The road of death: The shooting of civilians on the Kreminna-Lyman road

“My wife said to me: ‘Look, the military are there.’ And they were lined up in a wedge, with a tank on each side. On the tower of one of the tanks, my wife saw a painted circle with a square inside it. Well, we couldn’t go back because we were going down the hill, so we went forward,” Oleksandr Drobot begins his story. He is the only civilian who survived on April 18 when leaving Kreminna towards Lyman on the Kreminna-Torske road. Around nine in the morning, together with his wife, his mother-in-law and his dog, he got into his car and set off. As soon as they crossed the border of Luhansk and Donetsk regions, they saw Russian military equipment on the right in the field.

At that very moment, their car began to be shelled. Oleksandr and his wife jumped out of the car. The door jammed on his mother-in-law’s side, the car caught fire.

“The shooting started somewhere up ahead, but they were far away, I did not see them. And then the shooting started from behind. Like in a shooting range,” the man recalls. “I tried to open the door, and I was shot in the leg—the bullet went right through. My wife bandaged my leg. Then I ran to open the door on the driver’s side, threw things out on the road, pulled my mother-in-law out. Her two legs were torn off and hanging on the skin. I dragged her into the ditch. I looked at the dog—the dog was also killed. My wife ran to get a bag with documents. And she was also shot. She couldn’t get to the ditch but fell down saying: “I’m shot in the arm.” I looked at her arm—she had a hole in the right side of her chest from something large-caliber. Then she just died. I also dragged her into the ditch, and covered her and my mother-in-law. And the car was constantly being shelled. Like a safari—shooting and shooting and shooting.”

According to Oleksandr Drobot, the shelling lasted for 30 minutes. All this time the man was hiding in the ditch. Then he crawled towards the village of Torske. In 500 meters he sat down to rest, and suddenly he saw a Zhiguli (VAZ-2106) car moving from Kreminna in the direction of Lyman. The car drove by, and then it began to be shelled. The man says that the car caught fire, black smoke coming out of it. He doesn’t know if anyone survived.

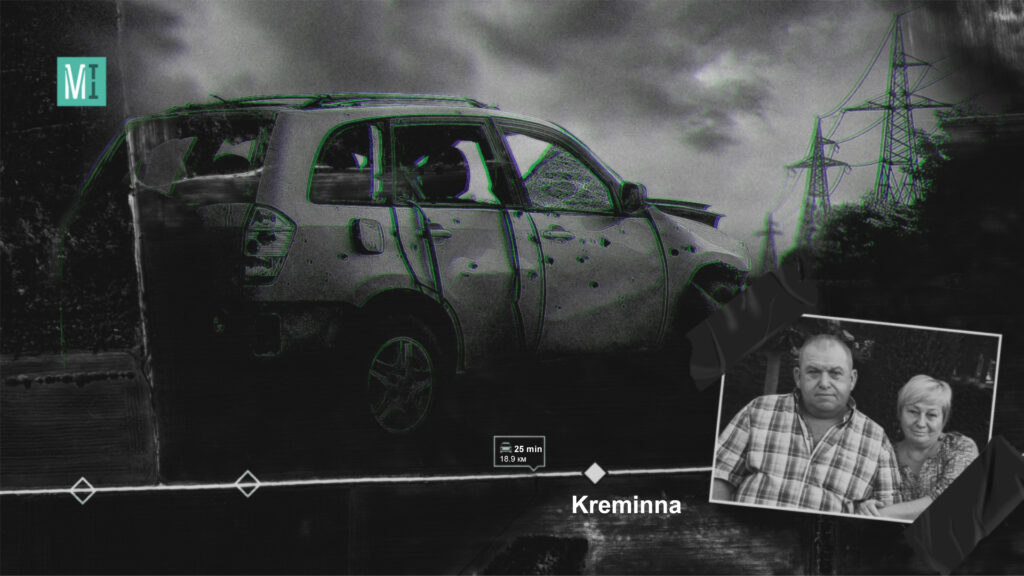

Oleksandr Drobot’s car before the shelling

When his watch read 09:38, Oleksandr got a call from his daughter. He asked her to call the rescuers. After a while, he received a call from the Lysychansk EMS saying that they would not come because the road was under fire. Then the Lyman EMS called. At first they also did not want to go, but eventually they said that the car was on its way.

“I told them not to come there because they would be shelled. And they called me later and said: ‘We have already been shelled.’ That was it, the connection with the ambulance was lost,” he says.

The man decided to wait for dusk to try to crawl across the field at night, and then walk home through the forest. However, Russian soldiers were already standing along the forest, so as soon as it got dark, he got on the road and headed towards Torske with the wounded leg.

“As I was walking, I saw the same Zhiguli completely burnt, still smoking. And then, one by one, the cars started to appear. I did not see people there; apparently, they all burned down,” Oleksandr says. “Then more and more cars. It was dark, night. I was walking with the thought that I would be killed. I saw an ambulance there. The light in the car was on, but there was no one inside. The ambulance was not burned. I walked around it and carried on. Then I saw two corpses on the road. As I went further, I saw burnt cars again. The doors were closed everywhere, so I think all the people were killed.”

According to the man, he saw a total of at least 15 destroyed cars on the Kreminna-Lyman road.

Despite the fact that it was raining that day, many of the cars were smoking, so it was clear that the cars had been shelled recently. In addition, many of them were thrown off the road—as if removed to keep them out of the way. With about 1.5 km left to Torske, Oleksandr saw people with a flashlight in the distance. They came up to the hill, shone the flashlight on the road and the field. At that time, the man hid in the bushes, where he stayed until five in the morning. He says that he could hear a mortar to his left.

“In the morning I got going again. Every second I expected to be shot,” Drobot recalls. “I saw our flag hanging on the checkpoint ahead, and an unexploded Grad shell sticking out of the asphalt. I got closer to the checkpoint—there was no one there. Then I went to the first yard I came across and called my friends. Some time later they picked me up and took me to another village.”

Oleksandr Drobot with his wife

Speaking about the circumstances of how his car was shot, Oleksandr says that they were shelled from large-caliber machine guns mounted on the turrets of tanks, as well as from assault rifles. He is sure that the military knew that they were shooting at civilians, because white flags were tied to all the doors of the car, and sheets that said “people” were pasted on the glass. In addition, single shots were fired at the car at first—like when they shoot in a shooting range. Each shot tossed the car up.

The bodies of his wife and mother-in-law lay in the open for 17 days

The village where Drobot was brought by his friends fell under Russian occupation. No one knew about him for some time, but on May 4, a local headman came to the place where he was staying and said that documents were found on the road between Kreminna and Torske. Among them was Drobot’s work record book and medical card.

“The headman said that the documents were in the commandant’s office, that they were handed over from the checkpoint, that someone was delivering bread and saw the bag with documents and took it. The commandant said that my family was killed, that it must have been Ukrainian troops who shelled them. He promised to help bury them.”

Graves of Oleksandr Drobot’s wife and mother-in-law, Kreminna. On May 5, the town’s funeral service took their bodies from the road and buried them in the cemetery.

At the same time, his in-law handled the evacuation of the bodies of Oleksandr’s wife and mother-in-law to Kreminna. He arranged with the occupation commandant’s office for the evacuation and burial of the dead, who had been lying in the open for 17 days. On May 5, the local funeral service delivered the bodies of the women to Kreminna and buried them. No documents about the death and its cause were issued to Oleksandr Drobot’s family.

This story became the starting point of the Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) investigation, in which our team set out to collect and investigate facts in four areas:

- The context around Kreminna at the time of the town’s occupation

- The place where Oleksandr Drobot’s car was shelled

- Who shelled it and from where

- Victims

Methodology of the investigation

The results of this report are based on field and remote research conducted by MIHR from June 21 to September 17, 2022. The report is based on evidence collected during personal interviews with a witness of the shelling, representatives of the central authorities, local authorities of Kreminna (Luhansk region) and Lyman (Donetsk region), military commanders who led the defense of these towns, relatives of the victims, residents of Kreminna and Lyman who managed to evacuate.

In the course of the investigation, satellite images of the area where the shelling took place, taken shortly after the murder of Oleksandr Drobot’s family members, as well as open source data about this event, relevant photos and videos were analyzed and used for this report.

The MIHR team interviewed people in person and remotely via telephone or Internet using software with audiovisual content recording capabilities. Before the interview, all interviewees were informed about who was collecting the information and for what purpose.

Throughout the investigation, the Media Initiative for Human Rights did not have access to Kreminna, Lyman and the road connecting these towns. MIHR conducted 17 interviews, including with a witness wounded during the shelling; representatives of the military command responsible for the defense of Kreminna; residents of Kreminna and Lyman who evacuated on April 18, 2022; representatives of local authorities. We also took into account other testimonies about the investigated event collected by journalists, government officials and law enforcement officers.

Some participants of this investigation agreed to speak to MIHR on condition of anonymity for fear of endangering their relatives and friends who are still in the territory of Ukraine temporarily occupied by the Russian Federation.

The context around Kreminna at the time of the town’s occupation

Kreminna is the administrative center of the Kreminna urban community in the Sievierodonetsk district, Luhansk region. It is located above the Krasna River near the Siverskyi Donets River. Due to its significant recreational resources (forests, lakes, rivers, children’s camps), it is known as the “lungs of Donbas.” From the military standpoint, the town is of strategic importance, as it is located on the route to Kramatorsk, the temporary regional center of the Donetsk region, which is one-hour drive away.

The shortest way from Kreminna to Kramatorsk by car takes just over an hour. Screenshot from Google maps

In 2014, when Russia’s war against Ukraine began, Kreminna was in danger of ending up in the center of the hostilities. From April to mid-July 2014, the town was on the front line. However, there were no battles in Kreminna itself.

Since the onset of the full-scale Russian invasion, which began on February 24, 2022, Kreminna has become an important target of the occupation forces. In this part of the front, the Armed Forces of Ukraine held back the enemy for a month and a half. On April 18, 2022, Serhii Haidai, the head of the Luhansk regional military-civilian administration, said that the Russian military entered Kreminna and the Ukrainian army left the town. The evacuation of civilians scheduled for April 18 was canceled. According to Oleksandr Dunets, head of the Kreminna military administration, the AFRF used up to 43 units of various equipment and armored vehicles during the offensive.

The capture of Kreminna was preceded by a massive artillery shelling of the town by the AFRF that damaged the Olimp sports center where Olympic and Paralympic athletes trained, and a fire broke out downtown on an area of more than 2 thousand square meters.

A month earlier, on March 11, 2022, Russian troops shot at a retirement home in Kreminna from a tank at close range, killing 56 people, and another 15 people were kidnapped by the AFRF.

The population was evacuated from Kreminna to the Ukraine-controlled territory by local authorities, volunteers and by local residents’ own transport. It was possible to evacuate only in the direction of Lyman, Donetsk region, along the road where Oleksandr Drobot’s car was shot on April 18, 2022.

According to Nataliia Makohon, deputy head of the Kreminna military-civilian administration, about 18,000 people left the town at that time.

Kreminna became the first town captured by the AFRF as a result of the second phase of the so-called “special military operation” announced by the Russian authorities. “This operation will continue, the next phase of this special operation is now starting. And, in my opinion, now will be an important moment during this special operation,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said in an interview with India Today on April 19. The day before, in the evening of April 18, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy confirmed in his address to Ukrainians that Russia had begun the battle for Donbas, concentrating a significant part of the troops for an offensive in eastern Ukraine. On the same day, Oleksii Danilov, Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, noted that as a result of the launched offensive, Russia aims to completely capture Donetsk and Luhansk regions by Easter, that is, by April 24, 2022.

The place where Oleksandr Drobot’s car was shelled

Oleksandr Drobot claims that his car was shelled when it crossed the administrative border of Luhansk and Donetsk regions: “It is about three kilometers from the administrative border in the direction of Lyman. There, a high-voltage line crosses the road. After the high-voltage line, there is a descent and a turn into the field; there is the road where these ruscists were standing. Everything happened in this area.”

Based on this information, MIHR established the approximate boundaries of the area that, according to the description, most closely matches the area where Drobot’s car was shelled. Google map was used for this purpose.

The screenshot shows:

- administrative border dividing Luhansk and Donetsk regions;

- the direction in which Drobot’s car was moving;

- power lines crossing the road;

- Location 1, where there is a turn into a field from the main road on which the car was moving;

- Location 2, where there is a turn into a field from the main road on which the car was moving.

The distance from the starting point, which is marked with the arrow on the map, to Location 2 is 4 km, to Location 1—3 km. This is the approximate distance mentioned by Oleksandr Drobot. Accordingly, the shelling of the car took place within the area marked with numbers 1 and 2.

Who shelled it and from where

While studying the circumstances of the shelling of Drobot’s car, the MIHR team faced the difficult task of finding out who exactly fired the first shot, since on April 18, the day it happened, the AFU left Kreminna in the direction of Lyman. And that is where Drobot and his family were heading through the villages of Torske and Zarichne.

There is a moment in his testimony when he says that the first shot was fired from the front, and then the car was shot from behind. Under such circumstances, MIHR put forward a hypothesis that Drobot’s car could have been caught in the crossfire of the AFU and the AFRF. Here is how the victim himself describes the beginning of the shelling:

“They were shooting somewhere in front. I could not see them. We were in the crossfire—those from behind were shooting, and others were shooting from the front. Those in front were far away, I did not see them at all.”

When asked by MIHR whether he could have been caught in the crossfire of the Russian and Ukrainian armies, Drobot answers emphatically: “No, no, no, it was only the Russians.”

At the same time, the military’s operational data testify to the extreme intensity and dynamism of fighting in the area during the third decade of April. According to Brigadier General Dmytro Krasylnikov, commander of the operational-tactical group “North,” the Russians used the forces of almost the entire Central Military District of the AFRF to capture Kreminna and that direction in general. “The 90th tank division entered Kreminna,” Krasylnikov says. “The day before they fired from at least 40 tanks at two strongholds of the 79th Brigade of the AFU on the outskirts of Kreminna. Then the forces of the 21st and 30th motorized rifle brigades continued to advance to Lyman through Zarichne and Torske. They approached Zarichne from two sides. The 15th brigade was advancing along the Oskil river. And they had 74th and 35th brigades in reserve; supposedly, they were to come up later.”

In the context of the shelling of Drobot’s car, the General’s words that the AFRF were advancing on Zarichne (the village that passes into Torske) from two sides are important. This indicates that the first shot at Drobot’s car could have been made by the AFRF, which were advancing from the flanks, trying to surround the AFU.

At the same time, the AFU General Staff’s report that Russian troops occupied the village of Zarichne appeared only in the morning of April 27, 2022. That is, from April 18 to April 27, the village was in the gray zone.

It should be noted that the AFU troops who left Kreminna were already in Lyman, Donetsk region, 10 km west of Zarichne, in the afternoon of April 18. This was reported to MIHR by Oleksandr Ungurian, a resident of Lyman, who spoke to the AFU military that day. “On April 18, I stopped at a service station near the bakery, our military were there next to an old beaten up Zhiguli. They said they had left Kreminna less than an hour before. And it was about 12 noon when we talked. They said they were holding some kind of checkpoint there. They only had an APC as a cover. That’s all,” Ungurian says. “And more than 10 tanks attacked them; artillery shelling began, infantry was coming, tanks were leveling everything to the ground. And it was not just one place; they were advancing in a line. While we were at the service station, we could hear a column of our vehicles moving towards Kreminna as reinforcement. So the military told me: “If we had waited for them, we would not have been alive to talk to you now.”

Timing is important in these testimonies. The road from Kreminna to Lyman, the straight that Drobot took, takes about 40 minutes by car. That is, the soldiers with whom Ungurian talked left the place no later than 11 o’clock on April 18. However, they could have left much earlier. The only question is whether they were driving on the same road as Drobot. We will find out later that they did not, because this road was completely shelled by the Russians.

To understand who controlled the territory in the area of Torske, Zarichne and other nearby villages on April 18, let’s turn to the testimony of Oleksandr Drobot, who, after the shelling, reached the first house he came across (the first village there is Torske). “I called my acquaintances. They found their acquaintance. He came, picked me up, changed my clothes, washed me. And we went to another village. And then the Russians came; they set up a checkpoint at the entrance. I was on the porch when Russian special forces were coming in masks and glasses. They asked through the fence: “Are you alone?” “Yes, I am” (I hid my wounded leg behind the jamb). “Did they check your documents?” “Yes, they did.” And they just went on. They did not come into the yard. God led them away.”

Drobot didn’t say in which village he was hiding with his acquaintances in order not to put them in danger. However, twice during the interview he noted that they “went to another village.” But they did not. There are several villages around Torske within walking distance. There are Yampolivka, Terny (already occupied at the time) to the north, Zarichne to the west, separated from Torske only by the narrow river Zherebets, and Yampil to the south.

Since Drobot said that Russians had already visited the village where he was brought, this means that at that time the occupation of this area by the AFRF de facto continued, yet the General Staff of the AFU would report about the capture of Zarichne only on April 27.

Moreover, analyzing the operational situation around Yampolivka, 1.5 km from Torske, MIHR found a testimony of border guard Pavlo Zharykov, who said in an interview with the Glavkom publication that on April 15, 2022, he was wounded near Yampolivka when Russian troops were 1.5 km from the positions of the Ukrainian military. The date of April 15 (i.e., three days before the capture of Kreminna by Russian troops) and the distance of 1.5 km indicate a very close fire contact of the enemy in this area, where Drobot was going with his wife and mother-in-law on April 18. That is, Russian military were already in the north of the road that runs from Kreminna to Lyman through Torske and Zarichne on April 15 (three days before their trip). It is likely that they organized an ambush here to strike Ukrainian units that had to retreat from Kreminna.

In order to find out the circumstances of AFU’s retreat from Kreminna, MIHR met with a serviceman who organized the withdrawal of Ukrainian soldiers from the town on April 17-18, 2022. His call sign is Cossack.

“On April 17, along this route (where Drobot’s car was shelled. —MIHR) I was still pulling out the killed and wounded from Kreminna. I drove at 100-120 km/h and slipped through, but the road was already shot through by that time,” says Cossack. “We were developing other exit routes because it was clear that no one would let us out there. When we began to withdraw, our intelligence reported that they lined up tanks, crossed the road, stood in a wedge and waited for us to go out along this road to shoot us directly, as in a shooting range, like in Ilovaisk. But we went through the woods, in four columns. And in fact, the entire group that was engaged in the defense of Kreminna came out without losses. I was the last one to leave with my men at 5:15 am on April 18. We were already clearly targeted by Grads. It was in the forest; there is a large power station there, and it was the only free road that ran parallel to the power line. We started the withdrawal in the evening of April 17.”

According to the serviceman, Kreminna was attacked from three sides: Zhytlovka, Rubizhne and Torske, which was already under Russian occupation on April 18. The Russian military entered Torske from the north from the village of Terny through Yampolivka, where the Russians concentrated a huge strike group on April 17.

“The fighting for Terny lasted a month, the enemy formed a very large strike group in that direction, which began to push through our defense on April 17,” says Cossack. “There were two checkpoints on the stretch from Kreminna to Lyman, both in Torske. But the Russians were there on the same day, that is, April 18; they closed the encirclement around Kreminna from three sides. A civilian car could not get to the battlefield, because the battlefield was no longer there. On April 18, we were already very far away.”

The first screen shows the direction and approximate route of the AFU’s retreat from Kreminna towards Lyman. The power line behind which Drobot’s car was shelled is also marked. The AFRF offensive is marked from the north, from the Torske village in the direction of Kreminna.

The same power plant that the AFU passed during their retreat is in that square.

This, based on the totality of the evidence collected and analyzed, MIHR concluded that the first shot at Oleksandr Drobot’s car was almost certainly fired by Russian troops, who at that time were moving towards Kreminna from the direction of Torske, and Drobot was heading towards them.

At the same time, the question remains, which military unit shot the car from behind, that is, from the Kreminna side. Here is what the victim says: “My wife said to me: ‘Look, the military are there.’ And they were lined up in a wedge, with a tank on each side. On the tower of one of the tanks, my wife saw a painted circle with a square inside it. Well, we couldn’t go back because we were going down the hill, so we went forward.”

It should be noted that most of the equipment used by Russia in the war against Ukraine is marked with the symbols shown in Fig. Remember these symbols.

Key symbols on the Russian army equipment used in the war against Ukraine

At this point, we cannot confirm that the interpretations of the symbols are still relevant because this figure was created at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but it demonstrates the basic markings that have not changed.

As we can see, there is no circle with a square inside it. Moreover, regarding this particular marking, MIHR talked with servicemen of several motorized infantry and rifle units, Ukrainian aerial reconnaissance, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense, as well as those who held the defense of Kreminna. All of them assure that they have never seen the sign Drobot said his wife mentioned on Russian equipment.

This suggests that the woman could be mistaken. At least regarding the details. However, it should be noted that in addition to basic markings, each of the AFRF units has special tactical markings on its equipment.

For example, General Krasylnykov notes that the 90th tank division entered Kreminna, and the 21st and 30th motorized rifle brigades continued their advance to Lyman through Zarichne and Torske. Specialized websites provide images of tactical insignia used by these units of the AFRF. In particular, the 21st motorized rifle brigade has a circle with a rhombus inside it. Perhaps this is what Drobot’s wife saw.

The insignia of a circle with a rhombus inside it is used by the 21st separate motorized rifle brigade of the AFRF, which attacked Lyman through Torske. It is likely that this is exactly what Oleksandr Drobot’s wife saw.

Meanwhile, we analyzed photos from the occupied Kreminna, which show Russian soldiers and their equipment. All of it is marked with a circle. Given that this geometric figure is difficult to confuse with the familiar Z, V, A or X, we are of the opinion that Drobot’s wife saw a circle, and was mistaken about the square inside. Drobot himself also says that he saw a circle.

Military equipment of the Russian occupation forces in the area of Kreminna, photo by Ivan Ivannikov. The identification insignia is a white circle, including on the chevron of a serviceman.

In addition to General Krasylnykov, the fighter with the Cossack call sign who held the defense of the town, speaks about the units that entered Kreminna. According to him, active fighting for the town began three days before the AFU withdrew from Kreminna. And the Kadyrovites were the first to come there.

“We had a contact battle with them,” Cossack recalls. “Some of them were killed, we passed their documents on as appropriate. So they were 100% Kadyrovites, we know that. We also took prisoners and interrogated them. And the 1st army corps of the so-called LPR also entered Kreminna.

Victims

The exact number of those killed on the road between Kreminna and Torske is not yet known. On April 18, 2022 the head of the Luhansk regional MCA Serhii Haidai reported four dead and one wounded.

These data coincide with those provided by Oleksandr Drobot. The two victims of the shelling are his wife and his mother-in-law. He saw two more bodies on the road when he was walking towards Torske. He himself was the wounded. “As I was walking, I saw the same Zhiguli completely burnt, still smoking. And then, one by one, the cars started to appear. I did not see people there; apparently, they all burned down,” Drobot says. “Then more and more cars. It was dark, night. I was walking with the thought that I would be killed. I saw an ambulance there. The light in the car was on, but there was no one inside. The ambulance was not burned. I walked around it and carried on. Then I saw two corpses on the road. As I went further, I saw burnt cars again. The doors were closed everywhere, so I think all the people were killed.”

At the same time, three different sources from the Ukrainian military and authorities informed MIHR that the number of victims on this road exceeds 40 people.

In particular, this was stated by Natalia Makohon, deputy head of the Kreminna military-civilian administration, citing her own sources. Since our team did not have access to the area where the shelling took place during the entire investigation, this information remains unconfirmed.

Under such circumstances, the MIHR took the path of collecting and analyzing subjective and objective data in order to work out a version according to which there could have been more victims on the road between Kreminna and Torske than the four officially confirmed by the authorities.

We started with the fact that the number of destroyed cars Drobot counted was at least 15. Many of them, he said, were smoking and the doors were closed. Given that each car had to be driven by someone, we assume that there could be at least 15 potential victims of the shelling. At the same time, during evacuation, people almost never go alone, so 15 can be safely multiplied by two, which in the end gives 30 potential victims of shelling.

However, the question arises, could people from the shelled cars escape? Of course, they could. As it happened with the ambulance crew from Lyman, which went to help the wounded Drobot and was also shelled.

Here is how the mayor of Lyman Oleksandr Zhuravlev comments on this episode: “Our ambulance went there, but came under fire. We wanted to send another one, but there was massive shelling, a police officer called us and said that we cannot send it because the sky is beginning to mix with the ground there. The paramedic and the driver of the shelled ambulance got to Lyman on foot. And the wounded doctor Usachiov, who was in charge of our EMS station in Lyman, then got to Torske, stayed there with the orcs and worked with them.”

MIHR found a video in which Mykola Usachiov gives an interview to the Donbass Decides telegram channel about how he ended up in the occupied territory.

Mykola Usachiov gives an interview to the Donbass Decides telegram channel about how he ended up in the occupied territory

It is striking that, when speaking about the shelling of the ambulance, the former head of the Lyman EMS station doesn’t say who exactly shelled it. Instead, the Donbass Decides telegram channel did it for him, accompanying the interview with a summary that says: “In Krasnolymansky district, the AFU shot an ambulance when it was on its way to a wounded villager.”

We also found a photo probably showing the same ambulance from Lyman that was shot on April 18. On July 3, 2022, the photo was published on his Telegram channel by Ivan Ivannikov, a Russian correspondent of the Zvezda TV channel, who, accompanied by the occupation forces, visited Kreminna and the territory around it. The photo shows that the car has damage typical of shelling but is not burned, that is, just Oleksandr Drobot described.

The shelled ambulance near the Kreminna-Lyman road

In the center—journalist Ivan Ivannikov near Kreminna, accompanied by Russian soldiers. To his left in a balaclava—Captain Fedir Panov, commander of the OGBrSnP special task force, call signs Student and Therapist, killed on July 21, 2022 during the war against Ukraine. Bottom left—photo of Panov without a balaclava.

In the center—journalist Ivan Ivannikov near Kreminna, accompanied by Russian soldiers. To his left in a balaclava—Captain Fedir Panov, commander of the OGBrSnP special task force, call signs Student and Therapist, killed on July 21, 2022 during the war against Ukraine. Bottom left—photo of Panov without a balaclava.

Analyzing Drobot’s information about 15 destroyed cars that he saw on the road to Torske, MIHR decided to find out when exactly these cars were shelled—before April 18 or earlier—because such a number of destroyed vehicles would be hard to miss for those who regularly drove there. The answer to this question will allow us to talk more about the number of people killed on this road during the evacuation from Kreminna.

We asked a serviceman with the call sign Cossack about the condition of the road. According to him, on April 17, the day before the occupation of Kreminna, he was still evacuating the dead and wounded soldiers through Torske towards Lyman. And the road, he said, was not littered with burnt cars. “There, closer to Donetsk region, there was one car thrown into a ditch,” the commander said. “It was some drunk driving and losing control three weeks before.” When asked by MIHR whether there were civilian cars destroyed or burned en masse, Cossack replied: “No, there weren’t.”

MIHR got another testimony about the shelling of civilian cars on this route by interviewing a man on the condition of anonymity, whose friends, like Drobot, left Kreminna on the morning of April 18. According to him, that day a convoy was formed in Kreminna to leave, but at the last moment most of them changed their minds. As a result, only two cars left. Unlike Drobot, they took a bypass road to the south of Kreminna through Kuzmine and Dibrova, but later on this road still connects with the main road leading from Kreminna to Lyman. According to the man, from the bypass road they drove to what remained of the Ukrainian checkpoint, where they saw a hit BRDM and bodies of Ukrainian soldiers, and further across the field was a convoy of vehicles with Russian flags, which began to shoot at them. However, the distance was considerable, so only the hood of one of the cars was hit (they later took out the bullets at a service station), and the other one slipped through at speed.

So, we have our second testimony about the morning of April 18, when Russian soldiers shelled civilian cars in the Torske area.

The bypass road most likely used by two other civilian cars shelled by the Russian military on the morning of April 18, 2022

In addition to the testimonies and photographs we have processed as part of this investigation, MIHR ordered satellite images of the road between Kreminna and Torske to be able to project the information from it onto what we have heard from witnesses. The companies that MIHR contacted do not have images of the area we need for April 18. The photo closest to this date we managed to find is dated April 26, 2022, that is, eight days after the shelling.

However, this suited our purpose because Oleksandr Drobot stated that the bodies of his wife and mother-in-law had been lying in the open air in the ditch for 17 days. Therefore, when ordering satellite images, we hoped not only to determine the place of their deaths as accurately as possible, but also to see Drobot’s destroyed car as well as other victims. However, satellite imagery is always a lottery where a lot is determined by luck, which is made up of many factors, including the angle at which the satellite took the photo, whether the area was covered by clouds, how the sun was shining, etc. In addition, satellites have limited resolution, so the cars in their images are often the size of a matchbox lying on the ground which you try to identify from the fifth floor, and it is almost impossible to recognize a person in such images.

Nevertheless, the images we received gave us a lot of crucial information about the general situation in the area of the Kreminna-Torske road. In the photo below, we can see that the surrounding area is littered with shell craters (the numerous black dots); it even captured the moment of the explosion, which we marked with a white square. This indicates an extremely powerful confrontation in this area, especially at the entrance to Torske.

The road from Kreminna towards Torske, Zarichne, Lyman. The ground is riddled with craters that are visible as black spots. You can see the moment of explosion of one of the shells, marked with a white square

At the same time, on the entire section of the Kreminna-Torske road that we studied, we found only a few objects on satellite images that can be considered vehicles. The most clearly identifiable is a white object located on the left side of the road 3 km from Torske in the direction of Kreminna—approximately at the distance where, according to Dr. Mykola Usachiov, his ambulance was shelled; in the photo below this object is marked with the number 1.

The number 1 indicates an object that looks like the shelled ambulance

On the same roadside, but a few hundred meters closer to Kreminna, we see several more light-colored objects that look like the remains of a car. It is approximately in this area that Drobot’s vehicle was shelled. An important detail for determining where the car was shelled is that when the victim was hiding in the ditch, he saw the power lines that he had passed before. Further towards Kreminna we found several other objects on the road, including in the ditch, which could be the remains of cars or even people, but the resolution of the image is not sufficient to confirm this with certainty.

Instead, at the entrance to the village of Torske, we counted at least 15 vehicles in the marked area No. 1, and 12 vehicles in area No. 2. It is impossible to judge from the photos whether these vehicles are in working condition or burnt. However, given that the photos are dated April 26, that is, eight days have passed since the shelling of Drobot’s car, and we did not see the accumulation of broken vehicles on the road itself, it is likely that they were brought to the areas marked No. 1 and No. 2. On the satellite images we also marked other objects of non-natural origin, which may be vehicles or their parts. In total, there are 20 of them, excluding those we have already mentioned. Square No. 3 marks the checkpoint at the entrance to Torske from Kreminna and the shelter trenches.

Aerial reconnaissance data could help to better see the picture in the area of Kreminna-Torske at the end of April. However, the Ukrainian military, at MIHR’s request, reported that they do not have such data on the area that interests us.

Conclusions

According to MIHR’s information, Donetsk Regional Prosecutor’s Office registered the fact of shelling of Oleksandr Drobot’s car. However, there are no proceedings on the shelling of the ambulance.

The exact number of civilian casualties during the evacuation from Kreminna on the road towards Torske, Zarichne and Lyman can be established only after conditions for access to the area become available.

At the same time, MIHR notes that the de-occupation of Lyman in the Donetsk region and the Ukrainian military’s advance to positions in the area of the road connecting Zarichne, Torske and Kreminna have been accompanied by intense fighting, which risks destroying evidence of Russian war crimes against civilians.

This report is based on the preliminary results of the investigation of war crimes committed by the Russian occupation forces on the Kreminna-Torske-Zarichne-Lyman road. MIHR will continue to collect evidence on this episode once it has access to these territories, in particular to the burial sites in Kreminna.

P.S.There are roads from Kreminna not only to Lyman, but also to Stara Krasnianka and Zhytlivka. The Media Initiative for Human Rights has testimonies and evidence indicating that, at the time when the car of Oleksandr Drobot and his family was shelled, civilian cars were also exploding on the road towards Zhytlivka, where we know about at least two victims. All these facts are being processed by MIHR.

Stanislav Miroshnychenko, MIHR journalist

Olha Reshetylova, co-founder, coordinator of the War and Justice department of MIHR