No Evidence Needed, Just Four Letters: Azov. Prisoners of War Sentenced in Rostov-on-Don

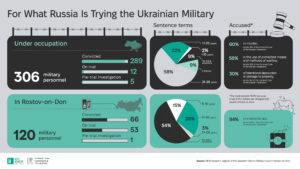

The Southern District Military Court of Rostov-on-Don has handed down sentences to 24 current and former members of the Azov Brigade. They were sentenced to between 13 and 23 years of imprisonment, all to be served in maximum-security penal colonies. Eleven were tried in absentia, and one died in a pre-trial detention center.

Behind the glass in the courtroom sat 12 men of various ages. The youngest, Artur Hretskyi, is 22 years old; the oldest, Oleh Tyshkul, is just two days away from turning 56. All of them were captured between March and April 2022, either during the battles for Mariupol or while attempting to leave the besieged city.

Preparation for a Landmark Case

It was evident even before the mass capture of Azovstal defenders that the Russian Federation intended to prosecute members of the Azov Brigade. As Russian forces gradually seized control of Mariupol, they searched for anyone who might have served in Azov. Numerous individuals were detained: some, like dog handler Yaroslav Zhdamarov and soldier Artem Hrebeshkov, were captured while attempting to leave the city; others, like driver Oleksandr Irkha, were taken from their homes.

“We lived near the Ilyich Metallurgical Plant in Mariupol. After the Marines surrendered on March 12, 2022, the Russians began clearing the city. All men were detained for filtration purposes. They were looking for those named by their neighbors. The neighbors knew who had served and where. My father was a senior mechanic and tank driver. Almost immediately, they came to our house for my father based on an informant’s tip. But he wasn’t home, so they detained me and took me to the village of Bezimenne for filtration. My father and I met there a few days later. It was between April 17 and 19, 2022,” says Andriy Irkha, the son of Oleksandr Irkha.

Despite having previously served in the police, Andriy passed the filtration process. However, Oleksandr did not: the Russians found out that he had served in the Azov Brigade.

“He failed to clean up his social media accounts as he didn’t remember the passwords, and his pages contained information about his unit from the time he served,” says Andriy Irkha, the son of Oleksandr Irkha.

Oleksandr was then taken to the so-called Organized Crime Department in Donetsk, where his trail went cold.

Victoria Zhdamarova, the wife of Yaroslav Zhdamarov, who was detained during the filtration process at the end of April 2022, was also unable to locate her husband.

“Yaroslav’s documents were checked, and they asked him whether he had served and where. They took his passport, told him to step aside, and made phone calls, sharing his personal information over the phone. After the conversation, they said that they would come for him in the afternoon to take him for interrogation. They did not give back his passport.”

Ultimately, Zhdamarov, like Irkha and two dozen other “suspects”, ended up in the Donetsk pre-trial detention center. While they were held in the basement, the Russians were setting up prison cells on the stage of the partially destroyed Mariupol Drama Theater, preparing to stage a show trial for the Azov fighters. The trial was expected to begin in August 2022.

Yaroslav Zhdamarov in the glass box during trial. Photo: Mediazona

The trigger for this process was the fact that on August 2 of that year, the Russian Supreme Court declared the Azov Brigade a terrorist organization and banned its activities in Russia following a lawsuit from the General Prosecutor’s Office. The trial lasted a month, partially in closed sessions, with “witnesses” being so-called Russian human rights activists. One of them claimed that “the regiment practiced cannibalism”.

However, the trial in Mariupol never began. The indictment – an 855-page document – was finalized in the autumn and signed by Vadim Kosyrev, a “senior investigator for particularly important cases” of the so-called “General Prosecutor’s Office of Donetsk People’s Republic”, and approved by “Deputy Prosecutor General” Roman Bilous. The document alleged that in 2014, the Ukrainian government created a “structured, militarized and organized group”, i.e. the Special Operations Battalion “Azov”, whose members were portrayed as adherents of “neo-Nazi and National Socialist ideology”, who “harbored hatred and hostility toward residents of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Russian Federation because of their Russian ethnicity and political beliefs.”

The detained members of the Azov Regiment continued to be held in Donetsk, where so-called “investigators” conducted interrogations and investigative procedures. In 2023, the case files were transferred to Rostov-on-Don in Russia, along with the accused. They were charged with violent seizure of power (Part 4, Article 35, Article 278 of the Russian Criminal Code) and with organizing the activities of a terrorist organization (Part 1, Article 205.5 of the Russian Criminal Code). Some were additionally accused of undergoing training for terrorist activities (Article 205.3 of the Russian Criminal Code).

United by Azov

The first court hearing took place on June 14, 2023. The prosecutor read out the charges against 24 individuals. However, only 22 appeared in the courtroom. Lieutenant Davyd Kasatkin, call sign “Khimik”, returned to Ukraine as part of the prisoner exchange in September 2022, and Senior Soldier Dmytro Labinskyi, call sign “Odesyt,” was repatriated in May 2023

Dmytro Labinskyi was captured on March 31, 2022, when a helicopter evacuating wounded soldiers from Azovstal was shot down by Russian forces. He and one other Ukrainian serviceman survived the crash. Davyd Kasatkin surrendered at Azovstal on May 20, 2022. Initially held in Olenivka, he was later transferred to Makiivka. Russian propagandists attempted to fabricate a case alleging that Kasatkin had published a post threatening the President of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. Kasatkin was exchanged on September 21, 2022.

Of the active-duty personnel, eight women and five men remained in custody.

The women were exchanged in September 2024. At that time, eight cooks returned to Ukraine, namely Olena Avramova, Nina Bondarenko, Olena Bondarchuk, Vladyslava Maiboroda, Iryna Mohitych, Liliya Pavrianidis, Liliya Rudenko, and Maryna Tekin. Alongside them, civilian detainee Nataliya Holfiner – the former head of the Azov Regiment’s food storage facility in the village of Urzuf – was also released.

The Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) spoke with several recently released detainees. They try to avoid recalling their time in captivity, and speak shortly about the court proceedings.

“We were prosecuted solely for being part of Azov without any evidence of actual crimes,” said one of the women.

Among the 22 individuals accused of terrorism were eight women who had served as cooks in the Azov Battalion. They were exchanged in September 2024. Photo: EPA/UPG

Another woman recounted: “I asked them, ‘what crime did I commit? What evidence do you have?’” The response was blunt: “You were member of Azov.”

“It’s completely absurd to put someone on trial for cooking food for soldiers. The prosecutor read out our testimonies and then showed videos about Azov from the Internet. That was their evidence against us. But how can a video from 2014 be considered evidence when none of us were even serving back then? We have a bloke who was only 11 years old in 2014, he is 21 now. How could he possibly have been involved in what they were showing in that footage?” said a former prisoner of war.

“They kept asking me if I knew how to shoot. I never denied that I served in Azov, and I never claimed to be a civilian. Yes, I served. I was a cook. When I asked how exactly I, as a cook, have been seizing power, they told me: ‘It’s none of your business, it’s for the case file,” continued the released prisoner.

“24 TV channels were present at the first hearing. And it was absurd: they portrayed us, Azov members, as terrifying monsters, but in reality, we were emaciated, filthy, and exhausted,” said the Azov representative.

According to the indictments reviewed by MIHR, the women, upon joining the Special Operations Regiment “Azov”, were allegedly made aware of the organization’s so-called terrorist tasks and objectives. The documents claim that, “fully understanding the public danger and unlawful nature of their acts, and acting in concert with other members of the terrorist organization to achieve the goals of the Special Operations Regiment “Azov, they prepared and distributed food to members of this terrorist organization.

The servicemen Oleksandr Merochenets, Oleksii Smykov, Mykyta Tymonin, Artur Hretskyi and Azov’s logistics officer Oleh Zharkov, remain on trial.

Another serviceman of military unit 3057, Oleksandr Ishchenko, died in July 2024 while in pre-trial detention center No. 5 in Rostov. He had suffered from serious heart conditions and had already experienced a heart attack while in custody in Rostov. Despite his deteriorating health, the Russian authorities refused to release him. This likely led to another heart attack. According to witness accounts, one day Ishchenko fell seriously ill in his cell, but fellow prisoners of war were unable to summon medical assistance for a long time. What happened after prison medics finally arrived remains unclear. However, it is known that when Oleksandr Ishchenko’s body was returned to Ukraine, it showed signs of trauma: broken ribs and injured chest. As noted in the forensic medical report, these injuries were inflicted by a blunt object.

Azov member Oleksandr Ishchenko, who died in Russian captivity. Photo: Mediazona

All the others, including Irkha and Zhdamarov, are currently considered civilians. Each of them had left the army before the onset of the full-scale invasion.

A Failed Attempt at a Defense

“There is no point in hoping for justice in Russia. When I asked for a lawyer, I was told, ‘You have a university degree, so you can defend yourself,’” said one of the women who was released.

During trial, the defendants were represented by Russia-appointed lawyers. Only a few had counsel they had been able to arrange independently. These lawyers made efforts to draw the court’s attention to procedural violations and inconsistencies. Whether those efforts made any real difference remains unclear.

Key to the case was the defense’s consistent argument throughout the proceedings that there was no connection between “Ukrainian paramilitary unit “Azov” referenced in the Russian Supreme Court ruling, which designated it a terrorist organization, and the 12th Special Operations Brigade “Azov” of the National Guard of Ukraine, operating under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. All of the servicemembers, both current and former, had signed contracts with the latter, namely military unit 3057. Experts engaged by the prosecution failed to shed light on this inconsistency.

The Show Trial of Azov Brigade Servicemembers Photo: Mediazona

“I insist that court proceedings failed to establish any evidence that the Special Operations Regiment “Azov” of the National Guard of Ukraine under the Ministry of Internal Affairs was ever designated a terrorist organization by any entity, including judicial bodies of the Russian Federation or the so-called ‘DNR’. No proof has been presented showing its legal succession of the volunteer paramilitary formation known as the Azov Regiment, “ said the defense attorney for one of the Azov servicemembers. “The indictment itself,” she added, “is a patchwork of inconsistencies dragging in horses, people, cooks, and soldiers alike, and is just a piece of paper.

Secondly, how can a Russian court claim jurisdiction over events that, if they occurred at all in 2014 – 2015, took place on the territory of a foreign sovereign state, i.e. Ukraine?

The Russian Federation itself recognized all territories of Donetsk region as part of Ukraine. So why it decided that it had the right to interfere?” the defense attorney continued. She went on: “Hrebeshkov served in the National Guard of Ukraine from 2018 to 2021. He had every legal right to serve in 2022 as well, but the circumstances were such that his service ended in 2021. How can he be accused of something that we ourselves considered entirely legitimate at the time? Even the so-called “DNR” was treated as part of Ukraine’s Donetsk region.”

Final Statements in Court

“It seems to me that no evidence is actually required in this courtroom, just four letters that appear in the name of the unit: ‘Azov,’” said former marksman Oleksandr Mukhin during his final statement before the court.

The delivery of final statements in the so-called “Azov case” spanned two days. On March 5, 2025, statements were given by Yaroslav Zhdamarov, Oleksandr Merochenets, Oleksii Smykov, and Oleh Myzhhorodskyi. On March 19, 2025, the court heard statements from Oleksandr Mukhin, Oleh Zharkov, Anatolii Hrytsak, Oleksandr Irkha, Artur Hretskyi, Oleh Tyshkul, Mykyta Tymonin, and Artem Hrebeshkov.

Oleh Myzhhorodskyi. Photo: Mediazona

In summary, all of the accused spoke to the absurdity of the charges and lack of evidence, but none denied that they were, at some point, the serving members of the Azov Regiment.

MIHR managed to hear the voices of the defendants. Some, like Oleksandr Merochenets, spoke for over an hour, others, like Oleksandr Irkha, uttered just a few words, calling the charges “nonsense.” Artur Hretskyi declared: “I do not admit guilt, and I do not recognize the Russian Federation’s right to try me.” Oleh Tyshkul refused to deliver a final statement altogether, and said: “I do not recognize this court, and I do not intend to speak.”

“I am an active duty serviceman who was captured and detained. The prosecutor claimed that the defendants do not have the status of prisoners of war, even though there are active military personnel among us. I am an active duty soldier, and the duty of a soldier is to defend his country when it is attacked. That’s exactly what I did. I did not cross a single inch of my country’s border. I defended my homeland, the place where I lived, studied, and built a family,” said Oleksandr Merochenets.

Oleksandr Merochenets. Photo: Mediazona

“I’ll be brief. I defended my homeland and fulfilled my duty to my country. I hope for a fair trial, but considering everything I’ve endured since being taken prisoner, namely the absurd accusations of attempting to seize power and of terrorism, there is little hope left for justice in this court. In these circumstances, only a full acquittal would be just and lawful,” said Oleksii Smykov.

Oleksii Smykov. Photo: Mediazona

“There’s an old Soviet film called Officers. It’s in black and white with one of the main roles played by Vasyl Lanovyi. His character said: ‘Yes, brother, there is such a profession – to defend your Motherland.’ Four men who defended their homeland now sit here among us. They are service members, they fulfilled their duty, their oath, and I am grateful to them for that. Thanks to them and to the thousands of others who stood up to defend their country, my wife, whom I’ve been married to for 30 years, and my 12-year-old child will have a chance to return home,” said Oleh Zharkov. He then added: “What they tried to do here was to force a square peg into a round hole.”

Oleh Zharkov. Photo: Mediazona.

“To begin with, I didn’t want to speak at all. “First of all, I don’t want to justify myself. Second, you know, I’m a lifetime military man. I have dedicated my entire life to military service. I rose through the ranks from a private to the commander of a a special forces unit. I retired in 2008 aged 32. Back then, the service time was counted as one year for every three, which was not the case for such units in other CIS countries. The unit I served in specialized in peacekeeping operations. Over the course of my military career, I served in uniform in 18 countries, and took part in missions in four of them, including Bosnia, Kuwait, Kosovo… It doesn’t matter now. What I’ve come to understand is this: I can’t even begin to describe what I feel and what I’ve lived through, and what your country did to my country and to my home. How my wife was shot on the road in front of me. How these so-called ‘liberators’ came into my house and looted everything to the last penny. How they threw me in prison for three years… Now it’s the fourth,” said Lieutenant Colonel Anatolii Hrytsyk, who served in staff positions in the Azov Regiment between 2015 and 2019.

Anatolii Hrytsyk (on the right) Photo: Mediazona

The Verdict: Active Duty Servicemen Get the Lengthiest Sentences

On the morning of March 26, 2025, all twelve men were brought from the pre-trial detention center to the courtroom. They were led into the glass defendants’ cage in shackles, a detail clearly visible in photographs taken in the courtroom that day. It is well known that they were transported in chains secured to both their hands and feet, but it was the first time they were brought into the courtroom in such a visibly humiliating manner. It looked like the intention was to present them as “real terrorists” before dozens of cameras.

The chains restraining the Azov servicemen are clearly visible in this photo. Photo: Mediazona

Presiding judge Vyacheslav Korsakov announced the verdict: all 24 defendants were found guilty and sentenced to lenghty terms of imprisonment. Dmytro Labinskyi, Davyd Kasatkin, and Oleksii Smykov were sentenced to 23 years of imprisonment in a maximum-security penal colony. Oleh Tyshkul, Oleksandr Mukhin, and Yaroslav Zhdamarov were sentenced to 22 years. Oleksandr Merochenets, Mykyta Tymonin, and Artur Hretskyi also received 22-year sentences. Artem Hrebeshkov and Oleksandr Irkha were sentenced to 20 years each. Oleh Mizhhorodskyi and Oleh Zharkov were sentenced to 17 and 13 years of imprisonment, respectively.

The women who had already been released were sentenced to 13 years of imprisonment in a general-regime penal colony, while Liliya Rudenko and Nataliya Holfiner received a 14-year sentence each.

“Russia is not merely prosecuting particular persons. It is targeting those segments of the Ukrainian population who resist the aggression. The charges are not based on evidence of terrorist activity, but rather on affiliation with a formation designated as illegal. In essence, people are being sentenced for taking part in combat operations, which is a direct and lawful consequence of their duties as military personnel,” says Andrii Yakovlev, attorney and managing partner at Umbrella Law Firm, and expert in international humanitarian law.

The lawyer emphasizes that the classification of terrorism is applied not according to actual circumstances, which define terrorist activity globally, such as acts intended to intimidate civilian population or pursue political or other aims. Instead, the Russian Federation disregards the fact that the primary objective of combat operations for combatants is to achieve military advantage, typically by attacking military targets. Therefore, a soldier participating in combat operations may not be a terrorist by definition.

The Russian prosecution relies on the ruling of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of August 2, 2022, whereby the Azov Regiment is deemed a terrorist organization.

Russia’s judiciary has labeled as terrorist an official unit of Ukraine’s Defense Forces,” adds Andrii Yakovlev. “But how can an organization be considered terrorist when it is engaged in a legitimate war of self-defense and resists aggression?”

According to the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (the Third Geneva Convention), prisoners of war may not be prosecuted or punished merely for their participation in hostilities, provided that their actions do not contravene the laws and customs of war.

Can we identify any violations of the laws and customs of war based on these legal qualifications? The prosecution fails to distinguish between civilian and military targets, and determines neither the necessity of the attack, nor its proportionality. The entire trial is reduced to the simple fact of being affiliated with Azov,” notes Andrii Yakovlev.

He further emphasizes that the judicial proceedings against both former and active members of the Azov Regiment were initiated in the autumn of 2022 in the Donetsk region, where the prisoners of war were prosecuted under the criminal code of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic.”

From the outset, the Russian Federation deprived the defendants of their right to a fair trial. It subjected prisoners of war to prosecution not under Ukrainian criminal law, as is required under Article 64 of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (Fourth Geneva Convention), but under a hybrid legal framework it unilaterally imposed. This framework is composed partly of outdated Ukrainian legislation, which Ukraine had previously discarded due to its inquisitorial nature, and partly of Russian criminal law,” the expert notes.

The process was later reclassified under the Russian Federation’s criminal code and conducted in accordance with its domestic legal procedures and practices.

In this way, the so-called “Azov trial” serves as a stark illustration of the violation of fundamental principles of the right to a fair trial, as enshrined in Article 75 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.

First and foremost, this concerns a violation of the right to legal defense. The accused were coerced into signing documents without the opportunity to review their content or to object, as they were subjected to intense torture aimed at breaking their will and extracting statements desired by the investigators.

The fact that Russian defense attorneys are formally involved in these court proceedings does not improve the situation. The political realities in Russia prevent lawyers from effectively carrying out their professional duties – otherwise, they themselves risk facing prosecution or falling under the influence of political authorities,” explains Yakovlev. In the trials of Ukrainian prisoners of war, not only are defence witnesses not summoned, but the prosecution witnesses are also not examined.. The evidence presented by the prosecution is either not scrutinized by the defense or cannot be verified at all,” adds Yakovlev.

Secondly, another serious violation lies in the absence of judicial independence and impartiality.

“Courts in Russia operate under the direct political control of the Kremlin, rendering judicial proceedings inherently biased. This is not an independent judiciary, but effectively an extension of the executive branch that pursues politically motivated objectives,” the expert concludes.

Thirdly, this trial violates a fundamental principle of justice,i.e. the presumption of innocence. The accused were presumed guilty from the outset solely on the basis of their affiliation with “Azov.”

All statements obtained from the accused during the investigation were extracted through threats and torture. In other words, the evidence used in the trial was obtained in flagrant violation of human rights”, says Yakovlev.

“I saw bags over heads, wires attached to different parts of the body, broken ribs, shattered kidneys, people beaten to death, starvation, and no medical assistance for over a year. People with rotting legs and arms, infested with lice, and still being beaten,” said Mykyta Tymonin during the trial.

The “Azov case” is just one in a long chain of prosecutions targeting members of the unit. In early March 2025, the head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, Alexander Bastrykin announced that verdicts had already been issued against 145 Azov fighters. Dozens more cases are still pending in court.