A Russian captive since March. What has happened to the abducted journalist Dmytro Khyliuk

Kozarovychi, a village in Vyshhorod Rayon, Kyiv Oblast, was occupied on February 26, the third day of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. Locals say they first heard the movement of huge columns of Russian military equipment, almost immediately followed by Russian troops’ entry of the village. They began quartering soldiers, setting up roadblocks, making trenches in yards, and detaining civilians. On March 3, the Russians captured the well-known journalist and UNIAN correspondent Dmytro Khyliuk in the yard of his own house. At first, he was held in occupied Dymer and later transferred to a pretrial detention center in Russia.

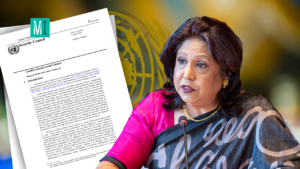

Dmytro Khyliuk

“They waited for me in the yard with assault rifles, shot over their heads, held me captive in Dymer”

Since the invasion started, Dmytro Khyliuk continued living at home and working at UNIAN. Still aware of the danger, he refused to leave pointblank, according to the journalist’s family and friends. However, he did not find it possible to move from Kozarovychi at that time, as he had to take care of his parents he lived with. On March 1, Dmytro posted on social media that the occupiers had already taken the village and regularly went from house to house, looking for food and water. He told his friends on the phone that he was no longer able to leave, artillery shells were constantly spotted over the village. On that same day, the aggressors searched his house.

Kozarovychi

“They came, asked us to go outside, walked around looking for something. They took my and my wife’s phones that were lying in plain sight. Dima’s phones were somewhere else, so they did not see them,” Dmytro’s father Vasyl Khyliuk tells MIHR.

Dmytro Khyliuk’s parents, Halyna and Vasyl Khyliuk

On March 2, the day after the search, a Grad [MRLS] missile hit the journalist’s house. Fortunately, it was not damaged beyond repair, and its occupants survived. However, broken windows and doors made the family move to a neighbor’s house.

“We decided to move to our neighbor. We packed our things, moved, stayed the night there, and decided on March 3 to go home and see how our house was doing, and the damage, in the light of day. As we reach our house, five soldiers of Asian appearance rush at us near the house and start shouting, “Hands up! On the ground!” They put us on the ground, searched us, took off our boots, even shot over Dima’s ear. Then they picked us up, put jackets over our heads and walked us away,” continues Vasyl Khyliuk.

The wall of Khyliuk’s house broken by a Grad missile

According to him, it was not clear at first where exactly the aggressors were taking the hostages, but later the journalist’s father realized that these were warehouses in Kozarovychi.

“We were separated,” the father recalls. “I was downstairs, Dima was taken to the second floor. Then I was transferred to a garage and locked up. I heard explosions, and then several dead bodies were dumped with me—their soldiers killed by our artillery.”

A Russian tank drove into a house next to Khyliuk’s home

“A Russian soldier told us, ‘Don’t worry, Dima will return home after the war’”

From March 3 to 8, Dmytro and his father were on a warehouse site in Kozarovychi. After that, they were moved to Dymer.

Kozarovychi house after the occupation

“Suddenly, during the night of the 8th [of March], they opened the door, put me into a military truck with other guys, and I heard a voice. That’s how I found out that it was Dima. We were taken, as we later got to know, to Viknaland, a business in Dymer, and thrown into a compressor room, where other people were already kept. They locked the door, leaving us on the cement floor. It was dirty all over, dark,” says Vasyl Khyliuk.

During an investigation in the occupied part of Kyiv Oblast in March, MIHR journalists found out that Dymer was a center for holding hostages. Ukrainians were kept in two detention facilities—a foundry and the Viknaland plant. Another witness interviewed by MIHR, Oleksandr Ivancha has said that the last time he saw journalist Dmytro Khyliuk was on March 11. “They took him out, and I never saw him again,” he says. Dmytro’s father also says that Dmytro was taken out of Viknaland on March 11. “I even asked what was happening, and when Dima would return home. One Russian soldier said, ‘Don’t worry, he will be back when the war is over.’”

According to Dmytro’s father, prisoners were taken to occasional interrogations, to be asked about their job and military personnel they personally knew. When asked about Dmytro’s job, Vasyl Khyliuk said he was a teacher. However, he found out later from a talk with his son that Dmytro had told the Russians he worked as a UNIAN journalist.

Dmytro Khyliuk’s father was also released on March 11. Instructed by the Russians to say that “the 83rd let him go” (probably the 83rd Guards Air Assault Brigade of the Russian Armed Forces from Ussuriysk, which took part in the offensive on Kyiv Oblast in February 2022) at roadblocks in Kozarovychi, he reached Kozarovychi on foot. “A total of 9 people were released. But I couldn’t get into my house, where Russian soldiers were already quartered. They wouldn’t even let me into the yard. I couldn’t get to my neighbor’s house, where my wife Halyna Yukhymivna was staying, either. So, I spent the night in a barn,” recalls Vasyl Khyliuk.

The aggressors left someone’s car in Khyliuk’s garage

“Dmytro was relocated to Pretrial Detention Center No. 2 in Bryansk Oblast—I got a letter from him saying that he felt well”

Kozarovychi was de-occupied on March 31. At night, the aggressors left in an organized column towards Ivankiv. Soon, Ukrainian investigators arrived in the village and took Vasyl Khyliuk’s testimony of the capture and abduction of Dmytro Khyliuk. As soon as in May, prosecutor Oleksandr Vinnytskyi, of the Prosecutor General’s Office, came to Kozarovychi for an additional interview of the journalist’s father. The Prosecutor General’s Office commenced criminal proceedings into the abduction of civilians within Dymer amalgamated territorial community. In the proceedings, journalist Dmytro Khyliuk and his father figure as victims. The criminal proceedings are under Part 1, Article 438 of the Criminal Code. This article covers violations of the laws and customs of war, including cruel treatment of prisoners of war or civilians, deportation of civilians for forced labor, looting of items of national value in the occupied territory, use of means of warfare prohibited by international law, other violations of laws and customs of war described in international treaties.

Dmytro Khyliuk’s relatives did not know about his whereabouts for a long time. But in late April, the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War called to say that Russia had confirmed that the journalist was being held in the Russian Federation.

Back in May, a MIHR journalist managed to talk to Ihor Shostak, a Kozarovychi resident released through exchange. He said, “The guys who were with me in the cell heard the name Khyliuk there, in the pretrial detention center.”

This is Pretrial Detention Center No. 2 in Novozybkov, Bryansk Oblast, which recently featured in a MIHR piece on hostages — the Levytskyi brothers.

In August, thanks to the ICRC, Dmytro Khyliuk’s parents got a letter from him in an envelope stamped “Pochta Rossii.” The letter included one sentence only, “My dear mother, father, I am alive, healthy, everything is fine,” and the date below—April 14. The parents wrote an answer and passed the letter, but nobody knows what became of it, because there are no guarantees that the ICRC managed to arrange for the delivery of letters to abducted Ukrainians.

It is not known, either, whether Dmytro Khyliuk is still being held in Novozybkov. After all, as MIHR was told by witnesses released from Russian captivity through exchanges, the Russians move prisoners between different pretrial detention centers. For example, civilians from Bryansk Oblast were transferred to a pretrial detention center in Kursk, a labor camp in Kamensk-Shakhtynskyi, Rostov Oblast, and detention facilities in Sevastopol.

Violation of human rights and humanitarian law. Can journalist Dmytro Khyliuk be released through exchange?

A lawyer and Dmytro Khyliuk’s attorney, Oksana Mykhalevych explains that there is international human rights law and there is international humanitarian law. Both are violated in the case of Dmytro Khyliuk.

“Civilians may not be taken prisoner. Military personnel may be captured, and civilians may be detained to check whether they help the military, oppose military aggression or the ‘special operation,’ as they put it. The Geneva Convention allows Russians to detain a civilian, provided only that their human rights are respected, in particular, to a fair trial and legal protection. This is guaranteed by the Fourth Geneva Convention,” Oksana Mykhalevych tells MIHR.

That is, if the Russian Federation abode with international law, any journalist suspected of an activity (cooperation with the Armed Forces of Ukraine, for example), would be entitled to trial, an attorney, and regular consultations with the attorney.

“But this is not the case, they are simply held in a pretrial detention center, no attorney is allowed to see them, no trial takes place,” says Oksana Mykhalevych.

She notes that in March-May 2022, during exchanges, more than a hundred civilians held in Russian labor camps were released. But, as time passed, exchange procedures have changed and only apply to military personnel now. The issue of civilians remains unresolved. Oksana Mykhalevych believes that there are no clear mechanisms yet for freeing Ukrainian civilians from Russian prisons.

“Unfortunately, international law was not prepared for this. It relies on each state to adhere to the declared principles. And Russia does not follow them in general. That is, there are no legal mechanisms to handle this. There are only political mechanisms such as freezing assets, seizing property, imposing sanctions on the aggressor state, etc. But no legal mechanisms. And this poses a problem,” says Oksana Mykhalevych.

She also explains that international courts have no say here, as the Russian Federation does not enforce their judgments. An example is ECHR, with which the attorney filed a request in spring regarding the case of the abducted Dmytro Khyliuk.

“The ECHR admits our cases, but follows a general procedure in hearing them. First, a complaint is filed to see whether the convention relied on by the plaintiff was indeed violated. We complained mostly about the violation of Article 5—unlawful detention of a person. There are other violations, too. At first, we reached out to Russia, saying that such detention was unlawful. The ECHR did this (by passing on our request to the Russian Federation, — MIHR), but the Russian government does not respond. After that, we filed a complaint against a violation. But in fact, the ECHR can do nothing else,” explains Dmytro Khyliuk’s attorney.

Exchanges of civilians are subject to certain restrictions in Ukraine itself. “Under the Geneva Convention and the Universal Convention on Human Rights, such exchanges are prohibited, because in principle they had no right to capture civilians. By starting exchanges, we run the risk of them continuing to capture civilians. Russia should release them unconditionally. Is there a way to make it happen? Political pressure, and nothing else,” adds Oksana Mykhalevych.

Therefore, according to lawyers, hundreds of Ukrainian citizens will remain in Russian captivity until Ukraine devises a political mechanism for the release of civilians, and our international partners agree on a clear sanctions package against the aggressor state for the abduction and detention of civilians.

“I don’t understand why he hasn’t been released yet. We made numerous inquiries, were regularly approached in the summer by the police, the Security Service of Ukraine, parliament members, even Minister Iryna Vereshchuk. She told us not to worry, saying he would be back soon. But nothing happens after so much time, no exchange, my son is still in captivity. And we’ve been waiting for the return of our only child for so long,” says Dmytro’s mother Halyna Khyliuk.

Natalia Bohuta, MIHR