other to collectively search for the missing crew. That’s how Olena learned that on March 17, the positions where the guys were located got under heavy shelling. And on March 21, Roman called.

“It was around 9:30 a.m. He sounded frightened. I asked, ‘My God, are you alive? What is happening there?’ He replied, ‘Honey, there’s nothing left: we changed our clothes and are leaving the city,’” Olena recalls. “As we later found out, they had already reached Manhush; there were five of them. Roman explained their car had been hit directly, so they changed into civilian clothes. They only had phones in their hands, and what they found in the car, no documents.”

That was the last call from Roman; he never got in touch again. On March 26, a stranger called the sailor’s mother and informed her he had stayed with Roman in a filtration camp in Dokuchaievsk. Later, Olena found out that her husband was detained at a checkpoint, as he was the first to go, and the Russian military personnel did not like something in his phone, so they took him for filtration. The wife did not know where Roman was held afterward – there was little information.

Everyone detained at the exit from Mariupol was taken to filtration camps.

“Our side has confirmed the information about Roman, but Russia has not yet confirmed it. Once, I made a request to the DNR justice department. A month later, they replied that Roman had been captured by the ‘Ministry of Internal Affairs’ forces on March 21 and that since July, he had been detained in the temporarily occupied territory of the Donetsk region,” Olena recounts.

Later, she received several letters from her husband: he wrote that he had problems with his teeth, making it difficult for him to eat. He mentioned that he was struggling mentally but still managing to hold on. Over the past few months, there has been no new information about Roman Andreichenko.

“My husband has a brave heart and unbreakable spirit. We are eagerly awaiting his return. Our four-year-old son is especially looking forward to it – every day, he asks, “Where is my dad?”

I didn’t believe until the end that he had died.

Another sailor who served on the “Donbas” vessel is called Dmytro Prymolennyi. He hails from the Poltava region. In 2012, the man was drafted into the army. As he wanted to serve in the Navy, he was assigned to serve in Sevastopol. Later, he signed a contract and started his service on the ship “Donbas.” In 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, he remained loyal to his oath and transferred to Odesa.

Sergeant major of the engine team of an electromechanical combat unit.

“In the morning of February 24, Dima called his civilian wife and told her to pack her documents and leave Mariupol. She didn’t want to go without him, but Dmytro insisted. No one imagined that such terrible events would happen,” Maryna Hnidko, the sailor’s sister, explains. “He also called us, not often, but at least we had some connection, although he said almost nothing. He worried more about us, asking if the Russians had reached our place.”

Maryna asked her brother what was going on and where they were, and he told her they had abandoned the ship and were moving around the city. Dmytro called every 2 or 3 days but didn’t provide any details. On March 12, he called for the last time.

“It was around 5 p.m. I thought we had talked for a long time, but when I looked at my phone later, I realized we only talked for 30 seconds. Dmytro promised to call again but never did,” Maryna recounts.

No one has seen Dmytro since March 18. One of his comrades-in-arms contacted his family and informed them that there had been a heavy battle with many casualties, including members of the “Donbas” crew. Dmytro Prymolennyi was among the casualties.

“I didn’t believe it; I kept saying I wouldn’t believe it until I saw the body. Something told me that my brother was not dead. We monitored all possible public news sources to find at least some information. There was a photo of a burned body on Russian websites; it was lying face down and resembled Dima. But we still didn’t believe that it could be him.”

On April 12, when the entire garrison stationed at the Illich plant was captured, Dmytro’s relatives were informed that someone from the military had reported the capture and mentioned several names. The surname Prymolennyi was on that list.

As it turned out later, Dmytro was wounded and taken to the hospital at the Illich Plant, where he ended up in captivity. This was confirmed on April 24, 2022, when a photo of a notebook in which doctors kept records of the wounded at the Illich plant was published in a Russian public forum.

“The lists were kept by brigades. And here we see the ship “Donbas” followed by the surname, first name, patronymic, year of birth, and Dima’s diagnosis: shrapnel wounds to both lower limbs. That was the only information we had,” Maryna recalls.

The family hoped the man would be exchanged soon, as he was wounded. On the eve of May 9, rumors started spreading about the exchange, but Dmytro was not returned to Ukraine.

The first great exchange took place only on June 29, 2022. Then, 144 people returned to Ukraine. Two of them called Dmytro’s family and informed them they had stayed in the same colony with him and had seen that he was wounded but walking.

All those captured on April 12 at the Illich Plant were first held at a filtration center in the village of Sartana. Later, they were transferred to Olenivka.

“That was the first news confirming he was still alive. Dmytro initially ended up in Olenivka; he was seriously wounded. Luckily, our doctors, who had also been captured, pulled him out of that condition. They stayed with him all the time,” the sailor’s sister recollects.

Later, the man was transferred to the territory of the temporarily occupied Luhansk region. “I don’t know whether Dima has other injuries, but we were told he was the only one in his cell with all his limbs. And that despite such wounds, our prisoners of war are forced to work. In their room, they took turns cleaning up; however, Dima took over that duty because the other guys were on crutches,” Maryna shared her information.

While some were defending the port, others were fighting in the city.

The combat history of the “Donbas” vessel began on March 20, 2014, when the Russian military seized the ship during the occupation of Crimea. At that time, it was a command ship. However, on April 18 of the same year, the vessel returned under the Ukrainian flag and was transported to Odesa. In 2018, the command ship was converted into a search and rescue vessel under the authority of the military unit A0373, based in Berdiansk. As of February 24, 2022, it was stationed in the commercial port of Mariupol, conducting anti-submarine and sabotage defense.

The search and rescue vessel “Donbas.”

“We had no heavy weapons or anti-aircraft systems. We only had AK rifles, PMs, and a heavy machine gun. It was purely for our defense,” a member of the “Donbas” crew, whose name is not disclosed for security reasons, recalls.

As he accounts, the ship’s crew was alerted at 4:30 a.m. due to significant Russian warships in the Sea of Azov and Russian military planes approaching Mariupol. The commander of the “Donbas” decided to evacuate the crew to a secure location.

At that time, the port also housed military boats equipped with air defense systems, and later, a unit of the “Azov” detachment arrived. It was decided to mine the port area. A small group of the “Donbas” crew, led by two ship commanders, stayed in the port for mining operations; the teams of other boats and one of the “Azov” regiment units remained to defend the port.

Another soldier who served on one of the boats in the defense of the port explains, “Our mission was to prevent enemy troops from landing. A Russian warship used a civilian vessel to search for mines in the port. We had civilian dispatchers who guided that vessel safely, but the next day, we used two boats to mine even more of the port area. The Russians attempted to use their own small boats, Raptors, to clear the mines, but we allowed them to come closer, and the Azov Regiment struck and sank their vessel. This thwarted their attempts to attack the port.”

The port of Mariupol.

Another group of the “Donbas” crew went to the city, where they joined the A3057 military unit of the National Guard of Ukraine.

“We were subordinated to the National Guard, but as a separate unit called “Donbas.” We were engaged in defense of the control and observation checkpoint,” the military man recounts. “By the way, probably half of us had no bulletproof vests, and only about 30 percent had rifles. The National Guard equipped us and provided us with weapons. Since we were a ship’s crew and spent all our service time at sea, we didn’t quite understand how battles were fought on land. The guys from “Azov” understood that, so they assigned our unit to defend a less dangerous area where the command was located.”

The senior officer of the unit, chosen by the soldiers, contacted the command of the Ukrainian Navy, who would decide how to evacuate the sailors from Mariupol. However, everyone realized that they would not be evacuated. “We decided we would stand side by side and follow the orders of the sector commander,” the soldier explains.

The ring around the city was closing, and by mid-March, Mariupol was surrounded. As the soldier accounts, from March 1 to March 15, all the attempts of the Russian troops to enter the city failed.

“The Azov soldiers organized the defense so well that the Russians didn’t manage to break through for 15 days.”

However, the enemy troops eventually established a position in a building, leading to casualties among the Ukrainian units. “Initially, we defended the first buildings, but the Russians took them over, prompting our troops to retreat and suffer losses. The fighting continued along the entire perimeter of the city. In our sector, we lacked people for defense, so the commander assigned a group of 12 soldiers from our crew and “Azov” to perform the task. They went to clear the building, but not everyone returned from the mission.”

Heavy battles were going on in the city, so the crew of the “Donbas” began to be involved in combat missions. Russian troops were advancing, while Ukrainian troops were gradually retreating. There was no connection, and no one could learn what happened to those who had not returned from their mission. The wounded were taken to hospitals and transported to the Illich Plant or Azovstal afterward.

Many sailors from the “Donbas” and small boats are still in captivity. Most of them were seriously wounded during the defense of Mariupol.

This publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework «European Renaissance of Ukraine» project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation.