Testimonies under Torture: How They Beat out Confessions of Terrorism in Taganrog

“I disagree with the court’s decision and will appeal it. I consider myself an innocent person who has been criminally prosecuted. I am a soldier who followed the orders of the state of Ukraine. I regret nothing and repent for nothing.” This is the stance Ukrainian soldier Oleksandr Maksymchuk expressed to “Mediazona,” a Russian online platform covering court proceedings in Russia after his 20-year prison sentence was announced.

Maksymchuk’s statement is perhaps the first instance of a Ukrainian prisoner of war convicted in Russia daring to publicly challenge the charges and fight for himself. Moreover, while still in custody, he has openly spoken about the torture he endured in captivity.

Spring in Mariupol

“Don’t worry about anything; everything will be fine,” 30-year-old Oleksandr Maksymchuk kept reassuring his wife, Natalia, on the eve of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The young woman was anxious but firmly refused to leave Mariupol.

“Then Sasha was called to duty. He kissed our son and me, saying he didn’t know when he would return,” his wife recalls.

The battles for Mariupol began on the very first day of the Russian invasion, and the city was quickly besieged. Natalia stayed with her two-year-old child and her sister’s family.

“We had little food left, and it was cold outside. We cooked over a fire in the yard. Then a missile hit our yard, damaging the building and killing people who were cooking on the fire,” Nataliia recounts. “My sister and I went down to the basement. We stayed there for three days. My son was crying—he was still breastfeeding, but for milk to come, I needed to drink something warm, and there was nothing warm. The people in the basement were tense, yelling at me because I couldn’t calm my baby down, saying they would calm him down themselves. It was terrifying. We were constantly afraid the Russians would come for us. My mom saved us. She came to Mariupol from the village, searching through basements. One day, she came to our door and asked if a girl with a small child was there. I screamed, ‘Mom!’ so loudly, I could hardly breathe.”

Leaving Mariupol was nearly impossible—the roads were mined, and the exits were blocked—but the women managed to flee from the city. “I immediately started looking for my husband, but there was no news about him. Later, Sasha called from someone else’s phone. He insisted that we leave the occupied territory. I didn’t want to,” the wife of the Azov soldier shares. “I kept thinking he might come back.”

Eventually, she left for Zaporizhzhia. The journey was difficult, and her greatest fear was the filtration process, especially since the occupiers had already come to their house earlier.

Captivity and “Barrack 200”

On the day of the evacuation from Azovstal, Oleksandr Maksymchuk called his wife again. He told her he was alive and that they would be taken into captivity. The soldier left the plant on May 20, departing last alongside Azov commanders.

“I thought our authorities developed a plan to bring all Mariupol defenders back from captivity. I believed it was a rescue mission because the statements were so bold. All of Ukraine believed that the Azov fighters would soon be on free territory,” Nataliia concludes.

Later, Oleksandr called from captivity. He didn’t say where he was being held. However, Nataliia quickly realized that the Azov fighters had been taken to the Volnovakha Penal Colony No. 120, better known as Olenivka. They were held in a shared barrack, but on July 27, 2022, Maksymchuk and 192 other Azov fighters were transferred to a separate hangar in the colony’s industrial premises. On the night of July 28-29, an explosion occurred in the hangar, killing over 50 prisoners. Maksymchuk suffered a severe head injury and was taken to a hospital.

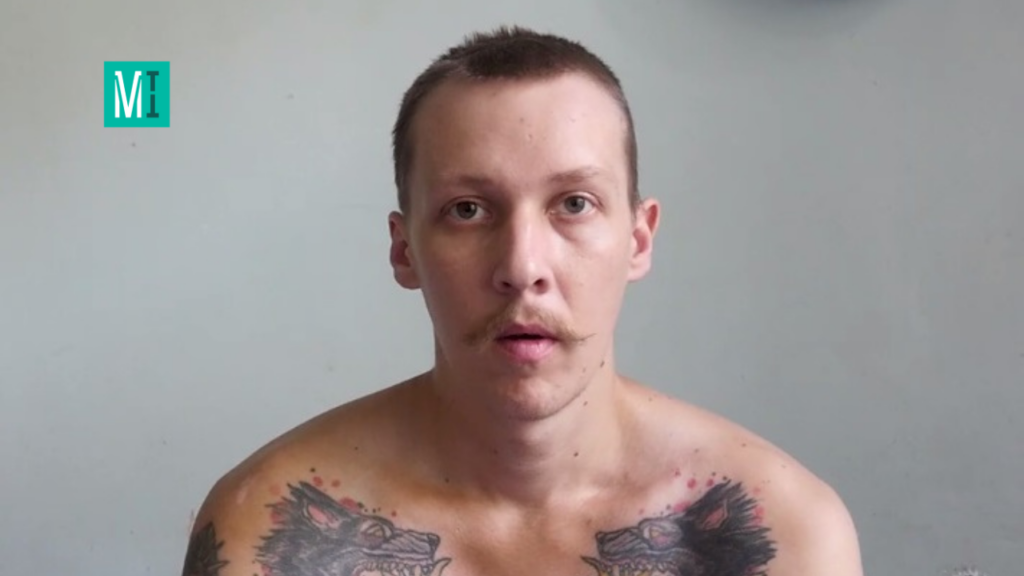

“I wake up in the morning to the news: there was an explosion in the colony, and Azov fighters were allegedly killed. Then, there was a video showing three guys. I recognized Sasha in one of them. He was lying on a bloody sheet. They asked him, ‘How’s the extraction going?’ — ‘Not great so far,’ he replied,” Oleksandr Maksymchuk’s wife recounts.

Oleksandr Maksymchuk in a Donetsk hospital after suffering severe injuries during the explosions at the Olenivka colony. Photo: Screenshot from Telegram

Nataliia was unaware of what happened next; she had no contact with her husband. Unconfirmed information suggests he was transferred to pretrial detention center No. 2 in Taganrog, Rostov Region, after the hospital.

In the spring of 2024, Oleksandr was allowed to write a letter to his family. In it, he revealed that he was being held in Detention Center No. 1 in Rostov-on-Don. Oleksandr mentioned that the investigation was ongoing and a trial was ahead. He had no intention of pleading guilty, understanding he would face a lengthy sentence. “I will stand with my head held high. They have no right to judge me,” Oleksandr’s wife quotes his words.

The trial at the Southern District Military Court began in the summer. The prosecution accused Oleksandr Maksymchuk, along with other Azov fighters, of terrorism. Only one court session was held, during which Oleksandr claimed his disagreement with the charges. He also rejected the lawyer appointed by Russia.

In October, Oleksandr was returned to Taganrog. By that time, human rights defenders were already aware that prisoners of war were being subjected to torture with particular cruelty at this location, forcing them to confess to crimes they had not committed.

Taganrog Torture Facility

On December 12, 2024, Mediazona released an audio file containing Maksymchuk’s statement. In it, he describes what is happening in Detention Center No. 2 in Taganrog:

“When I was in Taganrog, I deliberately starved myself. I remember being taught in history that ancient Roman emperors gave bread to the plebeians and arranged fights in the Colosseum to prevent riots and revolutions. This wasn’t in vain because a hungry person can do anything. So, I consciously starved in Taganrog and objected, asking to postpone the video conference to a later date. They would torture and beat me again, and I kept fasting. They applied all imaginable and unimaginable forms of pressure. I was tortured twice. They beat me and subjected me to psychological and moral pressure by applying special devices—portable electroshockers. All of this was done to force me to confess that Azov is a terrorist organization, which it is not.”

Russian journalists released these words from Maksymchuk after the verdict was announced in an open court session. However, the hearings had been closed just before — Oleksandr delivered his final statement only in front of the judge, without any extra ears or eyes. The judge allegedly decided to hold the hearings closed after Maksymchuk repeatedly reported about the torture in Detention Center No. 2 in Taganrog during his court appearances in October and November. Thus, on October 17, he complained that he had suffered a concussion from the beatings, showed the court the bruises on his forehead, and asked for an ambulance. On November 19, he provided more details: after returning from Rostov, he was tortured with electric shock, beaten with pipes, fists, and feet, his eyes were blindfolded, his hands were taped, and he was hung upside down. During the torture, he fainted several times. The prisoner was pressured to admit a fabricated crime in court, to repent, and to renounce his lawyer.

After these testimonies, the judge closed the hearing from the public.

Detention Center No. 2 in Taganrog, where Ukrainian prisoners of war are tortured. Photo: Open resources

Detention Center No. 2 in Taganrog has been a place where, since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainian defenders of Mariupol, including marines and Azov fighters, were held. All prisoners were kept incommunicado without confirmation of the place of detention and with a ban on external contacts. In these conditions, prisoners—both military and civilian—were held in inhumane conditions, beaten, and tortured. A large number of detainees later became defendants in criminal cases related to terrorism or violations of the laws and customs of war.

“This is a factory for obtaining confessions. No one cares who you are or what you did; they’ll write everything for you. And in the end, you’ll either be a war criminal or a terrorist, but certainly not a prisoner of war,” Serhii, a former prisoner of war, whose last name we are not disclosing for safety reasons, shares with MIHR.

He notes that throughout 2022–2023, he was both a witness and a victim of torture:

“Every day, people were taken from each cell to the first floor. My turn came, too. They brought me into some room. They declared: “You’ve already been handed over; we know everything, so tell us.” Then, they started beating me.”

— “You seem reluctant to speak,” they shouted. But I had nothing to say. They took me to the torture room. It’s a special room, maybe more than one, next to the investigators’ offices. They threw me on the floor, held me down, and shocked me with an electroshock device. I was lying on the floor, being beaten and yelled at:

—Tell us!

—What?!

—Crimes.

—But I’ve already told you everything!

— “Tell us again,” they ordered and continued beating me. I started carefully making things up to avoid getting tangled in the details. They began to beat me less. Then they threw me back into the cell.

After a while, the guards and FSIN officers arrived. They took Oleksandr out of the cell again and beat him with a baton:

— Do you remember what you said? Have you forgotten anything? Want us to remind you?

— No, I haven’t forgotten anything.

— You’ll say you shot at a tank with an assault rifle and killed a civilian.

— Alright.

The man was taken to an office on the first floor. There was an investigator from Rostov there.

“I had already seen his face before. He gave me a chocolate bar and a cigarette and said, ‘Alright, relax. No one will bother you anymore. Tell me what happened.’ I told my version that I supposedly killed a civilian. I signed papers, though I don’t know what they were, as the top of the documents with the investigation data was covered with a hand. Everyone gives the ‘necessary confessions’ there,” the witness explains. “They find approaches to everyone.”

Serhii was exchanged in the spring of 2023. He is convinced that if not for the exchange, he would have ended up on trial, like dozens of his comrades.

Trials of Azov Fighters

Back on August 2, 2022, the Supreme Court of Russia declared the Azov Regiment a terrorist organization and banned its activities within the country. After the battles for Mariupol and the mass surrender of Azov fighters who defended the city, Russia has zealously been crafting a distorted image of Azov as “neo-Nazis.” Russian media quote the judge who read the ruling on designating Azov as a terrorist organization, “The decision shall be executed immediately, without waiting for its enactment.”

The MIHR is aware that since the spring of 2024, judges in one of the courts in Rostov began imposing preventive measures of detention for Azov fighters held incommunicado in the Taganrog detention center No. 2. This applied to several dozen Azov soldiers. After two years of captivity and torture, the Russian system officially began treating them as extraordinarily hazardous military personnel who must remain behind bars. Following this, they were transferred to detention facilities in Rostov, initially to detention center No. 1 and later to No. 5. The next step would be court trials. By the end of spring and into the summer of 2024, several dozen similar cases of terrorism involving Azov fighters emerged.

Thus, the Russian prosecution changed its approach: in the summer of 2022, it announced a single large trial against Azov fighters, but it failed — instead of combat soldiers, cooks, former drivers, and the brigade’s dog handler ended up in the dock. Now, however, there are many separate trials. And in each of them, the accused usually pleads guilty.

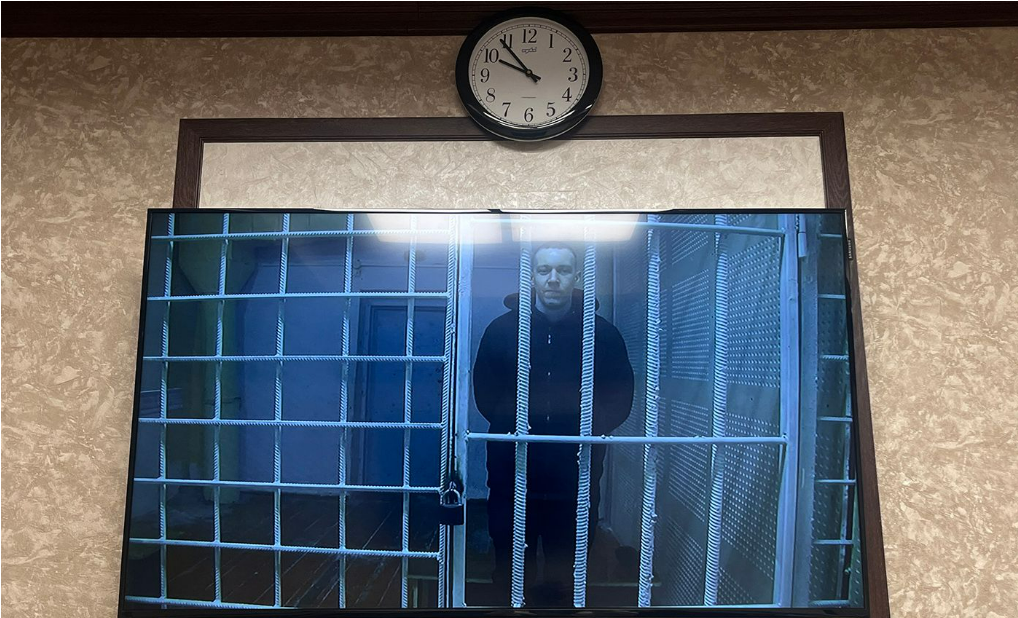

Prisoner of war Oleksandr Maksymchuk participates online in a court hearing in Russia. Photo: Mediazona

Under Russian law, a defendant can choose one of three trial procedures: a special procedure, a trial by a single judge, or a trial by a panel of three judges. The special procedure offered by the prosecutor’s office to Ukrainian prisoners of war involves the defendant pleading guilty, agreeing to the testimony given during pretrial investigations (read out in court), and waiving additional questions. This is essentially a plea bargain during the trial phase. The supposed incentive is the promise of a swift exchange, which is why Russian authorities strongly encourage Ukrainian prisoners not to prolong the process.

This was also the case with Oleksandr Maksymchuk. He initially agreed to the charges and requested a special procedure trial at the investigation stage. However, in court, the prisoner of war declared his protest. Discussions with the prosecutor, who was taken aback and argued, “You wanted to go home, think it over,” failed to persuade Oleksandr. Instead, the Azov fighter found a lawyer through his cellmates and requested to represent him pro bono. He knew a lawyer could not reject an individual request for representation, even in the Russian Federation.

“I have been in the detention facility for two and a half years. I have become so accustomed to it that I can’t even imagine what it’s like to be a free person or walk down the street. I don’t know what people do. What it’s like to have a phone, a laptop, a home, a dog, a family. So, I don’t really have much to lose,” Maksymchuk declared on December 5.

Legal Assessment

Andrii Yakovliev, a lawyer, managing partner at the law firm “Umbrella,” and an expert on International Humanitarian Law with the Media Initiative for Human Rights, highlights that Russian authorities have altered the interpretation of “terrorist activity” to expedite the sentencing of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Their accusations now concern not acts of committing terrorist activities but rather the arbitrary inclusion of organizations in the list of banned entities—organizations that, under the laws and customs of war, have the right to participate in hostilities as part of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

“We see a situation where, completely detached from the laws of war, a person’s affiliation with a particular unit of the Ukrainian Armed Forces is interpreted by Russia as participation in terrorist activities. They only need a decision by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation to include a particular unit in the list of terrorist organizations,” Yakovliev emphasizes. “This is exactly how the Separate Special Operations Detachment “Azov” of the 3057 Military Unit of the National Guard of Ukraine, like other Ukrainian Armed Forces units, ended up on this list. In other words, Russia considers the participation of many Ukrainian units in the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ defensive operations as involvement in terrorist activities. And this is nonsense.”

After Russia included “Azov” in the list of terrorist organizations, the conviction of the brigade’s personnel under this accusation became inevitable.

However, from the perspective of International Criminal Law, such trials are illegal and constitute war crimes, as prisoners of war are not only convicted for participating in combat, which is prohibited. They are also deprived of their right to a fair trial.

“The inhuman conditions of detention and constant torture leave prisoners with no choice but to incriminate themselves, hoping to alleviate their suffering,” Andrii Yakovliev adds. “Such testimonies cannot be regarded as evidence. Russian courts are so dependent on the authorities, so disregard internationally accepted principles of justice that the trials and their verdicts have nothing to do with justice. Moreover, they are likely to worsen the fate of prisoners of war. These verdicts cannot be appealed: all the accused and their lawyers can achieve is a slight mitigation in detention conditions.”

The expert also points out other glaring flaws in the trials of Azov fighters in Russia. One of the key issues is the testimony of witnesses presented by the prosecution. They only say what the prosecution wants to hear; they are not summoned to court, and their statements are only read aloud. Moreover, they are not actual testimonies but rather protocols written by investigators. These trials also exclude public observers, and defense lawyers effectively act as prosecutors.

“Defendants often refuse to testify in court as well. Add to this the other violations, and you’ll understand why judges are so quick to deliver verdicts favorable to the prosecution. In such courts, there is no real examination of the prosecution’s case. All participants know the outcome in advance, and the process becomes a farce where only punishment is real,” lawyer Andrii Yakovliev concludes.

Andrii Yakovliev, an expert on International Humanitarian Law

“Sasha took such a desperate step because this is a fight for justice. That’s just how he is,” Nataliia, Maksymchuk’s wife, explains. “Sasha lost his parents at the age of 14. He said he joined the army because he had no father’s example. He could gain courage and find someone to look up to only in the army. Sasha is a very committed and stubborn person. He defended Ukraine and left his family to save the country. What can he be judged for? He always believed his homeland would not turn its back on him.”

A few hours after the verdict was announced, Oleksandr Maksymchuk was transferred back to Taganrog. Neither his family nor his lawyer knows what is happening to him in this closed prison, as gaining access to this detention facility is impossible.

These days, the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don is hearing several cases involving Azov fighters who defended Mariupol. The Russian prosecution accuses them of “participation in a terrorist organization” (Part 2 of Article 205.4 of the CC of the Russian Federation) and “undergoing training to carry out terrorist activities” (Article 205.3 of the CC of the Russian Federation).

This publication was prepared with the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands.