They carved the “Z” on their cheeks, starved and tortured them to death: how Ukrainian captives are being exterminated in the Tula colony

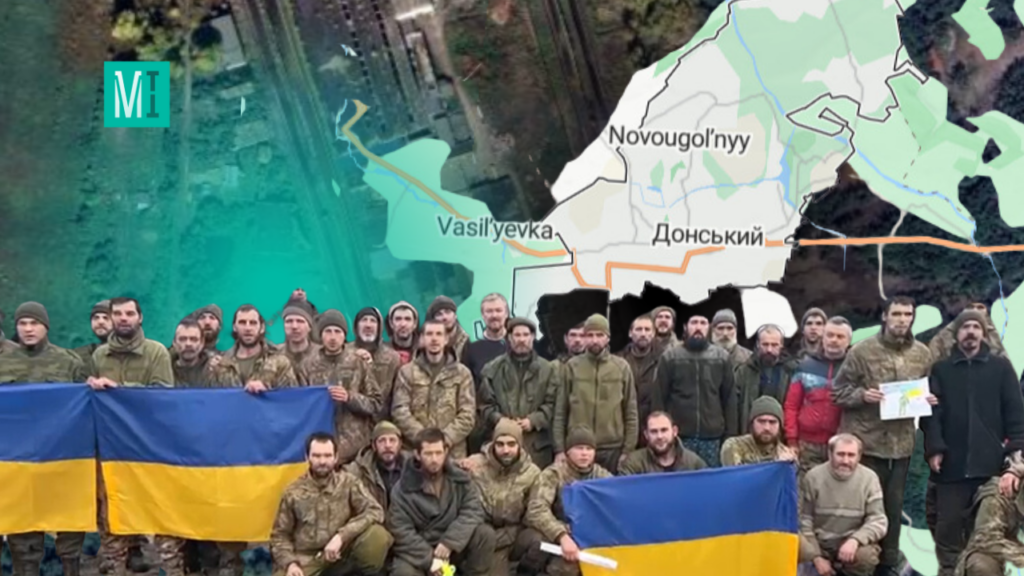

One of the most brutal Russian colonies, where Ukrainian military prisoners and civilians are held, is located in the town of Donskoy in the Tula region. MIHR has documented testimonies of several victims who were continuously beaten, tortured, and driven to insanity there. Their accounts serve as crucial evidence of the war crimes perpetrated by Russia. We have also identified possible individuals complicit in the torture and murder of Ukrainian military prisoners in this colony.

“It was on 5 May. The chief or deputy of the pre-trial detention center came into our cell in Kursk and said, “Well, khokhols, are you ready to go to Siberia to chop wood?” He called out surnames and sent us with our belongings for departure. They searched us, changed clothes, put into police vehicles, and drove away. As it turned out later, to the airfield. Our eyes and hands were tied up. We flew for what felt like a long time — about one and a half to two hours, then we rode in the police vehicles for about six more hours. At first, the road was good, then — the bad one. We thought we had ended up in some gray area and hoped that soon, on 9 May, we would be exchanged, but it didn’t happen — they brought us somewhere. We saw documents being handed over, dogs barking, and a man in a blue uniform getting into the van, and we realized it was a new stage. That’s how we ended up in Donskoy,” Ivan, a former Ukrainian prisoner of war and marine, recounts MIHR. He was captured in the Kherson region in March 2022.

Located in Donskoy, Penalty Colony No. 1 of the Tula region became the fifth place of detention for the young man; however, for a long time, he believed he was serving his sentence in Siberia.

“When I was later brought to the investigator, he asked, ‘Do you know where you are?’ I replied that I might be in Siberia. He laughed, ‘Let it be so.’ I guess they wanted to disguise the location. But we could read on the labels of pillows, soap, and toothpaste packaging: Tula region. Only in October, when they brought in a new prisoner, we learned we stayed in Donskoy”.

The Russian town of Donskoy is less than 600 kilometers from Ukraine’s border. The colony where Ivan ended up has been operating since the mid-1950s on the premises of a local mine. One of the buildings to the left of the main entrance to the colony is equipped as a pre-trial detention center. Behind a four-meter fence, the violators of the regime from all the region’s correctional facilities are kept.

Men’s Maximum Security Penal Colony No. 1, the town of Donskoy, the Tula region

In May 2022, two and a half months after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainians were brought to the detention center for the first time. Ivan, a marine, arrived at the colony at the same time. The day before, the detention center was entirely freed from Russian prisoners. “We heard them being forced to sing the Russian anthem, but we had no access to the prisoners; they even had different guards,” one of the Russian convicts, who was transferred to Donskoy, wrote about the Ukrainian prisoners of war.

In addition to Ukrainian military personnel, this building also housed Ukrainian civilians who were abducted during the occupation, mainly from the Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy regions.

In the summer of 2023, MIHR published material about the horrific detention conditions in this colony, continuing to gather information. Currently, we have new testimonies about more severe violations and inhumane treatment of prisoners of war. For safety reasons and at the request of witnesses, we have changed the names of ex-captives whose stories we are recounting. Our goal is to draw attention to this horrific prison and urge representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross to attend the colony with a monitoring mission to put an end to the torture.

Admission

“It was three or four o’clock in the morning, still dark, when we were brought to the colony. We were delivered to the main entrance and, one by one, taken out of the vans. I saw the guards beating someone. There was a path ahead, and we had to run along it to the courtyard,” Ivan recalls.

That night, about two hundred Ukrainian citizens from different detention facilities were transferred to Donskoy. Oleksii, captured in the first month of the full-scale war in the Chernihiv region, was brought from Kursk along with Ivan. Also, there was Serhii, who had been apprehended in the Kyiv region and previously held in Detention Center No. 2 in Novozybkov, Bryansk region. They also brought prisoners of war from Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 2 in Stary Oskol, Belgorod region.

Overall, large groups of Ukrainian captives have been brought to Tula Colony No. 1 on multiple occasions. For instance, in May 2023, several dozen prisoners of war from Novozybkov were transferred here. They were settled in empty premises, apparently vacated the day before. Mykola was among them.

When the prisoners are brought to the colony, they are driven to the courtyards. Ivan recalls it was crowded there, with no room to sit or stand. The Russians would shout out the surnames of the captives, who would respond, and then the admission would begin. Ivan stood there waiting until morning, until sunrise. Around six o’clock, he heard the Russian anthem and local prisoners chanting during the morning exercise.

The marine and other captives were taken to the isolation ward in the colony area, where representatives of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia (FSIN of Russia) were waiting for them. The first person Ivan saw was a Special Forces officer.

“When you run, shout: ‘Glory to Russia!’” he ordered.

The admission was managed exclusively by Special Forces officers. The people whom the captives identified as the colony employees followed their instructions.

During the admission, the captives are asked for their surname, photographed, undressed, and forced to crouch down. Then, they receive a prison robe; they are not allowed to wear the uniform of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Ivan says that everything happened pretty quickly.

“I even thought that compared to Kursk, the admission was easier,” Ivan shares.

Another military captive, Oleksandr, who was also brought to Donskoy that day, counted about 200 newly arrived prisoners. By the time everyone was processed, it was already evening. Then they brought dinner to the cell: cabbage and a cutlet.

“We were surprised again that after Kursk, they brought us food — a good piece of bread, a fish cutlet. But that was just the first impression,” the ex-prisoner of war explains.

Oleksii found himself in the cell even later. For over eight hours, wounded and standing on one leg, he stayed in a cramped courtyard with about fifty other captives.

“We were called out in groups of three,” he recounts. “‘Are there any conscripts?’ someone from the guards shouted. In my courtyard, there were three of them. They stepped forward, and the ‘Z’ was immediately carved on their cheeks. I didn’t see how they did it, but the guys said it was done with a rusty nail. After that, they were recognized because of it, and no one touched them for several weeks. Well, they weren’t actually left alone — they would be beaten but not mutilated until one of them got ligaments torn in his knee. Then they started finishing him off, shouting, ‘What’s the difference? He can’t walk anyway”.

Admission’ is a common practice in Russian prisons. For Ukrainian prisoners, it is particularly harsh.

When Oleksii was brought into the cell, he habitually sat on the bed — in Kursk, the wounded were allowed to sit during the day. But then, the door suddenly swung open, and the guards burst into the room and shouted, “What the f*ck?! There was no order to sit! Stand up, hands up, and stand.”

The cell

“My cell was designed for six people. It didn’t seem too small. But there were 23 of us in it. In the cells designed for four, there were 14–16 people,” Ivan notes. “The next day, the guard on duty ordered us to tidy up the cell. They allowed us to sit on the bench. They would also force us to learn Russian songs. But we had already learned them in Kursk. They brought new ones. We were supposed to sing them right in the cell.”

Ukrainian captives were placed in a separate facility isolated from Russian prisoners in the remand center.

On the third day of their stay in the cells, the captives were forbidden to sit — they had to stand all day. They were only allowed to sleep at night. They were fed on boiled cabbage mixed with some fat for several weeks.

“They called it shchi,” explains the marine.

Over time, they began to give us lean food. The soup had no potatoes — just murky water as if they rinsed the pot after cooking rice.

“If in the first few days, we could ask for additional portions, then later, such requests would result in battering. We really started to starve,” Ivan recalls.

There was no drinking water — rusty water flowed from the tap. The captives collected it in a plastic container, waited for the rust to settle, and only then drank it. Due to the lack of nutritious food, vitamins, and poor-quality water, many prisoners’ teeth started deteriorating. In the prison cell, there was no daylight, as the only window was boarded up. Instead, artificial lighting was kept on around the clock.

“In our cell, there were military personnel almost all the time. Only at the beginning of our stay, an elderly civilian man was placed with us. His right side was paralyzed, possibly due to a stroke. He had memory problems — he had forgotten his name and the year of birth. We couldn’t help him. Every night, he would urinate on himself. The stench was terrible — we couldn’t open the window or do the washing,” recounts the detainee. “I guess they were deliberately provoking us to argue over that man. We asked them to help him, but they did not respond. So we tried to cope by reducing the amount of liquid he could drink. We gave him tea in the morning, a little compote at lunch, and nothing to drink in the evening. There were no concessions for the old and sick person from the guards: they forced him to do everything the same way as us, and they beat him the same way,” Ivan shares his experience.

Ex-prisoners of war testify that the Russians sought to disorient those they held captive. They exerted psychological pressure on them by concealing their location, blurring the boundaries of the day due to the lack of daylight, loudly playing news from several months ago — good news for Russians and bad news for Ukrainians, suggesting that Ukraine had already surrendered and that Russia had significant victories on the frontline.

“In our cell, three guys had tattoos. One guy had ‘Save and Protect’ on his back tattooed in Russian. Another guy had ‘For the VDV’ [For Airborne Forces] on his arm because he used to serve in the paratroopers. And the third one had the ‘Rammstein’ symbol. They harassed the paratrooper and forced him to remove it. They gave him two days. Before us, there were prisoners in the cell, and they left small, sharp blades. So he used them to cut the tattoo off until it bled,” recollects the ex-prisoner of war.

The captives were forced to remove their tattoos using makeshift tools.

Ukrainian military in Donskoy were escorted to the bathhouse for washing and haircutting. Everyone who recalls how that happened says that for most of them, those procedures turned into torture. They were escorted and haircut by Russian prisoners, who, in addition, would clean and distribute food.

“They took me ‘for a haircut.’ They ordered me to stand up straight, close my eyes, and stand facing the ‘barber.’ He asked, ‘Have you tasted a Kyiv candy?’ I said yes. He replied, ‘No, not that one. Have you tried ours?’ And then he punched me in the Adam’s apple. I fell over, couldn’t breathe, and started coughing. Then I heard him say, ‘You need to drink after it.’ And he hit me in the face again. I fell down, and they didn’t touch me after that. That’s how the ‘haircut’ went. It was September 2022,” recalls Ivan.

The Ukrainian military and civilians interviewed by the MIHR unanimously agree: they were treated not as prisoners of war but as prisoners who were subjected to inhuman treatment by the Russian Federation: they were kept in confinement cells, restricted in everything, beaten, and humiliated. Neither the colony administration nor external visitors, such as investigators or prosecutors, attempted to stop those practices. Inhuman treatment and torture of Ukrainian captives have become a regular practice in the colony, having acquired distinct signs of consistency.

Systemic torture

As in other places of detention of prisoners of war on the territory of the Russian Federation, the guards in the remand center changed. In Donskoy, the rotation occurred on the twentieth of each month. The guards came from different regions. No one introduced themselves, but Ukrainians could distinguish them by their appearance and accent, and often, newcomers would reveal what city they came from. There were Siberians, Tuvans, and Dagestanis.

The attire of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia personnel is standard. The seconded Special Forces personnel mostly wore black or blue uniforms.

The first shift the newly arrived captives encountered was from Ivanovo. For the security of the prisoners, the Russians used the ‘BARS,’ a Special Forces unit of the Federal Penitentiary Service from Volgograd.

“While in May and June, we sang songs and did push-ups, in July, when the guards from Siberia arrived, real trials began,” recalls the ex-prisoner of war Ivan. “I remember how one of them came up with the idea that during the inspection, before taking us for a walk, we should close our eyes. And at that time, they would beat us, even on the head.”

The man recounts that the guards had large-diameter polypropylene sticks, “When they hit with them, there were marks on the arms and legs, but they didn’t break bones.”

Later, they began to ‘train’ the military, as they said, forcing them to perform excessive physical exercises. For example, they had to do 300 squats every hour. So, in a day, they could do 2500-3000 squats.

“In August, people of Asian appearance arrived. They beat the legs so hard that I got a lump on one of mine the size of a fist,” shares Oleksii. “I asked to see the nurse, but she looked and said, “Do more exercise; make your blood flowing.” After that, they stopped hitting my leg and focused on other parts. Some guys’ legs started to rot from that battering. In fact, three fingers could be put in the legs — such were the holes. They were not treated. They started beating us on the buttocks — one guy from the cell had it almost black with bruises.”

Oleksiy says that the prisoners were beaten around the clock. They could only take a break during the guards’ lunchtime. However, they quickly returned, and everything continued over and over again.

“No one got lazy, burned out, or bored. Sometimes, they would beat one person or several at once. In the cell, in the corridors, while escorting us for a walk, during walks,” the Ukrainian military testifies.

The inmates were taken for a walk in particular courtyards, where individual cells featured sturdy metal doors and a grate overhead. Positioned above was a platform where guards maintained surveillance.

“In the courtyard, we were supposed to move in a circle with our hands behind our backs and our heads lowered,” a military man, Mykola, recalls. “Most often, masked guards would rush in at that moment and start beating us. Those from Siberia were particularly brutal at such moments. They would throw some of us on the floor and beat them or push others against the wall. I barely avoided losing my front teeth there.”

“And they would test the strength of my head during the walk,” Oleksii adds to tell about the walk. “They would hit me in the forehead so hard that the back of my head hit the wall.”

“Then they would order us to stand up, sing, and rush to the cell. While we were running, they would hit us, delivering final blows with their fists. Back in the cell, we had to run in and shout, ‘Thank you, Chief, for the walk,’” Ivan recounts. “I remember a local youngster bragging about purchasing a large stun gun. He liked hiding where he could not be seen. We would run heads down, and he would zap us in the legs with the stun gun. And if we didn’t get our bearings, we would fall.”

As the witnesses testify, the most severe abuse was inflicted on the marines captured in Mariupol. It was in captivity where some of them suffered harsh injuries.

“For some reason, they considered the Marines special criminals. Next to my cell, there was a confinement cell where a captive from Mariupol was held. As soon as he heard his name, he would beg them not to beat him. But he would be forced to go out into the corridor, where they would begin to batter him with sticks and a stun gun. And not just a few times — we could hear screams for an hour. And that occurred several times a day,” recollects Oleksii.

He recounts that captives were also subjected to torture with electric shock using a TA field telephone, commonly known as a ‘tapik’ in local slang. They connected wires to it and the tortured victim and turned on an electric current. The Russians kept the ‘tapik’ in the basement. After the exchange, doctors found electric shock burns on Oleksii’s body, which he hadn’t noticed because his entire body was constantly covered in bruises.

During the day, the captives were forbidden from sitting, so they had to stand. As a result, everyone had swollen legs.

Prisoners of war were also tortured psychologically. Each new shift in the colony tried to come up with something new for this purpose.

“Someone would knock on the door with a stick or their fists — that meant we had to say, ‘Thank you, Chief,’ and after that, the captive on duty in the cell had to report. If they knocked twice, we would shout, ‘Yogurt Danone.’ Three times — we had to squat. Four —to say, ‘Pika-Pikachu.’ Five times — we had to respond, ‘Zelenskii, Biden, Bandera are faggots.’ Six — ‘Who doesn’t jump is a Moskal, and who jumps is a faggot.’ On the seventh knock — ‘Russia is a generous soul.’ And so on,” Ivan reports about the guards’ entertainment. If the prisoners made a mistake, they were beaten. The Ukrainian soldiers, released from captivity on 3 January 2024, explain that these practices still remain popular among the guards of the Donskoy colony.

“To give you an idea of how brutally we were beaten, let me put it this way: we had become so accustomed to beatings that we were no longer afraid of it but rather of the very anticipation of this moment. When you hear someone being senselessly killed in the corridor and realize that your turn is coming soon. That moment scared us the most,” recalls another ex-captive.

The guards even treated the letters the prisoners were encouraged to write home with mockery. It was forbidden to indicate where and in what condition a person was. They were only allowed to write general phrases, saying everything was fine.

“Later, the guards would collect those letters, sit, read them, and laugh. Meanwhile, we stood in our cells, heads lowered, unable to move,” the marine recalls. None of those letters ever made it to Ukraine.

On the eve of the exchange, Oleksandr was summoned for interrogation. The man didn’t know who that person was but assumed it was someone from the organization involved in the swap.

“He asked me, ‘Do they beat you?’ I looked at him, not knowing what to say. I replied no, and he said, ‘But why? Can’t I see it?’ Then he continued, ‘We came here being sure there was nobody here,’” the ex-detainee recounts, describing the conversation.

As he explains, in November 2022, the colony was inspected. The witnesses are unsure whether they were representatives of the Red Cross. However, after that, the prisoners were fed better. The beatings didn’t stop, but the mockery was not as intense. Those with open wounds were prohibited from going on walks to prevent reinfection. But the guards didn’t care.

“They enter the cell, and I tell them that my feet are festering and swollen, and the boots they have given me are too small, so I can’t put them on. I ask for other boots and remind them that taking such sick people out is prohibited. But the guard says, ‘Damn it, wear your slippers.’ I would wash my wounds with urine and apply toothpaste to them so they started to heal. However, when I went for a walk, all the wounds started rotting again,” Oleksandr explains.

At the next stage, the torture in the colony intensified. This was reported to MIHR by those detained there in May 2023.

Death in captivity

The condition of the prisoners of war deteriorated due to constant abuse. They say that in ordinary life, one would never have thought the human body could endure such physical and psychological stress. However, not everyone could withstand it.

“Once, several guards took one of the prisoners to the courtyard and beat him there. Then they returned him to the cell. In the evening, he felt unwell and asked for a pill; he was given validolum. We were woken up at night again, but he couldn’t get up. Then, an ambulance arrived. In the morning, when the new shift of guards came in, I heard they failed to resuscitate him — he died from сardiac arrest,” Ivan shares his memories of the events of the summer of 2022.

Oleksii also talks about deaths in captivity:

“I heard the body being dragged out of the cell by the legs. We all heard it. But we know nothing about who it was or the cause of death.”

After such incidents, ex-prisoners of war say, the person in charge of the zone would come and investigate the circumstances.

“Then they would weaken the regime in the cells for a while, even allowing us to sit on the beds during the day for an hour. I remember it was like that in December 2022. But it didn’t make much difference to us,” recounts the ex-captive.

He and others recall that sometimes people were taken out of their cells unconscious after battering.

“One night, when we were already used to being awakened, a man with a stroke in our cell couldn’t get up. He just lay there staring. The guard asked why he was lying down. We explained that something had happened to him and that he needed a doctor because he was unresponsive. They came in, looked at him, and said the doctor would only come in the morning, although we knew there were doctors on duty there even at night. But they didn’t call anyone. That was the first time they woke us up that night. During the second time, they didn’t bother our cell and went to others. In the morning, we started to lift the man, but he didn’t respond anymore. A new shift came, composed of locals, who called a nurse, and she administered an injection to him. Afterward, the ambulance took the man away, and we never saw him again,” Ivan shares his experience.

MIHR is also aware of a case of death after captivity. A civilian who was returned as part of an official exchange died a few months after his release. His relatives told us that he had been held in the colony in Donskoy but was reluctant to talk about what he had gone through.

Confinement cell

There are three confinement cells on the first floor of the pre-trial detention center in the Donskoy colony. Oleksii spent 108 days in one of them. He says he lost hope of getting out of there alive. Before him, a marine had been held in that cell, and he had left prayers and farewell messages to his family on the walls. Oleksii describes the cell as an unsuitable place to stay: the sewage pipe was leaking, mold was everywhere, and water was dripping from the wall.

“All the feces were flowing into my cell. The water dripping all the time and the surveillance camera’s microphone crackling drove me crazy.”

The conditions in the confinement cells at the Donskoy colony are unfit for living; however, many captives were held there for over 100 days. The photo is illustrative.

Those held in the confinement cells received a limited amount of food. They were given only two spoons of porridge and a piece of bread.

“Sometimes I didn’t have the power to chew that bread,” Oleksii adds.

Ex-prisoners of war, released at different times, recount that the guards at this pre-trial detention center continuously interrupted the sleep of the captives.

“In the middle of the night, they suddenly turned on the lights. I thought it was morning already; they would shout, ‘Wake up!’ We would jump up, not understanding what was happening. They would order us to stand. At first, we would stand for half an hour; then, they would give us a break. But within an hour or so, they would wake us up again. And since it was already morning, sleeping was forbidden. Eventually, we not just stood, but also squatted during the night,” the ex-prisoner of war Ivan recounts.

In the confinement sell, the captives’ sleep was disturbed more frequently, for extended durations, and with heightened physical exertion. While inmates might squat 300 times in their regular cells, the punished captives were expected to squat 500 times.

Some were deprived of sleep for several days.

An ex-prisoner of war shares his memories about one of the cells where he was held that was opposite the confinement cell:

“I remember once a marine from Mariupol was thrown into it. He was constantly beaten there, and they said that his legs were already black, so he would have to use a wheelchair. He was forbidden to sleep at night. In total, he did not sleep for about seven nights. After the battering, they would bring him to. The further fate of the marine is unknown. Others were also ‘rocked’ there. A guy had a record of 13 days without sleep. I don’t remember his last name, but at night, they would wake him up and beat him. If he would doze off, he would stand for 13 days straight. He already started hallucinating. I don’t know what they demanded from him. But he said, ‘Let me sign it.’ They rubbed their hands together, satisfied that they had achieved their goal.”

“In such conditions, I was considering suicide because there was nothing left of you there anyway,” Oleksii explains. “You are always forbidden to do anything. They give you food, but you have a minute to eat it. And within that time, you also have to wash and return the dishes. There are no rags, no soap or toothpaste. In the cell, they gave out a tube of toothpaste a couple of times, only 30 grams, expired 12 years ago. I ate it — I was so starving! Constant searches, 5-6 times a day. Constant psychological pressure and lack of medical help. My leg is festering. It hurts. I start rubbing my leg on a rusty nail to clean that pus. The floor is covered in feces. I’m afraid of getting another infection. And instead of calling a doctor or giving me some antiseptic, they take me out into the corridor and start beating me, saying, ‘There was no order, let it rot!’”

Interrogations

The prisoners of war share their experiences about interrogations in the colony. Some were interrogated only at the beginning of their captivity, while others were questioned throughout their detention.

“There were investigators and prosecutors. I was interrogated by prosecutors. They asked about my personal life and took fingerprints and DNA samples. It’s necessary for them. They compared it with the testimonies that I gave in Kursk. Many guys were not precise enough, so they were taken in for interrogations again and again,” Ivan reports.

Serhii, who was captured in the Kyiv region, recalls being interrogated by representatives of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation (ICRF). Usually, he says, they wore civilian clothing.

“The day before interrogations conducted by prosecutors or local authorities, we were ‘prepared.’ Special Forces would come in, beat us, and explain how to behave during interrogations. But when representatives of the ICRF arrived, there was no battering. They might have had a certain influence on the colony administration.”

Once, Oleksandr overheard a conversation among the guards as they stood in the corridor, marveling at the permissiveness in Tula Colony No. 1.

Someone from the new shift was conversing with someone from the old. “We’ve been to various detention facilities, and in some, you can’t lay a finger on them; in others, you can do very little, but here, you can do whatever you want.” The newcomers were astonished at how ruthlessly they were permitted to treat us,” Oleksandr recounts.

The man adds that during interrogations, the captives were subjected to 3D facial scanning. They were warned, saying, “If you end up being on Russian territory again and detained, they won’t treat you ‘so leniently’ anymore.”

Who ordered the torture

Mariia Kvitsinska, an expert at the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) in Europe and Central Asia, reminds us that according to international humanitarian law, prisoners of war are protected persons and should be held in special camps separately from Russian prisoners or civilian detainees. The conditions in these camps must be no worse than those for Russian army soldiers and adhere to definite standards in terms of detention facilities, food, clothing, hygiene, medical care, dignified treatment, etc.

Mariia Kvitsinska, an expert at the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) in Europe and Central Asia

“In this case, there is not a single standard that Russia has not violated,” Mrs. Kvitsinska explains. “Numerous cases of torture of ordinary Russian prisoners, especially during prison rituals, have been documented in various places of detention in Russia.”

“For instance, if prisoners of war or civilian detainees have not directly encountered the leaders of institutions but have experienced consistent torture across various detention sites, torment is probably either instigated by a particular leader or sanctioned by higher-ranking officials.

Torture constitutes both a war crime and a violation of human rights. Instances of torture fall under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, the UN Committee Against Torture, and the International Court of Justice. Moreover, in a European country, such as Germany, where legislation on universal jurisdiction applies, a victim can seek assistance from the law enforcement authorities of that nation if they need it.”

Potential perpetrators of torture and murder

The Penal Colony No. 1 in Donetsk is usually mentioned in connection with torture. For instance, in 2012, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) recognized the justified complaints of Vitalii Buntov (No.27026/10 ‘Buntov v. Russia’). Buntov complained that he had been subjected to torture and inhumane treatment in this Tula colony. During a scheduled visit on 4–5 February 2010, his mother, Tetiana Krakivska, a doctor by profession, witnessed her son’s condition firsthand and filed a detailed statement to the investigative authorities. His injuries, in particular, indicated oxygen starvation.

It should be noted that prisoners of war interviewed by MIHR say they were held in isolation and did not see or hear the leadership of the colony. Russians forced captives to close their eyes and bow their heads when meeting with representatives of the system.

MIHR has identified the surnames of the colony’s leadership, who are believed to be involved in the torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians.

At the time of the transfer of the first Ukrainian prisoners of war in May 2022, the institution was headed by Oleksandr Oleksandrovych Plaksin.

Oleksandr Plaksin was in charge of the colony in Donskoy in early 2022 and arrested in the fall of 2022

After Plaksin’s arrest, Kamo Heorhiiovych Habrelian headed the institution.

Kamo Heorhiiovych Habrelian is on the left. Next to him is Tetiana Larina, the Human Rights Ombudsman in the Tula region

Habrelian was returned to his former place of work — to run the penal colony No. 7 in Shchekino, the Tula region.

In early 2023, Colonel of the Internal Service Ivan Vasylovych Davydenko became the head of Penal Colony No. 1 in the Tula region. He was transferred from Penal Colony No. 6 in Novomoskovsk. Before that, he served as the deputy chief of Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 2 in the Altai region.

Ivan Vasylovych Davydenko was appointed to the position of the Head of PC No. 1 in Donskoy in early 2023

We also focus on Major General of the Internal Service of Russia, Ivan Prokopenko — the head of the Federal Penitentiary Service in the Tula region. He hails from Vinnytsia. According to the collected data, in 1993, after completing his military service, he worked as a junior inspector of the regime and security department of the pre-trial detention center No. 1 in Moscow, commonly known as Matrosskaya Tishina. He was awarded the Order of Courage. On 7 September 2019, he was appointed Head of the Federal Penitentiary Service in the Tula Region. In 2021, Prokopenko was ranked Major General of the Internal Service. Since November 2017, Ivan Prokopenko has been under sanctions from Canada. In 2022, he was sanctioned by the United Kingdom and Australia, and in 2023 — by Ukraine, the United States, and New Zealand. As the head of the Federal Penitentiary Service in Tula, Prokopenko is believed to be involved in or support the recruitment of prisoners for the Wagner Group.

The head of the Federal Penitentiary Service in the Tula region, Ivan Prokopenko, is under sanctions from six countries.

The prisoners also recall a woman who attended the detention center but did not enter the cells. Although they cannot describe her, they note that after her visits, the rules changed.

“Innovations appeared the very next day. For example, we started to be woken up at night, even though we would sleep through the night before. Initially, we were fed properly, but after her visits, the food became terrible — just water. Every time we heard her voice or knew that she had attended, something changed,” Oleksandr recounts.

As he notes, he knows neither the name nor surname of that woman. But it must be Nataliia Volodymyrivna Dromina, the head of the branch of the medical and sanitary unit No. 71 that serves PC No. 1. She is among the officials responsible for the regime in the colony, including providing medical assistance care. Dromina must ensure that no coercive measures are applied to the sick. She is also responsible for the quality of food.

The way home

The first prisoners for exchange from Donskoy were transported in December 2022 — over seven months after their detention in this colony had started.

Ivan recalls Borys, a two-meter-tall basketball player in their cell.

“He was on the verge of passing out, almost transparent. People in civilian clothes entered the cell and called out his last name. They chose one person from each cell. We asked where they were taking them. They replied, ‘To be shot.’ Another person added, ‘If everything goes well, you will be shot in a week.’

The exchange on 31 December 2022, captives from the colony in Donskoy among the released

The guy mentions hearing the rumble of vehicles on the street, possibly police vans, which later subsided. The basketball player must have been taken out of the colony, but no one knew where exactly. As subsequently found, the Ukrainians had been transported to Mordovia to Maximum Security Penal Colony No. 10 in the Zubovo-Polyansky district. In May 2023, the pre-trial detention center in the Donskoy colony area was emptied, after which a new batch of prisoners was brought there, including from Novozybkov in the Bryansk region.

Ivan, a marine who was exchanged earlier, in early 2023, recalls,

“I asked to keep my socks, as they did not give me new ones. ‘Take them — you can hang them in a frame at home,’ the guard replied. I was surprised — they were taking me to the firing squad.”

When Ivan was weighed in a military hospital in Ukraine after his capture, he weighed 49 kg. Before captivity, he weighed 63. Oleksii lost 40 kg during detention, and Serhii lost 15. Oleksandr lost 10 kg; he was slim even before the imprisonment, and the guards in Donskoy called him bony.

The basketball player Borys returned to the Ukraine-controlled territory only a year later, on 3 January 2024.

The Media Initiative for Human Rights has documented about 15 testimonies of prisoners of war and civilians held by the Russian Federation in PC No. 1 in Donskoy. These and other testimonies constitute significant evidence of war crimes committed by Russia.

We have approached the International Committee of the Red Cross to request a visit to Penal Colony No. 1 in the Tula Region of the Russian Federation to monitor the conditions of detention of Ukrainian citizens, both civilians and military personnel, as well as to clarify the circumstances of the deaths of those mentioned in this article.

The material was prepared with the participation of Olena Bielachkova, coordinator of groups of families of detainees.

The material was prepared with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework of the joint initiative ‘European Renaissance of Ukraine.’ The material represents the authors’ position and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or the International Renaissance Foundation.