Testimony and trauma. Alma Taso Deljkovic on how trauma affects the judicial process and how to work with it in Ukraine

Psychologist Alma Taso Deljkovic is one of those who joined the creation of a victim support system in the courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina about 20 years ago. The war on the territory of the country with Serbia, Montenegro, and Croatia lasted from 1992 to 1995, but national courts are still hearing cases of war crimes committed at that time. Alma also advised establishing a similar system on national level in B&H as well worked with victims in Georgia when she was involved in the ICC Trust Fund. She says the process is almost the same everywhere: the system should help victims go through the court without additional harm. As a trainer, she is helping create the Coordination Center for Victims and Witnesses at the Prosecutor General’s Office. In an interview with MIHR, Alma explained how and why traumatic experience affects the quality of the trial and what to do about it.

Trauma, court and memory

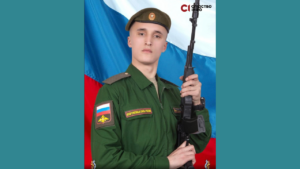

On November 7 2023, we met in Irpin court at a hearing in the case of Andriy Medvedev, a captured Russian soldier. He was accused of war crimes during the occupation of Kyiv region last spring. The hearing started almost three hours late. All this time, the victim, his defense lawyer, journalists, and free listeners waited together in a small hall and on the porch. What do you think about this situation?

— From the perspective of victim support, everything – from the entrance to the court to the hearing itself — should have looked different. Because what happened there was terribly wrong. First, the victim was called out loudly at the entrance, meaning everyone knew who this person was. You never know who is waiting before the entrance and whether someone there could threaten the victims. In addition, this method of calling is tough for them. There are many other ways to check whether the victim or witness has arrived, to allocate a separate room for them to wait where there are no journalists or other people who want to talk to them. In most cases, a person is very stressed before the hearing — not only because of what they will say but purely because they are in court.

Secondly, I don’t understand why witnesses or victims are summoned to procedural hearings. They do not need to listen to the indictment or discuss whether to accept material evidence. It is also vital that their testimony may change depending on what details they hear during such meetings. This is harmful for both the court and the prosecutor.

In this case, it was a waste of time — the person was just waiting, stressed, did not say anything, and heard something that could affect his testimony. I also did not see anyone talking to the victim after hearing about this situation — neither the prosecutor, the lawyers, nor the court staff. And this could happen again in a week.

What are legally described as war crimes can be considered potentially traumatic events from a psychological point of view. They can leave a mark on a person’s psyche and cognitive abilities. This is likely to have implications for the quality of testimony, which brings us back to the realm of the law. So, how does trauma affect memory?

— When a person with such experience testifies, it can re-traumatize them. You have to go back to these events and tell them. For a person with a trauma-related disorder, this can feel like something that is happening now, not in the past. It can provoke psychological or somatic reactions, and the story’s details can become triggers. It can also bring to the surface memories that the psyche has “frozen.” All of this can harm a person, so the judge, prosecutor, or defense attorney must understand the consequences. Witnesses or victims should testify as few times as possible. It is important to observe and support them during this time.

Sometimes, elements of the testimony are not connected. Traumatic memory is preserved in fragments because, at that time, it was easier for a person to cope with it in this way. Talking about it is like connecting the dots. But sometimes it is too difficult, so there are gaps. Some parts seem to disappear, and others, on the contrary, become more acute.

For example, I helped one of the witnesses who was repeatedly raped by several men in a prison camp during the war. She was six months pregnant, her son was sent to another village, and the younger one, 6-7 years old, was with her in the camp. Her husband was in another. Eventually, almost 20 years later, one of the men who raped her was detained and tried in Bosnia and Herzegovina. She agreed to testify against him.

I had several preparatory conversations with this woman. She had psychiatric problems and was taking medication, so I talked to her psychiatrist. And also with her daughter, with whom she was pregnant at the time — she was now about 25 years old and taking care of her mother.

The woman came to the court confused and crying but eager to testify. She attached importance to very small details, such as wearing white clothes and a necklace, which meant something. We went into the courtroom together, and the judge explained who else was at the trial — she also mentioned the accused’s name. But the woman did not hear it.

During her testimony, she cried a lot, had emotional ups and downs, and had various emotional reactions with somatic manifestations. It was felt that sometimes she talked about the event as if it was happening now. These are things typical of the process of retraumatization. When the woman finished, I asked her if she was okay and if she wanted to take a break. She said she was ready to continue.

Next came the defense’s questions. The lawyer said he had no clarifications. Then, the judge asked if the accused had any clarifications. He only said: “No”. And that was more than enough. The woman turned to me and asked in confusion: “Who is it?” I explained that it was the accused, and she started to speak: “But his voice, his voice…” She was completely broken, started crying and trembling, repeatedly saying that she had to leave.

I had explained to the judge what could happen beforehand, and we agreed that I would say when a break was needed. The judge gave a break for 15 minutes. We had barely left the courtroom when the woman fainted. All of her body systems were so overloaded just because of this one trigger that she completely lost her temper. She could not continue the hearing. She was given medical care, and then we, together with the police (because she was protected as a witness), took her home and handed her over to her daughter.

The case you describe concerns illustrative, vivid signs of PTSD. But if we are talking about less radical cases of trauma or when a person does not cry or name their condition, how can they be recognized? Through somatic manifestations, for example.

— They depend highly on the human ability to process and overcome trauma.

There are three groups of reactions: “fight,” “run,” and “freeze.” Accordingly, there will be three types of responses. Much depends on how the person first reacted. That is, someone can be aggressive, and this aggression towards themselves or others is, in most cases, associated with the guilt of the survivors. Trauma manifests itself through blocking emotions and reactions, dissociation, and denial. Tears, on the other hand, are more likely to be associated with healing.

Often, during testimonies, you can see how a person momentarily blocks and forgets where they are and what they have to say. We call these memory lapses, but this does not mean that the person has forgotten some episodes — these memories are there but blocked so that the person can survive. A great explanation is that a traumatic memory is put into a box, hidden in a closet, and the door is locked. To talk about what happened, you have to open all the locks. This is not the case with ordinary memories. The primary mission of the body is to survive and not lose itself, and the brain is looking for a strategy for this. But no two people can cope in the same way. That’s why we need to develop an individual approach.

The cases being heard in the courts in northern Ukraine relate to events that happened almost two years ago. It seems that lengthy proceedings may become a trend for war-related cases. How does time affect memories of such events?

— This is a common issue for Bosnia and Herzegovina because we are still working with cases of war crimes from 20-30 years ago. Sometimes trauma is remembered very vividly as if the memory is happening now, as if it were a movie. Some people remember everything — time, weather, smells, the color of trees and buildings. And some people remember nothing. Of course, after many years, you can forget something. But I think that in most cases, people with such a specific experience remember most things. They cannot forget it.

During this time, a person can also “heal” — in the context of traumatic memories, this means that they integrate into normal memory. Can this affect their clarity and become a problem for the court?

— Yes, the main task of healing is to integrate that experience into ordinary life and learn to cope with it. This is acceptance, not forgetting. I don’t think the details can be lost. I have seen so many victims who went through so many terrible things, who lived and went through healing with the help of professionals or on their own. But it is impossible to forget about it.

Now, we are talking about cases of PTSD, but most people do not develop this disorder after potentially traumatic events. What should judges, lawyers and prosecutors be aware of in other, less drastic cases?

— They still need to have trauma training to understand everything about traumatic experiences and how they can work with them from their perspective. But they also need to understand their condition — maybe some of them also have traumatic experiences and need to learn how to deal with them. Because, perhaps, tomorrow in court, someone’s testimony will affect them personally. The judge, lawyer, and prosecutor must be objective, keep the process under control, and not harm themselves.

Ukrainian support system

You are now in Ukraine to conduct similar training for the Prosecutor General’s Office, which has created a new department to support victims of war. Please tell us more about this work.

— It is a great honor for me to help establish the Coordination Center in Ukraine. This team has a lot of work ahead of them. They have to learn many things to work with their own experience, as well as with witnesses and victims.

This is a very mixed group: lawyers, psychologists, social workers. I was very honest with them. I wanted to show them what this work is like. They had to be prepared for what they would hear and see, and they had to know how to help. During the two days of intensive training, I saw a great understanding of why this topic is important, but they had just started their work.

What needs to be done to make this system work in Ukraine?

— First of all, they need to start working. Start contacting witnesses and victims as quickly as possible, immediately. This is the only way to apply the things they have learned. And during the process, they will understand what to do with it.

But from the point of view of someone who has been in the process for so long, I know that they have to support people on different levels. Not all witnesses and victims have the same need for support — someone needs psychological help, someone needs information, someone needs psychoeducation. The process must be built on different levels, including the administrative level. For the system to work, the department must have excellent communication with prosecutors and judges, explaining their role and the importance of support at all levels: the first contact with the police, the first testimony, the first hearings, and so on. It is vital to work so that support does not interfere with testimony — this is the biggest concern of prosecutors and judges.

Their task is only to make sure that giving evidence does not harm the person. First, explaining in detail what the process will look like is necessary because most people need to learn how the judicial system works. Secondly, it is necessary to conduct psychoeducation — to explain what can happen to the body when talking about traumatic experiences, what emotions can come to the surface, and how retraumatization works. Thirdly, describing how to deal with this during and after the trial is important because it is very important not to leave the witness or victim alone when they testify. Obviously, the experience will not disappear by itself when the person leaves the court or the prosecutor’s office.

And the last thing to do is to give them contacts of people in their communities who can help if needed. For example, it could be social services from government or non-governmental organizations. This should be built into the program.

Prosecutors and judges need to understand what is happening to a witness or victim at a particular moment. For example, when a person testifies, they experience complex emotions, and judges should understand before and during the hearing what to expect when to pause, how to explain to other participants why questions should be asked carefully, and what wording is inappropriate.

In other words, everything needs to be changed to give witnesses and victims the feeling that the system has not simply used them.

— Yes, this is the biggest challenge for such a support system worldwide. The court and the prosecutor’s office are not social structures. They are part of the justice system. So, they have to follow the institutions’ rules, but at the same time, they have a moral and ethical responsibility to care for witnesses and victims. A person will stop contacting the court when they finish testifying or come to the verdict. And the work of the support system in the prosecutors offices and at the courts ends there. But we can create referral mechanisms to which we will refer this person in the future, if necessary so that their own community can help them. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, we realized this as soon as we started working with war crimes 20 years ago. We could not say to people: “Well, our work is done, that’s it”. That would be wrong. That’s why we created a witness support network across the country comprising various NGOs and government institutions. I think this approach can work in Ukraine because so many NGOs and government institutions can take on this work. But it needs to be organized and publicized.

Expectations and justice

You talk about prosecutors and judges, but defense lawyers are also part of the process. What should their work look like? Are there strategies to ensure that they do not retraumatize witnesses and victims?

— The Witness Support Office, which is part of the court, is neutral. Therefore, it can work with the defense, its lawyers, and witnesses. Defense lawyers are also people.

They need to know how to deal with the stories they hear. And it is the judge’s job to direct their questions. That is, the judge can allow or prohibit clarification, depending on the condition of the witness or victim. A person from the support system can tell the judge about this condition.

In Bosnian courts, the judge can say at the beginning of the hearing that there is a statement from the Witness Support Office about the witnesses’ psychophysical condition, so all parties need to be careful. Judges should not allow questions that could be harmful.

The last thing I wanted to talk to you about is the expectations of victims. How can trials, especially in absentia, affect their sense of justice, and how can this affect their connections within society?

— Working with expectations is always difficult, both on an individual level and on a societal level. I have seen many trials and verdicts, but I have not seen a single verdict that everyone is happy with.

People need to know that they have to fight and be strong. Eventually, justice will come. It is impossible to meet everyone’s expectations, but you have to keep motivating yourself to work. The role of witnesses and victims is vital — they must help the court and the prosecutor find the best way to justice.

Alma Taso Deljkovic (in the chair on the right) during a training session at the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine

Is it possible that people might feel more emotionally traumatized at the end of the investigation and trial than they did before because they will see that the process does not meet their expectations?

— Probably so. But even in this depressed and exhausted state, we must continue to fight, to testify, to be proactive. The verdict depends on it.

The court works with evidence and testimony, and the final verdict will be based on that. For example, many complex cases in Bosnia and Herzegovina were investigated thanks to the activity and persistence of victims’ associations.

If expectations are still unmet, could this struggle be a healing process rather than justice?

— Yes, perhaps.