Forceful undress, polygraphs, and interrogations about Biolabs. Stories of combat medics who survived Russian captivity

At least 50 Ukrainian military medics are being held in Russian captivity. In addition, Russia holds many civilian doctors and nurses, subjecting them to beatings, interrogations, and baseless criminal charges.

During the critical days for the Ukrainian military in Mariupol, Anna Olsen, a senior combat medic of the 36th Separate Marine Brigade’s chemical-biological protection unit, dreaded captivity. “It would be better to shoot myself,” she thought to herself, listening to numerous stories about the torture of comrades who had returned from captivity even before the full-scale invasion.

Anna Olsen (second from right). Photo: Anna Olsen’s Instagram page

In early April 2022, Mariupol, a Ukrainian port city, fiercely defended itself against the Russian invasion, despite its impending fall. Anna’s unit sheltered in the bunkers of the Illich Steel and Iron Works plant, where she treated up to twenty wounded soldiers daily.

Medical supplies dwindled rapidly, and resupply was a distant hope.

“A guy from my unit was hit by Grad missiles,” the servicewoman recalls. “He had a severe thigh wound. We had no means to clean it, so we mixed alcohol with water and treated it with ceftriaxone [a powdered antibiotic] and made a tight dressing.”

Realizing the dire situation, Anna decided to survive at any cost, even if it meant captivity. This beautiful red-haired young lady longed to return to her family — her young daughter, mother, and sister — and was prepared to endure the hell of Russian imprisonment for them.

Anna Olsen. Photo: novynarnia.com

On April 12, 2022, after a failed attempt by her unit to break through a tight enemy encirclement, part of the Ukrainian marines from the Illich plant, including Anna Olsen, were captured by Russian forces. She spent the following six months in captivity.

Medics in Captivity

International humanitarian law protects medical personnel, who are not combatants. According to Article 28 of the Geneva Convention on the Improvement of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, they can only be detained to provide care for prisoners of war.

“In the Third Geneva Convention and Additional Protocol І to the Geneva Conventions, it is clearly outlined who cannot be captured as combatants,” comments Andriy Kryvtsov, chairman of the NGO Military Medics of Ukraine. “This includes military medical personnel and drivers of medical and evacuation vehicles.”

Combat medics provide assistance to the military. Illustrative photo

The norms on protection and respect for medical personnel during combat are universal rights recognized by most countries but ignored by the Russian Federation throughout the Russian-Ukrainian war since 2014.

During the defense of Mariupol from February to May 2022, many Ukrainian medics, both military and civilian, were captured. As of July 2022, according to MIHR, Russia held at least 100 military medics captured at Azovstal and the Illich plant.

Ukraine demanded the release of the medical personnel held in violation of the Geneva Conventions, but Russia did not respond.

For Andriy Kryvtsov, this issue is personal. His sister-in-law, Olena Kryvtsova, was among those captured in Mariupol. A 27-year-old lieutenant in the medical service, she was the chief physician of the hospital ward of the 555th Mariupol Military Hospital.

Olena Kryvtsova. Photo: family archive

Since Russia neither returned the medics to Ukrainian-controlled territory nor acknowledged their captivity, Kryvtsov began searching for Olena himself. He discovered she was held in a prison in Russia. Six months later, she returned from captivity. Kryvtsov continues to work on the release of medical personnel and holding Russia accountable for crimes against medics.

The NGO Military Medics of Ukraine has confirmed data on only 50 military medics, cases directly handled by the organization.

Meanwhile, the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War reports that as of June 2024, the total confirmed number of Ukrainian medics in captivity is 60. This information was obtained by the Coordination Headquarters from the International Committee of the Red Cross and other sources. The unconfirmed number of Ukrainian medical personnel in Russian captivity is not disclosed by the Coordination Headquarters. However, NGOs estimate the figure to be around 500 people. This includes medical personnel, medical transport drivers, and others performing medical functions, including civilian medics.

An ambulance on a square in the UK. It was shot by Russians in the Kharkiv region when medics came to help civilians. Photo: United24

“One of the significant issues is that Russia does not provide official data on captives,” comments Petro Yatsenko, head of the press service of the Coordination Headquarters.

Beaten with Hands, Feet, and a Stool

From Mariupol, Anna Olsen was taken to a colony in the occupied village of Olenivka, Donetsk region, where Russians hold prisoners of war. Men and women were separated: Olsen ended up in a cell with nearly forty other women, though the room was meant for six.

In Olenivka, female prisoners were not beaten, but Anna was held there for only about a week before being transferred to a worse place.

Many former captives recall SIZO No. 2 in Taganrog as the worst detention site in Russia. A large group from the 36th Separate Marine Brigade, named after Rear Admiral Bilinsky, along with soldiers from the 56th Separate Motorized Infantry Brigade and the 109th Separate Territorial Defense Brigade, were held here.

Taganrog pre-trial detention center

Those who experienced this detention describe brutal torture, daily beatings, and a complete lack of medical care for the injured.

“I had never seen such cruel people [referring to the SIZO staff] before,” Anna Olsen confesses.

Upon arrival, the Russian guards immediately abused the prisoners.

“As soon as we arrived, they stripped us naked and began beating us,” the medic recalls. “They call this ‘reception.’ They gave us prison uniforms that were much larger than our size and moved us through various rooms. During this entire process, we had to maintain a position where our foreheads literally touched our knees.”

Olsen describes the subsequent months in SIZO as a “survival game.”

When she was captured, she had all her documents, so the Russians knew she was a medic. However, this did not change their treatment of her. Before being held in Olenivka, fighters of the so-called DPR tried to extract a confession from her, accusing her of being a sniper.

Andriy Kryvtsov believes this is because Russia, despite its military aggression and disregard for international law, tries to “save face” in front of the Western world. To do this, the Kremlin needs to show that they are capturing not medics or civilians but Ukrainian military personnel. Therefore, attempts to label even medical personnel as snipers, shooters, or assault troops can be explained by these motives.

Anna Olsen during her military service. Photo: Anna Olsen’s Instagram page

The second reason is that the Russian authorities create a narrative for their own population.

“When we started making stories about military medics, Russians commented: ‘This can’t be! We are Russia, we don’t capture doctors, they must be snipers,'” Kryvtsov recalls.

The propaganda machine was in full swing to calm the Russians and convince them that the Russian Federation was acting “correctly” and “legally.” However, Ukrainian medics in captivity, unlike, say, the detention of Ukrainian Armed Forces soldiers, did not fit into this internal Russian myth, so they tried to portray doctors as snipers or assault troops.

During numerous interrogations at the Taganrog detention center, Anna Olsen was constantly beaten.

“They beat us with hands, feet, batons, stools — anything they could get their hands on,” she shares. “During my captivity, I suffered a traumatic brain injury, kidney damage, and a broken shoulder blade.”

These injuries were diagnosed later — doctors in the detention center did not examine or provide medical assistance to the captured Ukrainians.

During the interrogations, Russian investigators demanded information from Anna about the locations of Ukrainian military forces and ammunition depots, as well as information about foreign soldiers fighting on Ukraine’s side and even about fictitious “biolaboratories” allegedly operating in the country.

Similar information was sought from Senior Lieutenant Maryna Holinko (now a major), another captured Ukrainian medic who was also held in Taganrog for five weeks.

Polygraph test

Medical officer of the 36th Separate Marine Brigade, Maryna Holinko, served in Mariupol from October 2021. With the start of the war, she was involved in evacuating the wounded in the city surrounded by Russians and provided medical assistance to Ukrainian fighters. She recalls a catastrophic shortage of antibiotics and painkillers.

“The guys had to endure the pain because we couldn’t give them anything,” she says.

Maryna Holinko. Photo: personal archive

Holinko did not consider the possibility of captivity. She thought there were only two options: either break through to Ukrainian-controlled territory or die in battle.

“So when I was captured [on April 12, 2022], it was a real shock for me,” she shares. “Now I understand that if I had thought about this option in advance, if I had visualized what would happen, it would have been easier for me to go through it.”

Like Olsen, Holinko was first held in Olenivka and then in Taganrog. Books helped her survive there, including “Man’s Search for Meaning” by Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl about life in a Nazi concentration camp and “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” by Irish writer John Boyne. In captivity, she got hold of “The Choice” by psychologist Edith Eger, who survived the Holocaust and described her experience.

“If you look at the photos of soldiers returning from Russian captivity today, there is no difference from those who survived Nazi concentration camps,” she reflects.

Ukrainian soldiers after returning from Russian captivity. Photo: Konstantin and Vlada Liberov

Maryna didn’t even try to demand her rights as a medical worker from the jailers.

“Of course, I didn’t tell them, ‘I’m a doctor, don’t touch me.’ I knew perfectly well where I was and who we were dealing with,” she shrugs.

Anna Olsen explains that any attempt to speak with the leadership of the colonies or detention centers led to more violence. Prisoners tried not to attract attention, although initially, they did insist on meeting with representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). However, the Russian investigators said that the ICRC “won’t help because they don’t work with prisoners of war.”

The ICRC is the only international organization mandated to visit places of detention for prisoners of war. Despite this, Russia hinders the organization’s work and does not allow its representatives to monitor the conditions of the Ukrainian detainees.

At some point, a false rumor spread among the Russians that Ukrainian medics were torturing Russian prisoners of war and allegedly cutting off their genitals. This incited a new wave of brutality towards the doctors in captivity.

“They claimed that our medics pulled out their soldiers’ teeth, cut off their genitals,” Olsen recalls. “They said I must know about it because I’ve been in the military since 2015. Any denial from me resulted in more beatings.”

Marina Holinko in captivity. Photo: Russian telegram channel

Maryna Holinko was even forced to take a polygraph test to determine if she had abused Russian prisoners. Despite clear results showing she was truthful, the Russian investigators remained unconvinced.

“It’s important to understand that the staff of Russian detention facilities have a distorted view of the world,” explains Andriy Kryvtsov. “They are fed such propaganda, and then they act accordingly with the prisoners.”

Return to the home

After Taganrog, Maryna Holinko was transferred to a women’s correctional colony in Valuyki, Belgorod region, where she spent the next four months. Here, she was forced to work as a seamstress, making work uniforms for farmers, which helped her stay distracted.

On September 16, 2022, Maryna was sent to Kursk. At some point, Ukrainian women from various Russian colonies began to gather there. Rumors of an exchange spread among the prisoners, but Holinko did not hold out much hope.

“It’s dangerous to believe in such things because if it doesn’t happen, you’ll be crushed by disappointment,” she explains. “Of course, I wanted to believe it very much, but I didn’t allow myself to until our plane landed in Crimea [before the exchange, the group of women was sent to Taganrog for a day and then flown to Crimea in a cargo plane].”

On October 17, 2022, a large exchange took place, in which 108 Ukrainian women returned home from Russian captivity, including military medics Anna Olsen, Maryna Holinko, and Olena Kryvtsova.

On October 17, 2022, 108 female prisoners of war, including military medics Anna Olsen, Maryna Holinko, and Olena Kryvtsova, were returned to Ukraine. Photo: Office of the President of Ukraine

In more than two years of full-scale war, at least 78 Ukrainian medics, both military and civilian, have been released from Russian captivity, reports Petro Yatsenko, spokesperson for the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, as of June 2024.

The release of military medics today happens in the same manner as the return of all other Ukrainian defenders — through Russian-Ukrainian prisoner exchanges. The main problem is the blocking of exchanges by the Russian side, the Kremlin’s unwillingness to conduct them regularly, and the delay in negotiations, Yatsenko continues.

“Regular exchanges would increase the chances of returning our medics,” he emphasizes, but quickly adds that it’s important to remember that medical personnel should not be in captivity in the first place, and Russia should release them unconditionally.”

Female soldiers during the exchange. Photo: Office of the President of Ukraine

While military medics in captivity can at least hope for prisoner exchanges, civilians do not have this option.

“Firstly, exchanging prisoners of war for civilians is not provided for by international humanitarian law, and secondly, it would encourage the Russians to take more hostages in the temporarily occupied territories to exchange for their soldiers, which would only incentivize them,” Yatsenko continues.

To prevent this, the Coordination Headquarters is looking for other formulas to free civilian doctors.

International Pressure as Leverage

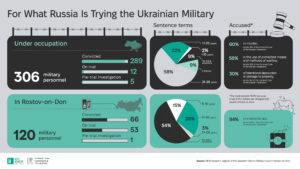

Russia not only holds Ukrainian medics captive but also carries out illegal criminal prosecutions against individuals held in colonies and detention centers in the aggressor country. Such cases should be classified as denial of the right to a fair trial, which is a war crime.

The Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War has information on eight such cases, though there may be significantly more.

However, Yatsenko assures that this will not hinder the return of these individuals in exchanges:

“This is not an obstacle because Ukraine also has convicted Russians who can be exchanged. These so-called ‘verdicts’ in Russia for captive Ukrainians are absolute fiction, which means nothing to us. Therefore, we are working on the release of such individuals as well.”

Thanks to extensive informational efforts by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, the Coordination Headquarters, and public organizations, the world is aware that Russia is holding medical personnel captive. However, to secure their release, international pressure on the aggressor country must be increased.

“It is crucial to continue pressing the Russian Federation on various platforms, including diplomatic ones, to impose additional economic sanctions against the aggressor state, and to strengthen the enforcement of these sanctions. On all possible international platforms, Russia must be consistently asked — when will Ukrainian medics be released?” says the spokesperson for the Coordination Headquarters.

At the same time, Yatsenko reminds us that the illegal detention of medical personnel is only part of a larger problem. In violation of international law, the Russians are holding not only medics but also seriously ill and wounded Ukrainians, as well as other non-combatants such as military musicians and chaplains. All these people have the right and should return to Ukrainian-controlled territory. It is crucial that the international community addresses these issues.

Andriy Kryvtsov emphasizes the need to specifically work on identifying the crimes committed by Russia in this area.

“The Prosecutor’s Office and the SBU have started to actively address the issue of military medics in captivity as war crimes,” the activist comments.

Kryvtsov believes it is time to raise such criminal cases at the international level. Several Ukrainian human rights organizations are ready to support this effort.

N.B. Article 28 of the Geneva Convention on the Improvement of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field outlines that when medics fall under the control of the opposing side, they should at least enjoy all the privileges provided by the Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949. Specifically, they should be placed in specialized prisoner of war camps, not in places of detention.

Medical personnel, like prisoners of war, cannot be subjected to moral or physical torture or any other form of coercion to obtain information from them.

The stories of Anna Olsen, Maryna Holinko, and other military and civilian medics who returned to Ukraine from Russian captivity prove that Russia ignores these provisions of international law.

Author:

Yevheniia Korolova, journalist at MIHR

Maryna Kulinich, journalist at the MIPL