Without Lawyers and Witnesses: How Russia Ignores the Rights of Imprisoned Ukrainians to a Fair Trial and What This Means for the Aggressor Country

At the beginning of the conversation, Maksym Tymoсhko, Officer of the International Law Department of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, , suggests going back 80 years to remember the Justice Trial—the trial of lawyers (also known as the “Judges’ Trial”) during the Nuremberg Trials in 1947.

This case concerned judges, prosecutors, and officials from the Ministry of Justice of the Third Reich. While the former were tried for their participation in unfair trials, Nazi Ministry of Justice officials faced the court for organizing a distorted justice system that used judicial power as a tool of enslavement, torture, and extermination. During this trial, the famous phrase about the accused was proclaimed: “Beneath the robe of the lawyer was hidden the knuckle-duster of the killer.”

“In essence, the Justice Trial is one of the first cases where the deprivation of guarantees for a fair trial was considered an international crime. Unfortunately, history repeats itself. Despite the many years that have passed since then, we recall this case in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, speaking about the responsibility of individual judges and prosecutors, as well as those officials of the aggressor state who have formed a repressive judicial system in the occupied territories,” Tymoсhko emphasizes.

Leave Everything as It Was Before the War

What, in your opinion, are the key criteria for a fair trial?

— Today’s understanding of a fair trial is rooted in the categories of the global legal order established after World War II. In 1945, the United Nations was created and the UN Charter was adopted as a foundation that formed legal relations both within and outside of states. In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The following year, the Geneva Conventions were established. Then, in 1950, the Council of Europe adopted the European Convention on Human Rights, which led to the establishment of the European Court of Human Rights. A little later, in 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was adopted within the UN system.

In each of these fundamental international treaties, the right to a fair trial is addressed. Therefore, when we talk about the criteria, we must rely on these documents.

The criteria for fair justice in the modern world are defined by the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Conventions, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The guarantees of a fair trial can be divided into two main types:

First – institutional guarantees. This means that the court must be properly formed and organized. It must be impartial, independent, and established by law. It must not depend on other branches of power, particularly the executive branch (as was the case in the mentioned Justice Trial).

Second – procedural guarantees: here we talk about the adversarial nature of the trial, the equality of parties, the right to a defender, the presumption of innocence, the right to be informed of the charges, the ability to question prosecution witnesses, the public nature of the trial, etc. These are tools that a person can use to challenge the accusations made against them.

The main idea of these guarantees is to provide an individual with levers against state arbitrariness.

Why do the judicial processes in the Russian Federation and in the territories of Ukraine occupied by it against Ukrainian citizens not fall under the category of fair trials?

— Because the entire judicial system is fundamentally flawed and has turned into a repressive mechanism against the enemies of the occupying power. But let’s try to understand this step by step.

It may be controversial, but from the perspective of international law, courts in occupied territories are not inherently illegal. Moreover, international law obliges the occupying power to ensure fair justice in the territories it controls.

The 1949 Geneva Convention on the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War devotes considerable attention to the establishment of law and order and the judicial system in occupied territory. At its core is the principle of status quo ante bellum, meaning “leave everything as it was before the war.”

In practice, this means that Russia should have retained the criminal legislation and judicial system of Ukraine in the occupied territories. However, Russia deliberately ignores the laws and customs of war and does not recognize its obligations as an occupying state. Instead, it annexed the occupied territories, which further exacerbates its responsibility.

Maksym Tymoсhko, Officer of the International Law Department of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

There are justified doubts regarding the legality of the courts established by Russia and the ability of this system to be independent and impartial. For instance, the formation of “courts” in the territories of the so-called DPR and LPR since 2014 was carried out by the “executive power” of these quasi-republics. What kind of independence of these “courts” can we then talk about? And how can one perceive the total refusal of Russian courts to apply international humanitarian law in cases concerning prisoners and civilians?

Many of those arrested do not even know what they are accused of. There are numerous cases where prisoners only hear the names of some articles but have no access to their case files. How can one prepare a defense in such conditions?

Zone of Lawlessness

In the occupied territories of Ukraine, Russia detains people without adhering to proper legal procedures. How would you characterize such actions?

— The occupied territories are a zone of lawlessness. All detentions usually occur without the intervention of judicial authorities. This indicates a certain tactic by Russia. When it needs to legalize something and use the court as a tool for this, it immediately involves it. However, when it wants to literally destroy someone, no court is needed.

The imprisonment of a person without cause is, by definition, a war crime. Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) mentions both the deprivation of a person’s right to a fair trial and the deprivation of a protected person’s liberty.

But military personnel, for example, can be deprived of their liberty.

— Yes, and for this, a court is not necessarily required. However, prisoners of war cannot be held in general places of detention; they must be placed in official internment camps. What do the Russians do? They treat Ukrainian military personnel as criminals and keep them in prisons.

At the same time, an occupier cannot just detain a civilian. There must be legal grounds, legal procedures must take place, and it must be documented. When this is not the case, it is a clear example of unlawful deprivation of liberty.

Testimonies from MIHR (Media Initiative for Human Rights) reveal that the civilian population in the occupied territories of Ukraine is detained, among others, by FSB representatives

If we delve into these cases, we see massive violations of procedural guarantees concerning lawyers and the equality of the process. Violations occur, for example, when the prosecution presents evidence to the court, but the defendant is restricted in this right. Or when the court “turns a blind eye” to important arguments that refute the prosecution’s claims.

Let’s also recall the presumption of innocence. Those videos where Ukrainian military personnel are forced to confess to some “crimes” even before the trial are shot by the enemy with one goal — to create the impression that they have caught a “criminal.” However, this violates the presumption of innocence, as only a competent court is authorized to establish guilt.

How does the integration of the quasi-legal systems of the so-called “LNR” and “DNR” into the Russian legal field affect the judicial processes against Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages?

— Essentially, nothing has changed. The situation has not improved for either civilians or prisoners. The main difference is that the “judges” of the so-called “DNR” and “LNR” have begun to issue rulings in the name of the Russian Federation instead of their quasi-republics. What has Russia actually done? It has extended its legislation to these territories, incorporating them into its Constitution.

What does this change for the prisoners themselves?

— For the person, perhaps nothing changes. But under international humanitarian law, such judicial processes should not be conducted outside the occupied territories. Such forced displacement can be considered a war crime.

Russian authorities implement a policy of colonization: they relocate their own citizens to the occupied territories and vice versa — resettle Ukrainians outside these regions. It’s about population replacement.

Maksym Tymoсhko states that the illegal detention and sentencing of civilians in the occupied territories of Ukraine is part of the colonization policy that Russia is implementing there. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk.

They also use the courts to implement this colonization policy: they take a person from the occupied territories and imprison them for, say, ten years somewhere in Russia.

You mentioned the right to a lawyer, which is also one of the criteria for a fair trial. However, Russia mostly neglects this right: Ukrainian citizens either do not have defenders, or they are purely formal, or there is no translation provided in court. What are the consequences of this for a fair trial and the accused individuals?

— We can usually assess the fairness of a judicial process only upon its completion, although there are exceptions to this rule. For instance, when a person is held in custody for years, as often happens in the occupied territories, without the right to judicial review of their detention and in violation of reasonable time limits for trial, we don’t need to wait for a verdict to state that their right to a fair trial has been violated.

The absence of a lawyer can, of course, significantly affect the fairness of the entire process. A detained citizen must have the right to choose a defender whom they trust and who will maintain attorney-client confidentiality. If the lawyer is appointed by the state, takes a passive role in the court process, and performs only a nominal function, this is certainly not enough to protect the individual.

Such lawyers often turn into prosecutors themselves.

— Yes, I recall cases when “lawyers” working in the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions acted as “second prosecutors.” Their job sometimes was to persuade the detainee to plead guilty. Generally, in cases related to the war, lawyers often serve as “negotiators” — conveying information to the detainee’s relatives and often being the only connection between the detainee and the outside world. This allows relatives to receive information about their physical and psychological condition.

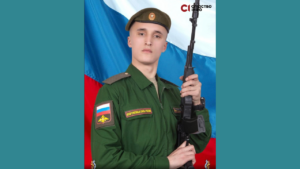

Court hearing in one of the courts of the Russian Federation

Many Ukrainian soldiers during “court sessions” in Russia or the occupied territories do not even know that they have combatant immunity guarantees and that they are prisoners of war. On our part, we conduct educational work with the military, informing them about what they should say in various situations, especially if these processes receive any media coverage.

What are the possibilities for ensuring fair justice for Ukrainian citizens in the occupied territories and Russia? And is it even possible?

— I think it’s impossible. Because Russia cannot deviate from its overall policy of destroying Ukraine and Ukrainians. To ensure a fair trial, international humanitarian law must be applied in the occupied territories. Russia will not do this because it has already recognized these territories as its own and enshrined this in its Constitution. We see a complete disregard for international law by Russia. It does not recognize the Geneva Conventions or the European Convention on Human Rights.

The repressive machinery of the Russian Federation has gained such momentum that it cannot be stopped. Eventually, it will fall into the abyss and cease to exist, as all evil empires do. The only question is when this will happen.

Currently, judges, prosecutors, and investigators who carry out the dirty work of persecuting our citizens feel absolutely impune. Therefore, Ukraine and its citizens, who have been illegally detained in Russian prisons for years, need new arrest warrants from the ICC.

We must realize that today our state cannot ensure a fair trial in Russia; we simply do not have the tools for this. We can only intensify efforts for international pressure, impose sanctions, document violations, and also think about what we will do with the judicial processes that have taken place in the occupied territories since 2014.

In June 2023, a trial began in Rostov-on-Don involving 22 Ukrainian servicemen from “Azov,” accused of terrorist activities against Russia. Why, in your opinion, did Russia choose this specific qualification?

— Azov was recognized as a terrorist organization mainly because they belong to Ukraine’s defense forces. The main goal [of the Russians] is to use Azov and other defenders of Ukraine to spread their myth about so-called “terrorists,” “neo-Nazis,” “extremists.”

The Russian authorities have no right to try Azov servicemen on these charges. According to international law, they are combatants and, in the event of capture, enjoy combatant immunity — the right not to be tried for participation in hostilities.

During the latest “trials” of Azov members in the occupied territories of the Donetsk region, a different strategy was chosen — they are accused not of terrorism, but allegedly of shelling civilian infrastructure and residential buildings. How do you explain this change?

— I believe this is a manifestation of legal warfare. Probably, when the Russians tried the Azov members as terrorists, they realized the absurdity and weakness of their position. But if our fighters are judged for allegedly committing war crimes, it creates a certain counterbalance [against Ukraine] on the international level in future trials of war criminals. In this way, they likely want to show that war crimes during this conflict are committed not only by Russians but also by Ukrainian soldiers. They want to convey the message that “things are not so clear-cut,” you understand? However, it should be remembered that these accusations are fabricated by the Russian government.

The trial of Azov members in Russia. Photo: AP

Today, a war crime as a violation of the right to a fair trial is a gray area in international criminal law. Why has this happened?

— This crime is difficult to investigate and prove. There are very few cases worldwide regarding the violation of the right to a fair trial as a crime. We can recall isolated cases in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia concerning the Khmer Rouge regime. Another example is the case of Al-Hassan at the ICC [Malian national Al Hassan Ag Abdoul Aziz worked in the “Islamic Court” in Timbuktu and was involved in the persecution of civilians based on religious grounds and the enforcement of a policy of forced marriages]. There were several cases following World War II, including the Justice Trial during the subsequent Nuremberg Trials. Thus, there is little judicial practice and few guidelines for investigators, prosecutors, and judges. Investigating such cases is a colossal task for law enforcement and the victims of such processes.

Then does Ukraine have any chance to bring these cases to the international level and achieve a positive outcome?

— I believe so. Previously, in its reports, the ICC Prosecutor’s Office noted that crimes depriving people of the right to a fair trial likely took place in Ukraine. This is an important message from the prosecutor. Although the reports mentioned the occupied Crimean peninsula (recall numerous cases of persecution of Ukrainian citizens who disagreed with the occupation regime), I am sure the ICC prosecutor is aware of similar crimes in other territories occupied by Russia.

Tymoсhko believes that the task of Ukrainian society is to ensure that Russia’s crimes do not disappear from the justice agenda. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk

Our task is to ensure that this crime does not disappear from the agenda of international and national justice.

What is the ICC’s interest?

— I think investigating such crimes will have a positive effect on the ICC’s reputation. First, the court will have the opportunity to develop practice on this issue. These will be the ICC’s first cases where the right to a fair trial will be considered in the context of a war between two states. Second, the ICC will be able to declare to the world the role of the court, judges, and other lawyers in wars and remind everyone that all these arbitrary, political, and illegal judicial processes, disregard for international law, and verdicts based on torture of prisoners of war and civilians will not go unnoticed and that the Justice Trial can be repeated.

However, we have unfinished homework — we have not yet ratified the ICC’s Rome Statute. First of all, this is disrespectful to our society and to the victims of international crimes. We all want to see Putin in The Hague, but at the same time, we do not ratify the international treaty that is the basis for this.

Yevheniia Koroliova, journalist at MIHR

Made possible by support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.