The Russian Headquarters in a Kindergarten and a Torture Chamber in a Village Club: Details of the Occupation of Novyi Bykiv

—Two jeeps arrived from Bobrovytsia and fired from a machine gun. They could have driven quietly through our village but were slightly scared at the bend. So they set up their almshouse here. We have a lot here: a kindergarten, shops, cars, gas stations, a national road, — Nataliia Yermak, director of a kindergarten in Novyi Bykiv, recounts. —The Russians used to call this village in the Chernihiv region a town.

—They come in and ask, “What town is it?” — Vasyl Tyrpak, Nataliia’s husband, recalls.

—This is a village, what town?! — I tell them.

—No, this is a town! — they reply. They have no idea what a village looks like.

The Russians entered Novyi Bykiv at the very beginning of the full-scale war. On the first day, they tortured and killed several young men from a nearby village; their bodies were taken by their families only after the liberation. The Russians set up checkpoints, dug trenches, and patrolled the streets in APCs. Men were forbidden to go outside, with warnings that they would be shot without warning. The enemy established their headquarters in the local kindergarten and turned the boiler room of the village club into a torture chamber for prisoners of war and civilians.

Vasyl Tyrpak against the backdrop of destroyed buildings in Novyi Bykiv. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

—When they arrived, they immediately damaged the gas system and the tower near the school, which supplies water to half the local population. The well also dried up, so there was no water anywhere, — Nataliia Yermak recalls.

In addition to the gas, the village lost electricity and communication: to prevent the Russians from advancing further, Ukrainian troops blew up the dam and damaged the communications. The locals believe there were about 1,500 occupiers in the village. When asked where they had come from, they responded that they were forbidden to tell.

Nataliia and Vasyl continued to take care of the livestock.

— We wouldn’t go through the checkpoint, but between the bushes so no one would see us. But once, while we were walking, they started shooting at us, — Nataliia recollects. — I asked them then, from what distance can a person be killed?

—About 800 meters, at most a kilometer and a half, — they replied. —So I ordered Vasyl to dodge and never walk straight.

Over time, the occupiers reconnoitered the roads and began bringing more and more military equipment into the village. They placed it between houses and civilian buildings. Locals were forced to dig graves. Vasyl and Nataliia also had to do this:

— We were all walking down the street, about 15 people. And there were 15 of them, with automatic rifles. One soldier ordered, “Come on, you’ll help us work.” That’s how my husband and I were forced to dig a grave.

Nataliia Yermak, director of the kindergarten in Novyi Bykiv. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

Gas House

The Russians set up one of their headquarters in a two-story building behind the cemetery. Vasyl Tyrpak would frequently pass it by on his way to the cellar for food. To avoid being bothered, he would give the occupiers apples or bread. Once, he even came under fire but escaped unharmed.

On March 19, Vasyl Tyrpak and his neighbor Maksym Didyk went to milk the cow. Previously, Vasyl used to do it with his wife, and they usually finished in about an hour to an hour and a half. However, that day, the men were late.

— Freeze! — They heard the order, and ten Russian soldiers appeared. Vasyl and Maksym were detained and accused of adjusting artillery fire.

—You’ve got to be kidding! I have a push-button phone! What coordinates could I possibly be sending?! — Tyrpak protested. But it was all in vain.

At first, the men were separated. Maksym Didyk was taken to a local separatist who was helping the Russians. In captivity, Maksym did household chores, was tortured, and taken to be executed, but they spared him. The young man was released 12 days later. Vasyl was thrown into a pit measuring three by one and a half meters. Besides him, 7 or 8 people were held there, constantly changing. After a while, Tyrpak was put in a car and driven around the village for about a day until he was brought to the “gas house.” That’s what the locals call the club’s boiler room. Prisoners from neighboring villages were also taken there, including Viktoriia

Andrusha, a math teacher from the Brovary Lyceum, who was then held in Russian captivity for six months.

People in the gas house constantly changed; at the same time as Vasyl, about 20 prisoners stayed there.

The Russians held Vasyl Tyrpak and other Ukrainians in the cramped basement of the boiler room. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

—I remember when four guys, around 30 years old, were brought from Mala Divytsia. The Russians would beat them so heavily and torture them so horribly! It was terrifying. The screams were unbearable. I already said it would have been better if they had been shot, — Vasyl Tyrpak recalls.

Every day, the occupiers gave the detainees a military ration for two people and a bottle of water. Sometimes, they offered a newspaper and tobacco so the prisoners could roll a cigarette. However, usually, a group of three or four Russian soldiers would come to the prisoners, beat them, and then leave. One of the occupiers said he was a musician. It’s worth noting that this is what Wagner Group members call themselves. However, the victims are unsure whether this was the case.

—They kept asking me if I was giving coordinates of where they were stationed. So I explained to them in Ukrainian and Russian that I couldn’t pass over anything because I had a push-button phone. What could I possibly pass over, and who to?! — Vasyl recounts.

The boiler room, in the basement of which the Russians held Ukrainians in Novyi Bykiv. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

As soon as Vasyl starts recalling those events, he begins to cry. They would beat him with the butt of an automatic rifle, with their hands and feet, and strip him. Russian soldiers broke his arms and legs. They also knocked out his teeth, and after the torture, he began to stutter even more. One time, they tortured him so severely that they dislocated his hip joint. Later, the doctor would say that only three centimeters of living tissue remained there. Another day, and it would have all become necrotic.

The Kindergarten

The “gas house” was not the only headquarters the Russians set up in Novyi Bykiv. Another was established in the “Yablunka” kindergarten, which was managed by Vasyl’s wife, Nataliia Yermak. Before the full-scale invasion, it was the largest kindergarten in the district. It had undergone a renovation, featured heated floors, and hosted over a hundred children. It was a hub for seminars and even welcomed foreign delegations.

The kindergarten director, Nataliia Yermak, shows MIHR documenters the aftermath of the Russian occupation in Novyi Bykiv. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

— One day, I was walking and saw a Russian soldier carrying water, a very young guy — Nataliia recalls. — So I called him, “Hey, wait, where are you coming from?”

— I got water from over there. Come on, I’ll show you, — the young man replied. As it turned out, he was coming from a neighbor’s place near our summer cottage. I didn’t even know there was a gate there. I looked at him and said, “You are so handsome! What’s your name?”

— Vitia.

— Does your mom know where you are?

— My [commanders] told us we went on a 15-day assignment.

— Oh, my dear, I wish your mom would see you again.

Thank you.

— Where are you taking the water? — I ask him. — That’s my kindergarten. Or are you going to the two-story building?

— Do you want to see it? — He asks.

— Yes, I have so many flowers there. And an aquarium.

— Well, I watered the flowers on the second floor, but the fish died. Do you want to go there? — He asks. Then he looked at me and said, “Actually, you’d better not.”

After the village was liberated, the kindergarten was unrecognizable: shattered windows, a broken roof, damaged walls, collapsed ceilings, and bullet holes. This building was a strategic position for the occupiers not only because it provided cover for their military equipment but also because it had a shelter. Additionally, from the second floor, the occupiers conducted surveillance, and the snipers were stationed there.

The destroyed kindergarten in Novyi Bykiv, where the Russians set up their headquarters. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

In the same building, the Russians stored looted items: household appliances, pillows, toys, and food.

— But they were a bit dumb because they heated electric kettles on the gas stove. After they left, there was so much filth here that the girls were vomiting. Piles of condoms. They must have had some celebration. There were girls here—whether they brought them or they were theirs, who knows, — Nataliia Yermak recounts.

Freedom

After ten days in captivity, Nataliia’s husband was released. Before that, Vasyl Tyrpak had his eyes tied, a bag placed over his head, and was taken to a checkpoint near Pisky, where his son lives:

— A humane Russian soldier showed up. He saw that my leg was broken. He asked, “Grandpa, why are you sitting here?” I told him that I had been released but had no one to take me away. He replied, “Wait 15 minutes.” And when we arrived at the checkpoint, he ordered them not to touch me.

From there, Vasyl Tyrpak walked toward the Ukrainian-controlled territory. However, since his leg was broken, he had to move with the help of a chair:

—When you’re walking, you place it in front of you—then you slowly move forward. But once, I fell over. It was hard to get back up. I walked for three hours.

The consequences of the Russian military’s presence in the kindergarten of Novyi Bykiv village. Photo by Viktor Kovalchuk

Eventually, Vasyl made it to the home of an acquaintance, where he hoped to spend the night. However, she didn’t let him inside, thinking he was drunk. As a result, Vasyl spent the night in the summer kitchen. The hostess gave him water and a new chair to replace the broken one. During the night, he became very cold, and his fever developed in addition to his fractures. In the morning, he set off again but kept falling until he broke the chair for the second time and could no longer get up. Strangers saved the former prisoner. They brought him water and went to Vasyl’s son to inform him about his father. Until then, the family had no idea where he was or what had happened to him.

First, he ended up in Zhorivka, where doctors put a cast on his leg. A week later, an ambulance and volunteers came for him and transported him to Kyiv to the Trauma Institute, where he had a prosthetic implanted and continued his treatment.

—You shouldn’t lose heart! I keep telling myself I can still live, — Vasyl Tyrpak encourages.

De-occupation

Novyi Bykiv was liberated on March 31, 2022. The day before, the Ministry of Defense reported, that the Russians were using local children as human shields: taking them hostage and putting them in trucks to protect military convoys from shelling and ensure the locals would not give the Ukrainian military the coordinates of the enemy’s movements.

On April 2, the Ukrainian Armed Forces fully liberated the Chernihiv region. The same day, Nataliia Yermak and the SSU officers entered her kindergarten. She found broken cabinets, piles of stolen items, and Russian military documents, including logbooks and reports.

—There was so much here; it was terrifying. They brought everything from the entire village: bunk beds, mattresses, bedding. They lay there like kings. The floor was covered with a vapor barrier that they put on roofs now. They walked like they were walking on cotton. All the walls were draped with carpets. All the TVs from the village were here, too. Even mine. I found my blanket here and took it home, — Nataliya Yermak recounts.

On the grounds of the kindergarten, the occupiers also left shell casings, chevrons, and a logbook where they recorded who went where and when. What the locals found, they either handed over to the authorities or burned.

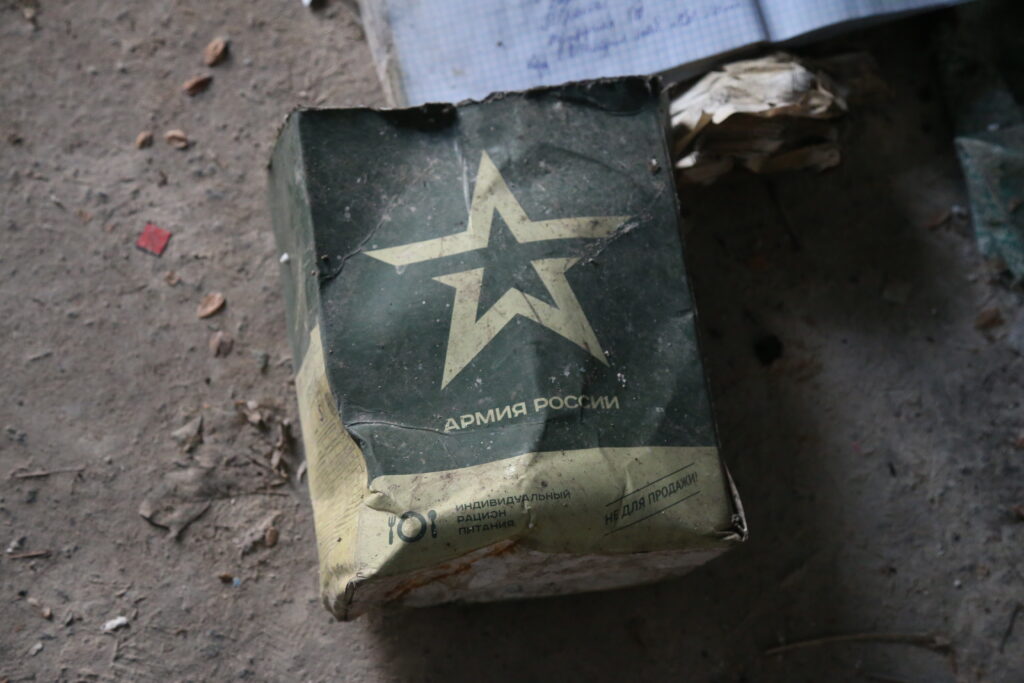

The packaging from a Russian military ration left by the occupiers in Novyi Bykiv. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

The village is still recovering from the occupation: buildings are destroyed, dozens of civilians were taken prisoner, a woman was run over by a Russian armored vehicle, and there were those tortured and killed — there is no one in the village who has not suffered from the actions of the occupiers.

— Even if not physically, everyone has been affected morally and mentally. And God forbid, it should never return, — Nataliia Yermak notes.

Yana Ilkiv, journalist MIHR

MIHR documenters Kateryna Ohiievska and Lidiia Tarash participated in the preparation of this material.