Eight Years in Captivity: Prisoners of the “Donetsk Republic” Are No Longer Being Returned to Ukraine

In mid-2017, a wave of arrests of “Ukrainian spies” and “terrorists” began in the occupied part of the Donetsk region—allegedly due to a leak of information about them by an SSU officer who sided with Russia. Numerous arrests followed throughout the rest of 2017 and all of 2018, with some additional detentions taking place in 2019.

“Since the end of 2017, people were being arrested constantly,” former prisoner Serhii Protasov, who worked as a children’s photographer in Donetsk, recalls.

— I remember two groups were detained in just one month. It was no coincidence. Those who were involved in my case as accomplices were arrested six months after me.

“When I was released, I filed a statement with the SSU, requesting to initiate a criminal case or, if such a case already existed, to inform me about the investigation. The response was that the person responsible for the leak had been identified and was in Donetsk,” Protasov comments.

Serhii Protasov was held captive from 2017 to 2022. Photo: Family archive

All the detainees were tortured—both to force confessions and purely for the amusement of sadistic investigators and detention facilities officials. On the other hand, the so-called investigators and lawyers, who were totally dependent on the occupying security, persuaded the detainees to sign confessions as soon as possible to expedite the trial and prisoner exchange. The quasi-courts handed down generous sentences—starting from ten years in prison. However, few people bothered to pay attention— everyone hoped for a prompt exchange.

Before the full-scale invasion, the final significant prisoner exchange between Ukraine and the Russian puppet “Donetsk Republic” occurred in 2019 when dozens of arrested Donetsk residents were still awaiting so-called court verdicts. However, the “republic” did not hand over everyone convicted in Donetsk.

“There were many people on the exchange lists, some of whom were arrested before me,” Andrii Kochmuradov, an IT specialist from Donetsk, recalls. He was arrested along with his wife, Olena Lazareva. Both were sentenced to 15 years in prison and exchanged in 2019.

“When I ended up in ‘Izoliatsiia,’ some people had already been there for several months. Then we had the ‘trial,’ during which about 30 people were sentenced in one day. We were all supposed to be part of the exchange. However, I don’t know why I was exchanged while the others were not.”

Andrii Kochmuradov and Olena Lazareva remained behind bars in the Russian puppet “DPR” from 2017 to 2019. Photo: Spektr.Press

Since 2020, prisoner exchanges with the “republic” essentially ceased— first, under the pretext of the COVID-19 pandemic and later due to the full-scale Russian invasion. After Russia annexed parts of the eastern regions it had controlled since 2014, on September 30, 2022, Kyiv began negotiating prisoner exchanges directly with Moscow.

Not only Donetsk, Luhansk, and Crimea, but also Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and numerous Russian prisons have been filled by the occupiers, no longer with dozens, but with thousands of new Ukrainian captives.

Lost in this sea of misery are two islands in the Donetsk region— men’s and women’s colonies—holding several dozen people waiting for a “swift” exchange for seven years. Most of them have lost their health, families, elderly parents—and hope.

Since 2020, Ukraine has managed to free only four civilians who were captured before the full-scale invasion—one man and three women.

“Some guys are already on the verge. There are guys whose wives left them. In five years, I was the only one who made it out. You should have seen their eyes when I was leaving—how they looked at me! I know that when I walked out, they were desperate,” Valerii Matiushenko recalls. He spent seven years in a colony for political prisoners in occupied Makiivka.

Valerii Matiushenko after returning to Ukraine. He was held captive from 2017 to 2024. Photo: Ukrainian Ombudsperson

The Day That Never Came

Based on estimates by former prisoners interviewed by the MIHR, around 50 political prisoners remain in Donetsk’s colonies, having been imprisoned before 2022. For various reasons, not all of them are included in the lists of captives. There is no information about the fate of several prisoners.

For a long time, several dozen more people arrested on political charges were held in pretrial detention facilities in Donetsk and Makiivka without a “trial.” After Russia’s annexation, when Russian security forces were assigned to the occupied part of the Donetsk region to implement Russian criminal and procedural legislation, the cases of those imprisoned by the “republic” began to be reviewed. As a result, some detainees were released from pretrial detention. Thus, at the end of 2022, Serhii Protasov, arrested in 2017, was set free.

“They changed my charge from ‘aiding terrorism’ to ‘participation in a terrorist organization,’ then back to ‘aiding terrorism.’ On the day I was released, the charge was changed again—from ‘aiding terrorism’ to ‘failure to report a crime.’ The penalty under this Article is a fine or up to one year in prison,” Protasov explained to the MIHR.

Among others, in 2023, Olha Mozolevska and Ihor Mikheiev, detained in 2017 as suspects in the attempted abduction of one of the militant commanders and “pleaded guilty” during interrogations, were released: the new investigator found no evidence to support their guilt.

Olha Mozolevska was held in Russian captivity from 2017 to 2023. After her release, her whereabouts remain unknown. Photo: Family archive

However, the “early” release of a prisoner in Donetsk is not the same as being handed over to Ukraine in a prisoner exchange. While Mikheiev was freed and managed to leave the occupied territory, Mozolevska disappeared. Many former prisoners believe she was abducted again and thrown back behind bars.

There were four other defendants involved in the case of the attempted abduction of one of the militant commanders: Stanislav Boranov from Sumy, Oleksandr Tytarenko from Luhansk, Volodymyr Cherkas from Donetsk, and another man, unknown to former prisoners and their relatives, who was allegedly murdered during his detention. The Cherkas, Boranov, and Titarenko cases were re-investigated in 2023, and all three were later “tried” in Donetsk.

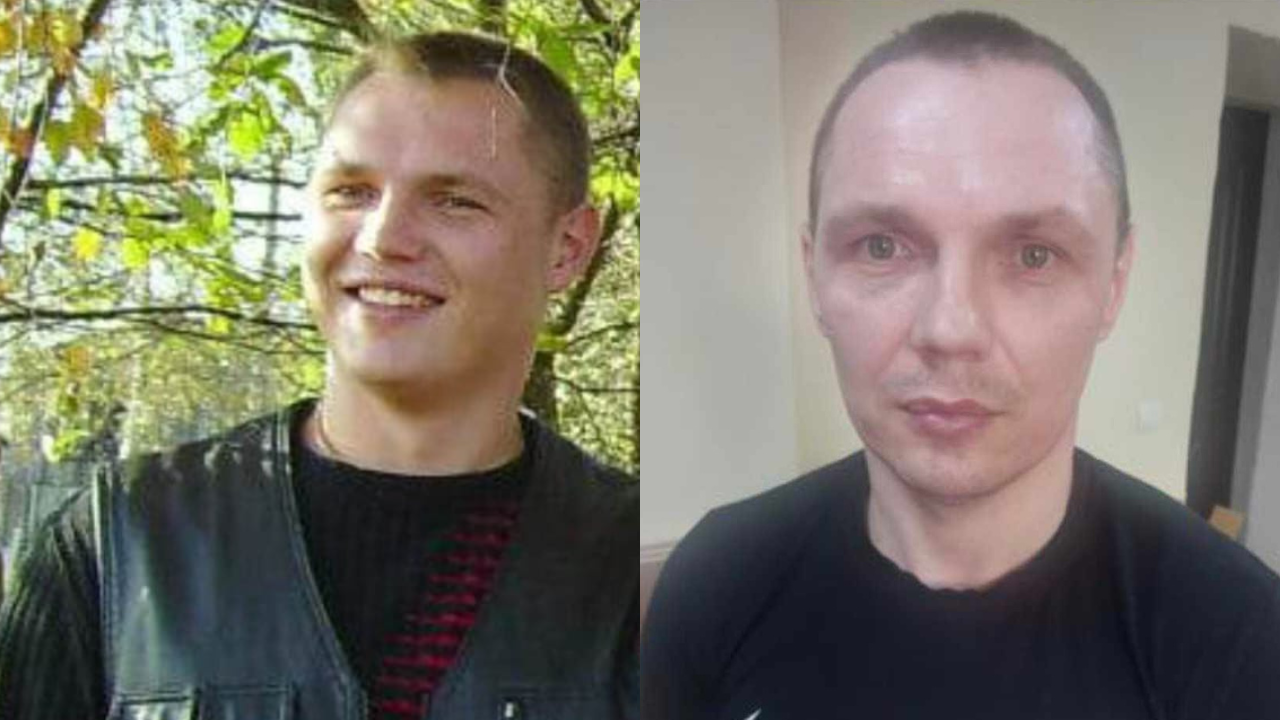

At the end of December 2023, Valentyna Boranova, Stanislav’s mother, received a letter from her son in which he hoped to return home the following year.

Stanislav Boranov before his detention (left) and during his time in prison (right). Photo: Family archive

The last court hearing in this case was held in May 2024. Relatives already knew that the three men would be released. Maryna Shifer, Volodymyr Cherkas’s daughter, arrived in Ukraine from Germany, where she collects humanitarian and military aid for Ukrainians. She was hoping to finally hug her father.

“I was planning how to get my dad out of Donetsk, imagining the day when I would see him,” she shares in an interview with MIHR.

Stanislav’s friends—former prisoners—were waiting for him outside the courthouse. Valentyna Boranova was asked to wait for a call from her son. Maryna Shifer hoped her father’s lawyer and public defender would contact her. Boranova received a call late that evening; Maryna was contacted the next day.

It turned out that the moment when the recently released Tytarenko, Cherkas, and Boranov exited the courthouse, they were immediately surrounded by people in balaclavas—presumably from the FSB—who placed them into a vehicle and drove away. Since then, the fate of all three men remains unknown. Under unconfirmed reports, they are being held in a pretrial detention center in either Rostov or Belgorod regions.

Volodymyr Cherkas went missing in Donetsk in the fall of 2017. His whereabouts remain unknown. Photo: Family archive

Serhii Protasov, who couldn’t leave Donetsk for a year after his release due to his expired Ukrainian passport, also lived fearing repeated arrest.

“By some miracle, I got lucky that I was released and managed to leave,” he recounts. “I wouldn’t have been surprised if I ended up somewhere with Vova and Stas. I’m not the ace in the deck, but they hold me for six years, too.”

Valentyna Boranova notes that after Stanislav’s abduction, she lost contact with his friends who had been waiting for him outside the courthouse that day. Maryna Shifer no longer has contact with her father’s lawyer and public defender.

You Have to Suffer

In addition to physical torture, numerous psychological abuses have been and continue to be used against political prisoners in pretrial detention facilities and colonies in the occupied part of Ukraine. One of the cruelest is cutting off any means of contacting relatives.

“For me, understanding what was happening to my mom while I was behind bars was much harder than being there myself. It was more painful when I saw my emaciated mother than when I was, for example, beaten. I still can’t forgive the fact that I was never allowed to tell my parents that I was okay, so they wouldn’t worry at least a little, because it cost them a lot in terms of their mental and physical health,” Maryna Yurchak, released from captivity in 2024, shares in an interview with the MIHR. After her abduction in Donetsk, the “investigators” refused to let her make a call to her parents, claiming she “didn’t deserve it.”

Maryna Yurchak remained in captivity from 2017 to 2024. Photo: family archive

Some families of the prisoners learned about the fate and whereabouts of their relatives weeks and even years after their abduction, and not from the prisoners themselves or the Donetsk “authorities,” but from other prisoners who had been released.

This was the case with the families of Volodymyr Cherkas, Stanislav Boranov, and Oleksandr Tytarenko, abducted in Donetsk in November 2017. It was only after the large-scale prisoner exchange in 2019 that it became known that they were alive but still in captivity. While their relatives were searching for Stanislav Boranov and Oleksandr Tytarenko through Ukrainian state authorities, they were held in Donetsk under the names Bozhko and Teploukhov—they probably entered the occupied territory with forged documents.

Some relatives had to travel to Donetsk to get information, pounding the doorsteps of the ‘Ministry of State Security’ where they were lied to about the lack of information before the abduction was eventually acknowledged. This was the case, for example, with Halyna Dzytsiuk, whose son Viktor was abducted in 2017 at a checkpoint on the outskirts of Donetsk and nearly tortured to death while his mother tried to find him.

Viktor Dzytsiuk has been held in Russian captivity since 2017. Photo: Family archive

Some relatives learned about the “trials” and “verdicts” from local news, like 80-year-old Albina Holovko, the grandmother of IT specialist Dmytro Skoryk, who was abducted from a hospital in Donetsk with pneumonia in 2019. Holovko found out about the whereabouts of her only grandson, whom she had raised herself after his parents passed away, in the same way—thanks to a former prisoner who contacted her after being released.

Dmytro Skoryk has been in captivity since 2019. Photo: Family archive

You will find little new information in accounts of current Ukrainian prisoners of Russia if you have read stories about the Stalinist GULAG. The Russian Federation has a long history and well-developed methods of breaking the body and spirit of political opponents, tested on millions. Essentially, these methods boil down to two goals: to isolate and humiliate.

Many of the relatives who used to visit their children, parents, partners, brothers, or sisters in captivity in the occupied territories can no longer do so since the Russians first closed checkpoints due to COVID-19, then turned the entire Russia-Ukraine border into a frontline, and, finally, effectively blocked Ukrainian citizens from entering.

There is no direct telephone connection to Ukraine in the Russian-occupied part of Ukraine. Some prisoners have access to Russian ZT (Zona Telecom), or they somehow manage to get mobile phones from local mobile operators.

Some relatives can get in touch occasionally through local intermediaries who can receive calls through Zona Telecom.

“The connection is tapped, and there is little you can ask, but at least there is a chance to hear that he’s alive,” Regina Kolesnikova, a colleague of doctor and businessman Ihor Kirianenko from Donetsk, recounts. He was maimed and severely ill after enduring torture.

Ihor Kirianenko was detained on December 30, 2018. He still remains in captivity. Photo: family archive

Letters are occasionally exchanged in the same way. Relatives also rely on some local residents to send packages. Usually, a person or their relatives on the free territory would transfer the cost of goods the prisoner needs.

The largest allowed parcel size currently is 20 kilograms per person every three months. Neither the Ukrainian government nor international humanitarian organizations facilitate the delivery of packages. For those with no one to care for them, relatives of other prisoners gather parcels. For example, this is how they are trying to help neurologist Yurii Shapovalov, whose 82-year-old mother, who was the only one visiting him in prison, recently passed away.

Yurii Shapovalov disappeared in Donetsk on January 11, 2018. He remains in Russian captivity to this day. Photo: family archive

At the same time, not all families of Ukrainian captives have intermediaries in the occupied territories. Almost every family has a story of a local contact—sometimes another former prisoner or a close relative of one of the detainees—suddenly disappearing. It’s hard to survive behind bars without parcels; for some, it’s impossible. The prison food is poor, and the infirmary lacks medicines. If you are held among criminals, how you’re treated often depends on what and how much you receive from home.

Placing political prisoners among those convicted of criminal offenses is a sadistic practice reminiscent of the GULAG era. The consequences range from discomfort due to living among people with vastly different values and interests to grave danger, especially considering that among the criminals in Donetsk prisons, there are many former combatants.

Serhii Protasov recalls that the administration of the detention facility where he was held for six years tried to place as many “diverse” prisoners in each cell as possible to prevent them from bonding with one another.

“When they discovered that everyone in a cell got along and lived peacefully, they would make rearrangements, throwing in a “cheerful” person into the cell to stir up emotions and activity,” Protasov jokes in an interview with the MIHR. “Apparently, people can be such scumbags…”

“Everything is done to make life unbearable. You’re not supposed to laugh because you’re supposed to suffer. If you laugh, it means you’re doing well, and they need to ensure it’s not so funny,” Valerii Matiushenko explains.

Another form of physical and psychological torture is the denial of medical care. This is a systemic issue in all places of detention. Matiushenko recalls how he once felt very ill. However, the colony administration only agreed to call an ambulance several days later—when he could no longer endure the pain.

“When they put handcuffs and shackles on you, they treat you like a criminal. In the hospital in Makiivka, a surgeon came up and claimed, ‘No one is going to do anything because of COVID.’ They returned me to the car and drove me back,” Matiushenko recalls.

Surviving in such conditions is possible for Ukrainian political prisoners only thanks to the support of their families, friends, and mutual support. On Matiushenko’s account, prisoners often sought help from Yurii Shapovalov and surgeon Ihor Nazarenko, who have also been imprisoned for over seven years. “If it weren’t for Ihor Nazarenko, it would have been hard for me,” Matiushenko shares. “Anyone who had problems addressed Nazarenko.”

Ihor Nazarenko has been held in captivity since November 2017. Photo: family archive

Like a Horse in a Mine

Stanislav Boranov has a 12-year-old son. Each time a prisoner is exchanged with Russia, he asks why his father has not returned home.

Valerii Matiushenko notes that each exchange adds to the suffering of those waiting for seven years to be released: “For example, when 32 people were exchanged in 2019, and 11 of us were left behind, I was shocked. We scattered to different corners for a week or two and didn’t talk to each other.”

Former prisoners believe that the places on the exchange lists are a subject of dispute and bargaining on both sides; the Russian side deliberately excludes some individuals from the list, for example, as an act of revenge.

“I was handled by the same investigator for about two years, but about four months before the exchange, my case was transferred to another one,” Serhii Protasov recalls. “After the exchange, that investigator was dismissed, and my case was returned to my original one. When he saw me again, he asked in surprise, ‘What are you doing here? You were on the exchange list.’ That second investigator must have been selling places on the lists.”

“I was prepared to serve ten years,” Matiushenko comments. “Before I was transferred out of ‘Izoliatsiia,’ one of ‘my’ two operatives—a former SSU officer—came to see me suggesting, ‘Sign a paper agreeing to cooperate.’ I refused, and when he was leaving, he declared, ‘You will serve all ten years.’’’

At the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, where the relatives of captives constantly turn for information, families receive nearly the same response each time: “The Coordination Headquarters has not received any information from the International Committee of the Red Cross or from the Russian Federation regarding the captivity, health condition, or location of the specified individual.” Even though most families possess at least official documents from the colony confirming that their relative is being held there and has been sentenced under specific charges. These documents are issued to them annually.

Families believe that the Ukrainian side is not persistent enough, as there seems to be no urgency regarding the release of the “old” captives. Valentyna Boranova mentions that during one phone conversation with the SSU officer, people like her son were called “used material.”

Valerii Matiushenko notes that in the seven months since his release, he has not met any responsible high-ranking officials, even though he attempted to initiate such a meeting.

“No one cares about what is happening to the people there,” he notes. “Whether they have food, medicine, warm clothes, or medical care. I want to help. I feel guilty towards the guys. But all I can do is to send emails to their parents and wives in Donetsk saying that someone once again mentioned an exchange.”

“In the first, second, and third year, I had expectations,” Regina Kolesnikova adds. “But now you are like a horse in a mine: you keep going and understand that you can’t give up, that you have to keep moving forward, and forward, and forward. There are no more hopes; you have already burned out. I wish this all at last ended.”

On January 8, the MIHR sent a request to the SSU, asking, in particular, to explain why people who have been in captivity since before the full-scale Russian invasion are not being exchanged. As of the day of this publication, we have not received a response.

Author: Yuliia Abibok, journalist MIHR.