Withdrawal from Azovstal, the terrorist attack in Olenivka, and getting married online. The story of Azov fighter Serhii Alieksieievych

On May 16, 2022, Azov fighter Serhii Alieksieievych laid down his weapon, removed his ammunition, and, along with a hundred fellow comrades-in-arms, left the Azovstal territory, the last stronghold of the defenders of Mariupol. That day marked the beginning of the largest-scale captivity of Ukrainian military personnel, officially referred to as ‘evacuation to preserve life.’

The Mariupol garrison’s withdrawal from Azovstal was observed not just in Ukraine. The news about the departure also dominated the foreign media for several weeks. The agreement between the parties stipulated the exchange of the Ukrainian defenders within 3 to 4 months. However, their captivity has extended for years. They are held under deplorable conditions, subjected to torture, and killed.

In July 2022, an explosion occurred in the colony where the Mariupol garrison was held. Around fifty people were killed and more than a hundred injured—all of them Azov fighters. Serhii Alieksieievych survived but was wounded and remains in captivity.

Serhii and Mariia’s paths crossed through psychology. In 2018, they were both studying in Khmelnytskyi—Serhii was in his first year, and Mariia was in her third. They both studied psychology. A few weeks of Facebook correspondence about psychology led to a relationship. Eight months later, they started living together, and Mariia moved from Vinnytsia to Khmelnytskyi for her boyfriend.

Serhii loved learning and discovering new things. He was interested in programming, adored motorcycles, and enjoyed repairing them.

— He was passionate about self-improvement. He was always reading something. Whenever he had a free moment, he would grab a book. Serhii loved Ukrainian history and knew it well, which might be why he chose to defend Ukraine, — Mariia Alieksieievych, Serhii’s wife, recalls.

Before the full-scale invasion, the man had planned to pursue a career in psychology. However, he did not have time to get his bachelor’s degree before the war broke out.

— He also dreamed of getting a master’s degree, so the university is waiting for him to return, too, — Mariia continues.

In civilian life, Serhii was friends with the guys from the Azov unit. He mentioned that the fighters there were well-motivated and would always cover for each other.

— I remember his words clearly. He said that no matter what happened, he wouldn’t be afraid on the battlefield with these people, — his wife recalls.

Serhii Alieksieievych, a soldier of the Azov Brigade

That’s why, even before the full-scale invasion, Serhii joined the Azov unit, where he combined military training with studying psychology. He spoke little about his service, only mentioning the inevitability of a major war. He hadn’t anticipated it on such a scale, though.

At the beginning of 2022, Serhii was at the Azov base in Urzuf. One day, he called Mariia, instructing her to withdraw cash, buy non-perishable groceries, and stock up on water. Although the young woman didn’t fully understand the reason behind his request, she complied and prepared everything as he asked.

At dawn on February 24, 2022, she received a message from Serhii asking her not to call him. The guy assured her he was fine and promised to reach out as soon as a chance occurred.

— I remember waking up around six in the morning, seeing the message, not understanding it, and going back to sleep. When I woke up again about an hour and a half later, I saw the news. I knew a war was coming, but I wasn’t mentally prepared. Like everyone else, — Mariia recalls.

Whenever he had the chance, Serhii would send messages. Sometimes, days would go by without any SMS. Mariia didn’t know who to contact to find out the information. She wasn’t sure if Serhii was in Mariupol, as he hadn’t shared details with her to avoid causing unnecessary worry.

— Sometime in March, I saw an interview with Azov commander Denys Prokopenko. He mentioned that all the Azov fighters had moved to Mariupol, so I realized that Serhii was indeed there, — Mariia Alieksieievych recollects.

Got married online

“Let’s get married after the victory”. These were the words Serhii told Mariia when the full-scale war began. She agreed.

— We had been discussing our future for a long time and planned to get married, but first, we wanted to complete our education. However, the war changed everything. Serhii assured me that everything would be fine and he would return soon.

However, the situation in Mariupol was becoming increasingly dire with each passing day. Communication was deteriorating, and the Russians were encircling the city.

On April 20, Mariia received a message from Serhii. He had found out that it was possible to get married remotely. The girl agreed. Serhii’s brother-in-arms, who then happened to be in Khmelnytskyi, helped with the formal issues.

— At that time, the law allowing military personnel to marry remotely had just been passed. Serhii’s friend helped me find a registry office that would agree. We communicated with a lawyer and prepared the documents. The whole process took about a week.

Serhii was supposed to connect via Zoom or record a video where he would state his and Mariia’s personal information and confirm his intention to marry. However, communication with him was lost. Mariia didn’t know what to do.

Alieksieievych got in touch on April 27, assured Mariia that he was okay, and asked how things were going with the marriage process. Mariia explained what needed to be done. Serhii immediately recorded a video.

— That same day, I went to the registry office. I showed them the video, submitted the documents, and within 40 minutes, they handed me the marriage certificate, — Mariia recounts.

Having returned home, she texted Serhii, ‘We’re married.’ He was excited, and they both felt renewed strength to continue fighting. Mariia believed that Serhii would soon make it out of Mariupol and they would be together.

But on May 13, she received his last text message, saying that the connection was unstable, he was fine, and he might not be able to write for a long time. There was no single word to mention of Azov preparing to leave Azovstal.

The evacuation that turned into captivity

When news emerged that the defenders of Mariupol were surrendering, many relatives did not believe it—Russian propaganda Telegram channels frequently spread such information during the 86 days of fighting for the city. Official confirmation came around midnight on May 16, 2022. However, the departure from Azovstal was called an evacuation rather than captivity. On the first day, they evacuated the severely wounded—around 300 people, most of whom were taken to a hospital in the occupied Novoazovsk. The others went to Olenivka, a colony in the Donetsk region, where the Russians had set up a camp for prisoners of war. On May 20, 2022, the Azov commanders and officers left Azovstal. The defense of Mariupol had come to an end.

— During those days, I watched videos revealed by the Russians but didn’t see Serhii in any of them. I didn’t know if he had made it out of Mariupol.

Mariia received confirmation that Serhii was alive at the end of May when the first video from Olenivka appeared, and she recognized her husband among the many Ukrainian prisoners of war. Since that day, Mariia began her struggle to bring her husband home.

— I began calling the military unit to gather information and contacting all the government agencies.

Mariia learned that Serhii had left Azovstal on May 16 and was wounded in the left leg. The bullet stuck in the bone and couldn’t be removed at the ‘Zaliziaka’ (a medical facility in one of the bunkers at Azovstal).

Withdrawal from Azovstal. Photo: Russian Ministry of Defense

Then, on May 16, no representatives from the International Committee of the Red Cross were present, and none of those who exited that day were registered with the organization. Several months later, Mariia tried to contact the ICRC representatives to get information, but she received no response.

— I received a call in July saying they had no information about Serhii. When I asked how that could happen, they said they didn’t know. Later, we found out they weren’t in Mariupol that day, — Mariia recounts.

Mariia filled out a prisoner of war card on her husband’s behalf and waited again. Some Azov prisoners could call their relatives, but she received no news from her husband. The wife sought ways to contact him but was told it was impossible.

On July 29, 2022, in the morning, she stood in line at the State Migration Service to change her surname after the marriage. Out of habit, she checked the news and saw a report about the shelling of the Olenivka detention colony.

— At first, I didn’t believe it and hoped it was just another Russian manipulation, — Mariia recalls. — But then videos appeared showing the barracks with body fragments.

The woman began calling the ICRC, the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, and the SSU [Security Service of Ukraine], but all the hotlines were overloaded. Eventually, she reached the ICRC, who informed her that their team was in Donetsk and would go to Olenivka to check everything and start identifying the bodies. However, this didn’t happen. Instead, families continued to monitor the news, and lists of the wounded and dead began to appear.

— I immediately refused to look at the lists of the dead—it was too frightening. But I found Serhii in the list of the wounded. At first, I felt relieved—he was alive. But then doubt set in because those lists weren’t official, and we had no confirmation. Additionally, there was information that several people had died on the way to the hospital, — Mariia Alieksieievych recounts.

The next time Mariia saw her husband was on August 3 on Russian television. He was in a hospital, and Russian journalists asked him what he remembered and how the explosion happened. Serhii replied he heard two explosions. After the second one, everything started burning, and they began to escape from the barracks. Outside, the convoy opened fire on them. The shooting stopped when they realized the prisoners were wounded and posed no threat. Mariia saw her husband had lost a lot of weight and appeared anxious and exhausted.

Serhii Alieksieievych was wounded during the Olenivka prison attack. Photo: Russian media

— I sent those videos to everyone. The Coordination Headquarters told me there were no confirmed details about when the videos were recorded, and the ICRC assured me again that as soon as Russia granted access, they would visit everyone. In those days, conversations were arduous, — the wife of the wounded Azov soldier recalls.

Two years of anticipation

Based on unconfirmed information, Serhii Alieksieievych suffered an amputation of his big toe and shrapnel wounds. A month later, he was returned to Olenivka, after which the traces of the man were lost. On September 21, 2022, one of the largest prisoner exchanges took place, involving many defenders of Mariupol, including survivors of the Olenivka terrorist attack. However, Serhii was not among them. The Azov prisoners were transported in groups from Olenivka. Some were left in the occupied Donetsk region, and the rest were taken to the Russian Federation.

Despite numerous videos from captivity and testimonies of his released comrades, Serhii did not have the status of a prisoner of war for over a year, even after being wounded in the Olenivska detention colony. Throughout this time, he was classified as missing. His status was changed to ‘prisoner of war’ only in June 2023.

Mariia Alieksieievych has been fighting for her husband’s return home for two years

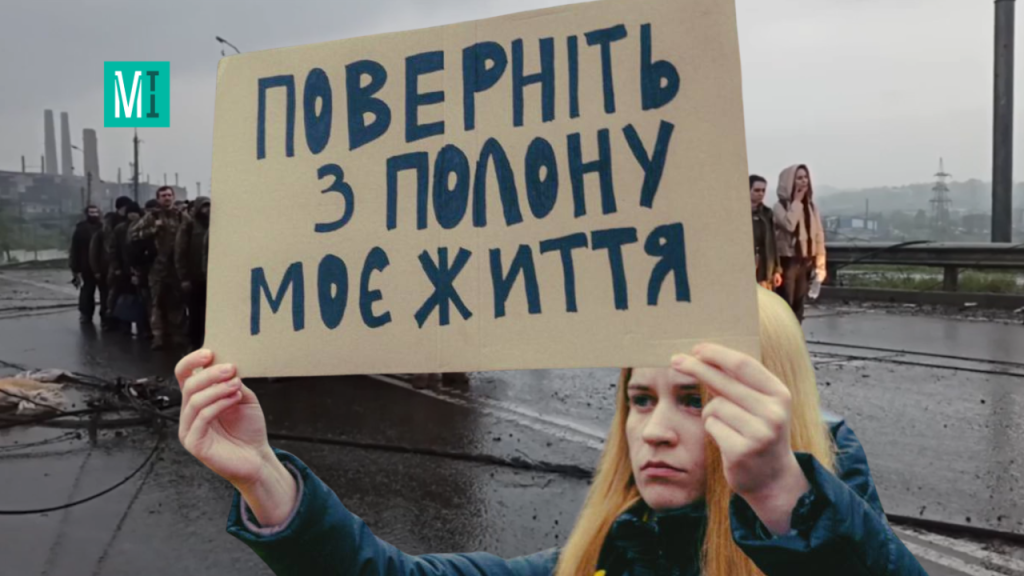

Following the events of July 29, 2022, relatives of the deceased and wounded Azov fighters united in the Olenivka Community. They talk together to expose the war crimes committed by Russia and strive to bring their loved ones home.

— I feel ashamed of the deceased and wounded and all the defenders of Mariupol that we stayed silent for so long. We were told that public statements would only harm the cause, and there were relevant organizations that would handle it. However, neither the UN Commission nor the ICRC achieved anything. For a while, Olenivka was merely forgotten, — Mariia Alieksieievych explains.

The Olenivka Community continues its fight to secure the release of severely wounded Azov fighters. They call for new ways to exert pressure on Russia, as each day in Russian captivity reduces the chances of recovery from wounds and endangers the lives of Ukrainian defenders.

This project is implemented with the support of the Veteran Hub. The organization may not share the views expressed within the project.