Traces of War on Every Building: A Report from Sarajevo, Where War Criminals—Like Russia Today—Claimed That Murdered Children Were a Myth

The Bosnian War officially began on April 6, 1992, and lasted for four years. According to various estimates, around 100,000 people were killed during the conflict, with another 31,000 reported missing. Over 2 million people were displaced both within the country and beyond its borders. More than three decades have passed since then, yet most families have not returned to their homes. Around 8,000 missing persons are still being searched for to this day.

At the invitation of the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), a Ukrainian delegation consisting of representatives from civil society organizations, families of the missing, and government agencies visited Bosnia and Herzegovina to exchange experiences.

The Bloody History of One City

The plane is descending. Soon, it will land at the airport in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, surrounded by mountain slopes on all sides. From a bird’s-eye view, the mountains are breathtaking: winding roads and bodies of water, small houses nestled in lush greenery. Contemplating these stunning landscapes, it’s hard to imagine that just 30 years ago, these very mountains claimed thousands of lives. Today, numerous cemeteries, clearly visible from above, bear witness to the tragedy.

Sarajevo seen from the airplane window. Photo: Mariia Klymyk, MIHR

A walk through Sarajevo stirs a whirlwind of emotions. Though the war ended long ago, its aftermath remains visible on nearly every street. Traces of sniper bullets still scar building facades, and sidewalks torn apart by grenades preserve the memory of the dead. These craters, known as “Sarajevo Roses,” number in the hundreds across the city. Painted red, they mark spots where more than three people were killed during the siege.

Together with historian Nicolas Moll, we walk the streets where tourists now stroll freely. Children play on playgrounds next to residential buildings. However, 30 years ago, such a walk could have cost you your life—enemy snipers didn’t hesitate for a moment, even when a child appeared in their rifle scope.

Enemy bullets claimed the lives of nearly 1,500 children. We stop in the city’s central park, where a monument stands in their honor: two glass figures—one smaller, one larger—symbolizing the fragility of a child’s life and the heartbreaking reality that parents cannot always protect it.

Monument to the children killed during the war. Photo: Mariia Klymyk, MIHR

—These cylinders are engraved with the names of the children, and in parentheses, you can see the name of their father—as a way to confirm these children were real. Back then, just like Russia today, the perpetrators claimed the victims were a myth—that they never existed. — Nicolas Moll explains.

He adds that the parents of children killed during the siege of Sarajevo joined together to establish an association—and it was they who initiated the erection of the monument.

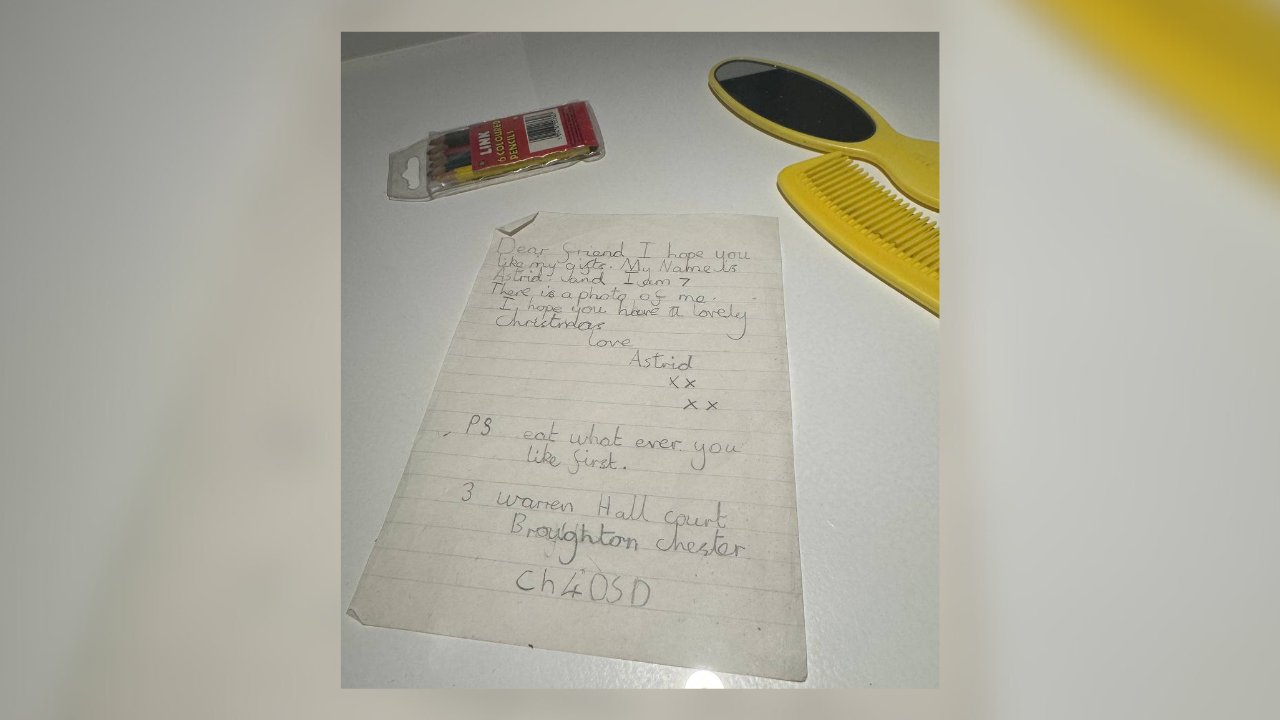

The War Childhood Museum also explores the theme of children during wartime, collecting testimonies from people who were children during the conflict. It’s a place where holding back tears is nearly impossible. The objects displayed inside glass cubes once belonged to murdered parents or siblings—handmade or found toys children played with while hiding in basements, the clothes they wore for the last time, and items that helped them survive. Each object carries either a joyful memory or a tragedy. The exhibition is dedicated not only to stories from the Bosnian War but also to other conflicts, including the war in Ukraine.

Exhibition at the War Childhood Museum. Photo: Maria Klymyk, MIHR

Searching for the Missing and Challenges of Identification

In 1995, at the initiative of the United Kingdom and the United States, the presidents of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia signed the Dayton Accords.

—Only after the peace agreement was signed did we realize how many people were missing, — Matthew Holliday, Director of European Programs at the ICMP, notes during a meeting with the Ukrainian delegation.

The decision to establish the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) was made in 1996 at the G7 summit in Lyon. This intergovernmental organization was tasked with addressing cases of people missing resulting from armed conflicts, human rights violations, or natural disasters. Although headquartered in Sarajevo, the Commission’s work extended across all former conflict zones in the Western Balkans.

The search proved to be challenging and lengthy. It was revealed that those considered missing or captured and held in concentration camps had been executed. To conceal their actions, the perpetrators dug up mass graves. They transported the bodies to remote locations in forests and mountains.

—Entire families disappeared, so there was no one left to file a report, provide DNA samples, or identify the remains. There were no witnesses who could point to burial sites or where to search for the bodies. However, some communities possessed at least some information and were willing to assist.—Samira Krehić, head of the Western Balkans Program at ICMP, shares her experience.

Samira Krehić (second right), head of the Western Balkans Program at ICMP. Photo: ICMP

The woman adds that there were cases when a family had only a birth certificate of their relative — the only proof that this person had ever existed.

Experts were involved in the search and exhumation of mass graves: forensic anthropologists, forensic archaeologists, entomologists, odontologists, and others. In the late 1990s, DNA analysis was not used as widely as it is today, so the first identifications of remains were carried out based on anatomical features, personal belongings, or documents. This method often led to mistakes, and families ended up burying someone else’s remains.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country to adopt a law on missing persons. On the initiative of the ICMP, it also established the Missing Persons Institute, which completely transformed the system for working with families and identifying remains.

However, not all problems were resolved. Due to numerous reburials, the bodies of the deceased often decomposed into fragments and ended up in different graves. As a result, families, having received only partial remains, refused to claim them for burial.

—Mothers waited until all fragments of their children were found. Time passed, and eventually, they accepted what had been identified and buried it. But their pain never went away because years later, researchers would knock on their door again, saying they had found new remains.—Amor Mašović, former head of the Institute for Missing Persons, explains.

The memorial cemetery in Srebrenica, where a mass genocide of Muslims took place during the war. Photo: Maria Klymyk, MIHR

Currently, approximately two thousand remains have not yet been identified. They are either in poor condition, or none of their close relatives have filed a search request or submitted DNA samples. Even now, over 30 years after the Bosnian War, the ICMP continues to receive reports of missing persons.

All That Will Remain Is Memory

Our car races along a winding road surrounded by mountain peaks. The incredible view takes our breath away—but for the locals, these landscapes are a haunting reminder of death. We are heading to the small town of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1995, one of the worst international crimes since World War II was committed there.

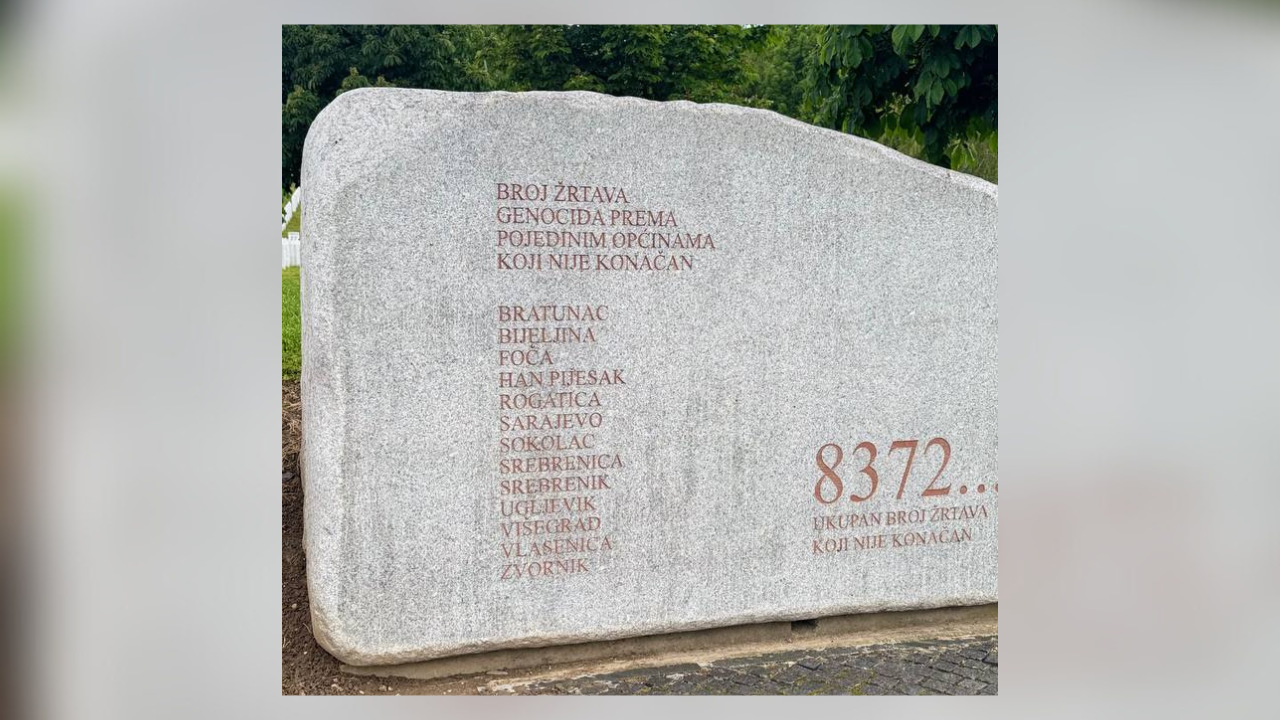

In 1993, the UN Security Council passed a resolution designating Srebrenica and its surrounding areas as a safe zone. However, in 1995, this very area turned into a trap for thousands of civilians. During several days in July, more than eight thousand Bosnian Muslims were killed there. In 2007, the International Court of Justice recognized the mass killings in Srebrenica as genocide.

Memorial plaque displaying the number of victims of the Srebrenica genocide. Photo: Maria Klymyk, MIHR

—Genocide is carried out according to a plan, and proving that is extremely difficult. That’s why the perpetrators of the mass killings in Srebrenica were convicted not of genocide but of crimes against humanity—because they were allegedly unaware of the broader plan. —Tarik Crnkić, prosecutor at the Special Department for War Crimes of the Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina, explains.

At the same time, he believes that those involved in the capture and transfer of prisoners, as well as those who abused them and participated in executions, are accomplices to genocide, as they realized the ultimate consequences of their actions.

In Srebrenica, we visit the Memorial and Cemetery for the victims of the 1995 genocide, which was opened in 2003. Despite the horrific memories, the victims’ families insisted that the memorial complex be established precisely at the site of the crime as a permanent reminder of what was done.

—Your war is still ongoing, but you already need to think about preserving memory, about memorial complexes. — Women from the association “Movement of Mothers of Srebrenica and Žepa Enclaves” call on addressing Ukrainian families. — It is a challenging and politicized process. We fought to the very end to ensure that this cemetery and this complex were exactly as we wanted and in the place we chose.

The Ukrainian delegation and the mothers who lost their children during the genocide in Srebrenica. Photo: ICMP

The war took away these women’s families, so they have dedicated over 30 years of their lives to searching for their loved ones. United into a large community, they still continue to fight for justice.

— If it weren’t for our efforts and persistence, we wouldn’t have achieved recognition of the genocide or any of what we have now. — The women admit. — So you must be strong and fight together for what you desire.

This publication appeared due to financial support from the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), funded by the Government of Canada. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They should not be attributed to the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), its donors, or its participating states.