The Unwanted: how occupiers torture Ukrainian activists and then deport some from Melitopol

Without electricity, water, or food: they kept pro-Ukrainian activists in garages, containers, and pre-trial detention centers for over a month.

On August 22, the Russian military detained 27-year-old local resident Inna and her boyfriend, 29-year-old Oleksandr (names changed for security reasons) in the city of Melitopol, the Zaporizhzhia region. The couple was arrested for putting up patriotic flyers and ribbons for the Ukrainian Flag Day the day before.

Photo from Facebook

Saying, “now this is your home”, they closed one in an industrial iron container

“We began patriotic and educational activities after one part of the Zaporizhzhia region had been occupied,” Inna tells MIHR. “When they detained us, we did have Ukrainian symbols on our backpacks. Two people wearing masks and carrying assault rifles, dressed in civilian clothes and looking like locals or the so-called LDPR representatives got out of the car that used to belong to the Ukrainian police. They scolded my boyfriend, put handcuffs on him and threw him to the car trunk saying, “A bitch should ride in the trunk.” They allowed me to sit in the salon of the car. We were taken to a building on Chernyshevskyi Street.”

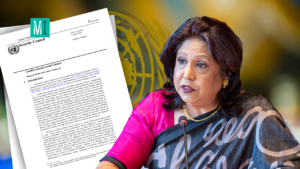

Photo: Ukrinform.ua

An unfamiliar blondie searched Inna and took her to the yard; there was an iron container (on the territory of one of the administrative buildings on Chernyshevskyi Street) similar to those loaded in seaports.

Photo: “Цензор.нет”

“The blonde woman said, ‘Now this is your home.’ She stuffed me in a container. It was two meters long, two meters wide and the same height. There were two wooden benches, similar to park ones but with large gaps between the steps. I slept on them. It was unbearably cold at night, hot as if in a sauna during the day. Twice a day I was taken to the toilet,” says the female activist.

They cut a 25 cm high window in the container on the fourth day

They did not feed the woman for the first three days. Then they started giving her cold food three times a day. There was neither light nor fresh air in the container. They cut a 25 cm high window on her fourth day there.

On her ninth day in the container, Inna was transferred to the building of the pre-trial detention center, located next to Center for Primary Health Care No. 1 – the “green” polyclinic (Melitopol city, 7 Ivan Alekseev St.), as locals call it.

The woman was kept in one of eleven cells there. No one visited her, she was fed mainly with Russian dry rations. On September 22, the “investigator” summoned Inna to talk to Russian journalists, who asked her about the activity related to the resistance movement.

“On October 4, they pulled a bag over my head and put me in a car,” the female resident of Melitopol recalls. “When the car stopped and the bag was removed, I heard from behind, ‘let’s just fire a bullet in the forehead, and be done with it.’ They put me next to a moat, pointed a camera at me, and read me accusations that I was committing extremist acts and a bad influence on the civilian population, so they deport me. They ordered me to go towards Vasylivka through the gray zone.”

The russian military “deports” a resident of the village of Uspenivka, Zaporizhzhia region

“Air was coming through tiny cracks between the bricks”

While Inna was in custody, her boyfriend Oleksandr changed three places of detention.

Oleksandr spent the first night in a large garage on the territory of one of the administrative buildings on Chernyshevskyi Street. 20 more men held there beside him.

“The detainees slept on bunks made of plywood,” says the man. “Some had mattresses. Some were lying on the concrete floor or squatting in a corner, some men were sleeping on bunks in pairs. There were no windows, but from above one could see tiny cracks between the bricks air was coming through. We were receiving no food. Some of the men were passed food by their relatives, and they shared it with other prisoners. We were taken to the toilet and shower once a day in the morning.”

The following morning, Oleksandr was taken to another garage on the territory of the car park, under the bridge, on the way to Novyi Melitopol. The garage to which the man was thrown was small. There were four other detainees held. Instead of a toilet, there were flasks and a bucket. They slept on rags spread on plywood doors. Food was given once a day. A small lantern hung under the ceiling and was kept on 24 hours a day, there were no windows.

“All four who were detained with me had been put there because of their pro-Ukrainian position,” says Oleksandr. “On the first day, four men of oriental appearance took me outside, put a bucket on my head, and started beating me. They also beat the bucket that was on my head. This hell lasted ten to fifteen minutes. They said, ‘You will die here, you bastard.’ Then they threw me back to the garage. In the evening, they beat me again. And the following day at lunch, they brought food and started beating everyone right in the garage. The detainees stood near the wall, the military came up, beat us in the ribs with a baseball bat, smashed that one over one of us, they beat us with rebar, iron bars, machine gun butts, and fists. Life in the garage was like a groundhog day – beating, taking a break, and beating again. I was beaten for the entire five days they kept me there.”

“One was pulling the switch – turning on and off the current, and the other one was sitting above me and yelling, ‘Who are y’all here, all Banderites?!”

On the fifth day, they took Oleksandr to the pre-trial detention center of Melitopol.

The man was held there until October 18.

“There was a non-working video surveillance camera in our cell. They fed prisoners with Russian dry rations and gave them no hot food. At the first interrogation, two people in balaclavas and with a Russian accent put clamps on my fingers and ordered me to give out the names of the ATO and SSU guys, and policemen I knew. They electrocuted me for 15 minutes. One of them was pulling the switch – turning on and off the current, and the other one was sitting above me and yelling, ‘Why the hell are so pro-Ukrainian here! Who are y’all here, all Banderites?!’ Those Russians said that the prisoners were Nazis and that they should be shot. After this interrogation, they did not touch me until October.”

“I had broken ribs and could not stand up. On October 15, I was taken out with a bag on my head to the doctor, who gave me some ointment and wrapped my ribs with an elastic bandage,” says the activist. “Among the detainees, there were three boys from other cells, who cut their veins at different times. I think they did it because of torture and psychological pressure. Those boys were taken to the hospital and then released.”

Oleksandr learned that his acquaintance, a local pro-Ukrainian activist, had been sitting in one of the cells for six months. Through a crack in the wall, he explained that there were also members of the ATO among the prisoners.

On October 18, they put a bag on Oleksandr’d head and took him to Vasylivka, the Zaporizhzhia region. There they read the resolution, which declared him an unwanted person in Melitopol. After that, the man reached Zaporizhzhia on foot.